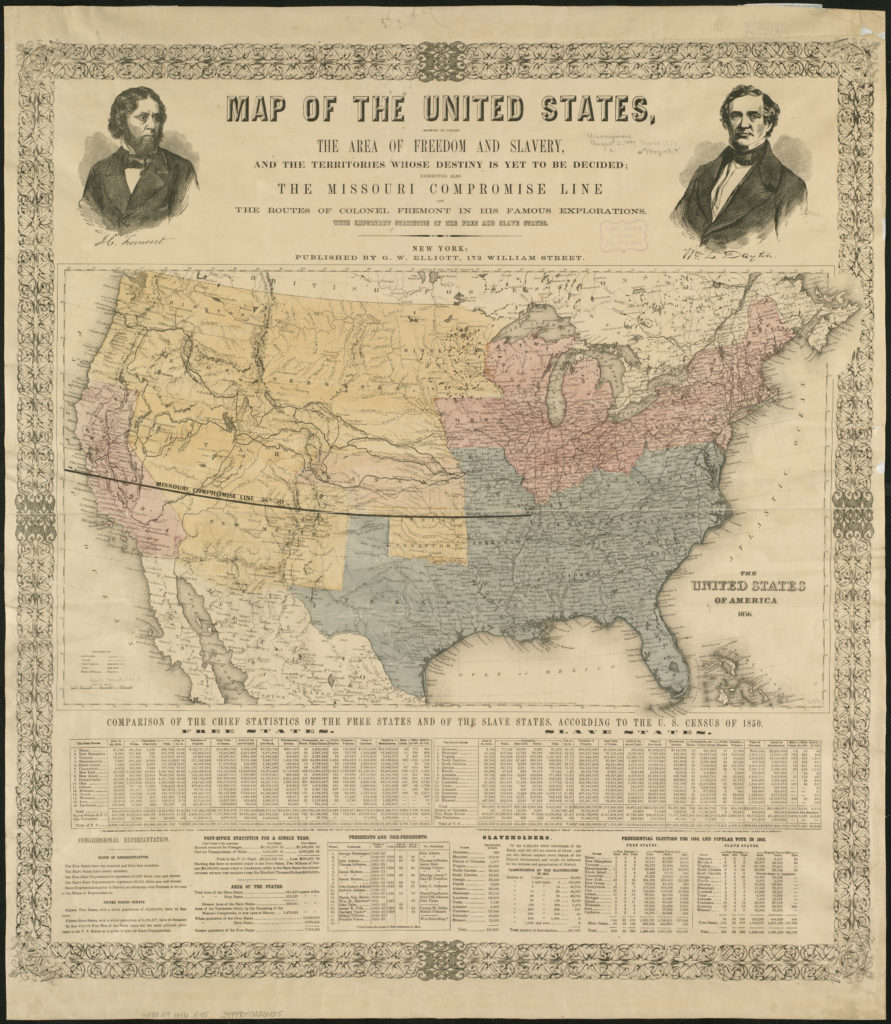

In his last few years in office, U.S. President John Tyler (1841-1845) devoted considerable attention to—and spent a great deal of political capital promoting—the annexation of Texas. The election of James Polk to the presidency on the same platform in November 1844 attested to the American public’s support for annexation and the Senate acted on the matter the following February. Before long, the United States would be at war with Mexico over border disputes and, as a result of its victory, the Great Republic would gain one million square kilometres of territory stretching to California.

But, in this age of “Manifest Destiny,” American expansionists were not merely looking covetously to the Southwest. Polk also pledged to defend U.S. interests in Oregon Territory, then under joint Anglo-American occupation. And, as Congress debated the Texas issue, some Senators happily weighed in on the wisdom of annexing British North America as well. The following excerpts of the Congressional Globe offer key arguments on the matter.

A. S. Porter, a Whig, presented the following petition from certain citizens of Detroit, Michigan, to the Senate on February 3, 1845:

We refer to the acquisition of Canada; an object, the importance of which did not fail to attract the attention of our forefathers, as attested by the Articles of Confederation. It would be useless to discuss the advantages of such an acquisition to the United States; they present themselves to every one in any degree acquainted with the geography and the commercial means of the country. None can be more sensible of these advantages, none, we are confident, will labor with more alacrity to secure them by all constitutional and peaceful means, than your honorable bodies. To give to the United States the control of the entire valley of the St. Lawrence, is to give them the undivided empire of the great lakes; to augment to an incalculable amount the commerce of the country; to remove forever the necessity of expenditures for fortifications on the Northern frontier; and to close, for all future time, the avenues of invasion from this quarter.

