My earliest memories and only childhood memories of New York State are of peaks and valleys: a family trip to Whiteface Mountain and Ausable Chasm. Eventually I would see New York City, Jamestown, Little Falls, Troy, Whitehall, Ticonderoga… the list goes on (though Watkins Glen remains obstinately on the bucket list). Only recently did I discover a family story that offers precedents and speaks to a much larger past.

Almost exactly a century ago, in 1924, the Sherbrooke Daily Record reported that “Mr. and Mrs. Orin Lacroix, Mr. and Mrs. Fred Lacroix and son and Mrs. Edson Lacroix motored to Ticonderoga recently and spent a couple of days with relatives.” A sister of Mrs. Fred Lacroix (Alphonsine Domingue) had moved to Ticonderoga. There were at least two more Domingue sisters; they lived in the larger industrial cities of Springfield and Leominster, Massachusetts. This was typical. Countless Quebec families had close relatives across the border. There was something else, too. Migrants went to New England, but by no means were they confined to those six states. From Rouses Point to New York City via Ticonderoga, the Empire State was home to a sizeable French-Canadian population.

The area of New York that my great grandmother saw while Ol’ Edson was tending to the farm had little to do with la grande saignée as it is most commonly depicted. Ticonderoga was a small industrial hub. But Clinton and Essex counties were overall quite similar to the Lacroixs’ area of Quebec. Upstate New York must have seemed like a natural destination, just as natural as the movement of French Canadians from rural areas north of the border to rural areas south of the border.

These basic realities form the backdrop to my most recent scholarly article, “French-Canadian Settlement and Community Formation in Pre-Civil War New York State,” which appears in the latest issue of New York History. This article is a foray into a relatively unexplored field. Granted, some individuals have long sought to raise awareness of Franco-American history and culture in New York—including a small battalion of archivists, preservationists, and public history professionals across the state. The Samuel de Champlain History Center, for instance, shines by its manuscript and artifact collections. Scholars like Eloïse Brière have also done their part. Perhaps the most significant contribution yet as only just appeared. In Catholics across Borders: Canadian Immigrants in the North Country, Plattsburgh, New York, 1850-1950, historian Mark Richard (SUNY–Plattsburgh) draws attention to a key destination of French-Canadian immigrants during la grande saignée.

This book is particularly important for the light in sheds on regions where textile factories were not the economic foundation. Migrants to New York’s North Country availed themselves of much broader opportunities. Meanwhile, closer social intercourse and the influence of religious congregations led to Franco-Irish collaboration, such that in some respects, “religion trumped ethnic sentiment.” Franco-Americans in Plattsburgh and surrounding areas also mingled with Anglo-Saxons without surrendering their cultural traditions. The sheer proportion of people of French-Canadian descent in Clinton County dulled the harsher edges of nativism that were felt in parts of New England.

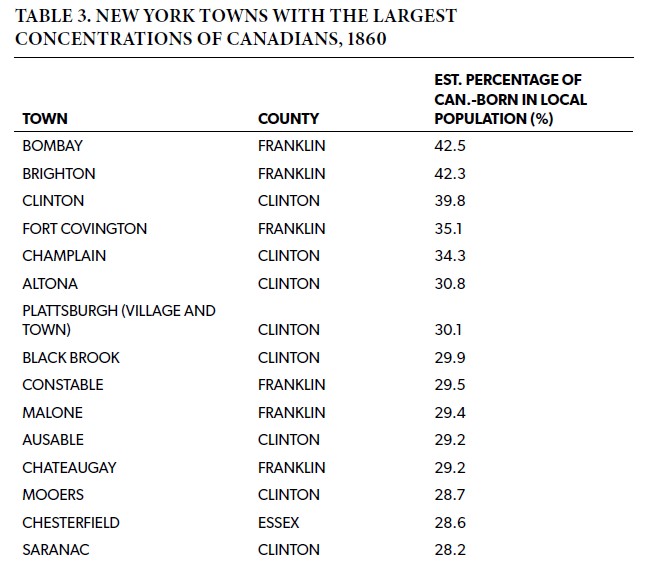

My article takes a different tack. It relies on systematic sampling of census records to draw a picture of the statewide presence of French Canadians in 1860, a valuable supplement to Ralph Vicero’s work on New England. As the editors put it, the article

demonstrates how mass-emigration from Quebec spurred significant institution-building and cultural development and shaped the economies of many upstate cities and towns. Lacroix’s essay simultaneously reorients the story of immigrant New York northward from Gotham and that of French-Canadian America westward from New England.

