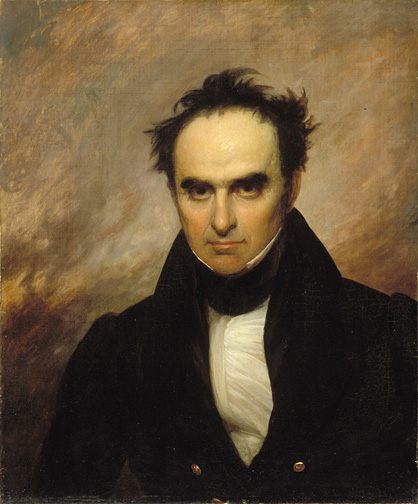

This year, August 9 marks the 180th anniversary of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. In 1842, the American and British governments, respectively represented by Daniel Webster and Alexander Baring, Baron Ashburton, resolved longstanding points of contention and established grounds for better relations in North America.

The first point of contention involved the still-unsettled boundary between Maine and New Brunswick. In the late eighteenth century, partly as an assertion of sovereignty, New Brunswick’s colonial government had issued land grants to Acadian and French-Canadian families on the Upper St. John River. This growing population belonged to a British colonial world much more than it did to the American Republic. The arrival of American entrepreneurs, who sought to impose their own political and economic structures, resulted in clashes with New Brunswick officials in the 1830s. Reprisals then led to an influx of British troops, to which the Americans responded in kind. By the end of 1839, a mounting military presence had halted the cycle of reprisals, but tensions had yet to subside.

Another area of conflict stemmed from the Canadian Rebellions. In the wake of their military defeat, in the fall of 1837, many insurgents sought refuge in the United States. They then used American soil as a springboard for invasions of Upper and Lower Canada. At times they did so while sympathetic U.S. officials turned a blind eye to their actions. Worried that the British would respond to these raids by entering American territory, President Martin Van Buren empowered federal officials to report and arrest the foreign agitators and sent troops to the border—to restrain the Canadian expatriates rather than to prepare to meet British regulars on the battlefield. In fact, the Upper Canadian militia did enter American territory to burn the ship Caroline, alleged to be supplying insurgents ahead of another cross-border raid. Van Buren weathered war cries from his own nation and spared the continent yet another Anglo-American conflict.[1]

The violation of sovereignty that occurred with the Caroline incident would be resolved in an exchange of notes between Webster and Ashburton. The latter offered regrets that could be construed as an apology. More broadly, the two diplomats’ correspondence reveal growing trust and esteem that could serve as the basis for amicable relations between the two great powers. This was borne out in the settlement of the northeastern boundary dispute in 1842 and subsequent military de-escalation along the border.

British officials chose restraint; Van Buren and Webster, a Democrat and a Whig, made it clear that peace with Britain was now in the United States’ national interest.

Historians will undoubtedly continue to debate the significance of the events of the early 1840s in making a North America we recognize today. In his work on the War of 1812, Alan Taylor invites greater attention to the Treaty of Ghent of 1814. Whereas officials on both sides had previously believed that one side must inevitably destroy the other in North America, the costly and fruitless conflict of 1812-1815 changed minds: peaceful coexistence, if not ideal, might be necessary. That war, still well within memory, no doubt played into the actions of policymakers from 1837 to 1842.

The theory of peaceful coexistence was put into practice with Webster and Ashburton. If their treaty was not a 180° shift from the Anglo-American relations of prior years, the hard work of ensuring long-term peace—at great political risk at home—cannot be diminished. When the saber-rattling campaign of James Polk, annexationism, and the controversies of the Civil War threatened to spark a new international conflagration, outstanding issues had at least been resolved and a precedent for positive relations had been set.

I conclude, in my “Choosing Peace and Order,” published in the International History Review,

Conventional wisdom had taken the deployment of British and US troops in the borderlands as an imminent threat to the other nation. It became clear, in this period, that a stronger military presence could in fact serve the cause of peaceful relations. Security required strong central state authority. In the United States, the neutrality law enrolled a number of government offices in surveillance and thus the nature of law enforcement changed . . . [I]n the absence of a border-security agency, US regulars assumed a peacetime role under direct presidential authority. Such assertions of sovereignty, their continuation through different administrations, and their ratification in formal treaty-making strengthened the border as a geopolitical and legal fact. A better definition of the responsibilities attendant to this fence’s upkeep would henceforth help Britain and the United States remain at peace with one another.

We could push the argument even further—as I have done in the Montreal Gazette. The path of peace was an essential prerequisite to the establishment of an autonomous Canada.

Webster-Ashburton’s importance is still with us while other landmark agreements between Britain, Canada, and the United States have faded from view. If nothing else, by illustrating the difficult yet always worthwhile pursuit of peace, the treaty remains an event very much worth studying and remembering.

[1] My focus on these two disputes reflects the blog’s purview. Still, we should not forget that Webster and Ashburton’s talks covered the fate of the Creole, an American slave ship that was successfully overtaken by its enslaved “passengers” and sailed to the British Bahamas. In Article IX of the final treaty, both countries agreed to redouble their efforts to end the international slave trade.

My ancestors were in Indian Stream and left for Compton