By no means would this annexation constitute an unfriendly measure:

A large portion of the population, especially of Upper Canada, have emigrated thither from the United States, and the friendship of the great mass of the people of Lower Canada for American institutions is well known.

The petitioners added that the annexation of Canada “would introduce into the Union a highly civilized, intelligent, and liberty-loving people” and would help to conserve the delicate balance between North and South, which Texas threatened to disturb. They also suggested that the U.S. administration open negotiations with Britain and perhaps offer to purchase Canada.

Senator E. H. Foster of Tennessee, also a Whig, objected to the proposal on constitutional grounds and rejected any alleged parallels between Texas and Canada.

It was evidently, he said, trifling with the pride of a friendly power, and that power one with which our existing relations were confessedly delicate and unsettled. Why provoke that pride . . . Why call upon the Senate to endorse the provocation by lending this memorial a respectful sanction, and giving it thereby an importance it never could otherwise obtain? There was certainly nothing in the complaints or the disquietude of the people of Canada; nothing in their political condition that he knew of or had any right to credit; no popular movement, no public manifestation, which could induce the wildest philanthropy to believe they would change their allegiance if they could.

Porter responded that the petition was much less about Canada than Texas. It was submitted in response to “a policy purely sectional” designed “for the security and protection of the peculiar institutions of the South.” To annex Canada, in short, was to stand for the rights and views of Northern states, ensuring that an enlarged South would not drown them.

Only a few years after the Patriot War, the senator from Michigan compared the Texan revolutionaries of 1835-1836 to the Canadians who had risen up in rebellion shortly thereafter. Whereas the U.S. administration had openly sympathized with the Texans, it had sought to disrupt and destroy the “Patriots” agitating along the northern boundary. American officials had responded to two near-identical situations in almost entirely opposite ways. But the double standard was unjustified. “It is, I repeat, sir, humiliating to find . . . that we have done wrong only because we could do it with impunity and right only because we dared not do otherwise,” Porter argued.

He stated, in conclusion, that “General Jackson [the former president] speaks of the annexation of Texas as indispensably necessary to guard us against the hostile approaches of England. Sir, is it necessary for me to point to the geographical position of these memorialists [Detroit] in order to show their exposure to such hostile approaches?”

A former Democratic governor of Alabama, A. P. Bagby, entered the debate. He suggested that the annexation of Canada, if taken seriously by the Senate, would “produce insubordination” in the British colonies. Would Porter truly be ready to help Canadian rebels overthrow their imperial masters? The Canadian question, Bagby declared to the Senate chamber, must be considered on its own terms, its situation being very different from that of Texas. In any event, “gentlemen” should speak plainly and fight the annexation of Texas directly, if opposed to it, rather than muddying the waters by introducing Canada into the debate.

Foster in turn claimed that the entire area north of the Missouri compromise line—apparently destined to be forever spared the “peculiar institution”—would in time form numerous free states counteracting the influence of an expanded South. Northerners had nothing to fear; indeed,

Already and long since powerless, the South asks nothing of the North but friendship, union, and the protection and preservation of her liberty and property under the solemn compromise of a common Constitution. For these blessings she pays a heavy, perhaps a dear tribute. She has paid it cheerfully, and may continue to do so until her cup of bitterness is made to overflow.

With a reflection on the merits of the Union and its “innumerable blessings,” but also some trepidation about the future, the discussion quickly concluded. The Senate voted “that the memorial be received and laid upon the table” alongside a similar petition submitted by D. S. Dickinson of New York, such that no further action was taken.

The brevity and unravelling of this debate as well as President Polk’s willingness to compromise with Britain on Oregon—the ultimate agreement was far from the infamous 54°40’ line—suggest that American discussions of Canada were about Canada only to a point, even if the Senate misconstrued the sincere desires of Detroit residents.

After 1846, Anglo-American relations thawed, but fears of an eventual American invasion remained. Such anxiety was palpable amid the many international controversies of the U.S. Civil War, with reason. But until then, “Canada” was very often a way of signalling ideological intents, a by-word for a certain vision of the United States, a political punch or counter-punch. “Canada” was in this regard not a territory, nor even a political regime, but an expression of domestic hopes and fears. We may wonder if that is not still the case amid new controversies in 2018.

Pingback: canada annex us - seekanswer