That is the big picture. At a less theoretical level, I explore French-Canadian destinations both from a numerical standpoint and through the tentative, difficult beginnings of common cultural institutions. New York was the state with the largest French-Canadian population in 1860. Migrants established churches, organized Saint-Jean-Baptiste celebrations, and took interest in politics. The challenges they faced anticipated those that awaited many New England communities following the Civil War—challenges that were often a function of the migrants’ limited means. Eventually, Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island exceeded New York’s Franco-American population. But in Clinton County and beyond, that population was still replenished by waves of newcomers. A distinct culture survived across generations.

There is much that has yet to be answered. We should hope for in-depth studies of the French-Canadian population of Franklin and St. Lawrence counties. There is undoubtedly much more to be known about more remote areas like Indian Lake, or lesser-known industrial communities like Waterford. And then there is New York City. To study Franco-America is by its very nature to de-center Ellis Island in immigration history. But the great metropolis is not to be neglected. The field of research will benefit greatly from a study of Canadian networks, institutions, and experiences in the city.

* * *

Just above Ausable Chasm, on the river, lies an old industrial hub, Keeseville, which actually sits astride not only the river but the towns of Chesterfield and Au Sable. On the eve of the Civil War, the combined French-Canadian population of those two towns nearly equaled Plattsburgh’s, making this one of the top destinations in the state. It is little wonder. A contemporary work underscored its industrial facilities: “2 extensive rolling mills, 3 nail factories, a machine shop, an ax and edge tool factory, a cupola furnace, and axletree factory, a horseshoe factory, a planing mill, 2 gristmills, and a nail keg factory.”

The region continues to attract outsiders, including Quebeckers who might be traveling to Lake Placid or Lake George—or turning off of the beaten path to explore lesser-known gems. Those who visit aim to spend rather than make money. A family trip in 1924 captured the gradual transition from one reality to the other. Deindustrialization and immigration policies have had their say, thereby perhaps sealing the fate of French-Canadian culture in northern New York, if not the entire Northeast.

But we would be fooled to think that an invisible past is an irrelevant past. We cannot understand New York State as it is today without the massive French-Canadian presence—particularly along the Upper Hudson River and in the North Country—that molded it economically, culturally, and politically. Thus, like other works in the field, this is an invitation to researchers in Franco-American history and immigration scholars alike.

For more on the politics of New York Franco-Americans, francophone readers may be interested in my book, “Tout nous serait possible” (Presses de l’Université Laval, 2021). I have developed other aspects of this French-Canadian history in journal articles, with more to come in an issue of Recherches sociographiques.

Otherwise, some of my questions and findings are available on this blog. On the settlement of Clinton County by Revolutionary War veterans and their families:

- The Canadians of Clinton County: The First Franco-Americans

- The First Franco-Americans Revisited: Revolutionaries and Refugees

- The Birthplace of Franco-America

On the French-Canadian presence in the central part of the state, see Part I and Part II of my community study of Cohoes.

For snippets of Franco-American history in other parts of the state:

- A Franco Media Mogul: Benjamin Lenthier

- New York State: Elements of Historical Geography

- A Canadian Excursion to New York City in 1851

- Migratory Beachheads and Marauding Canadians

In addition, I have reviewed a recent work that connects New York and Vermont, Franco-Americans in the Champlain Valley.

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - March 16, 2024 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

I am a descendant of Jane “Genevieve” Landry (of Constable, N.Y.), (1825-1913) who married James Frazeo/Frazeau (of St. Isidore) (1827-1908) 15 Oct 1849, Malone, Franklin County, New York, USAs (can’t find the church record). They moved from Constable to Pontiac Co., PQ, and eventually settled in Arnprior, Ontario. Witnesses: Philip Frazeo and Angelique Laundry. Philip Frazier (1824-1909) lived in Constable and married (1) Aurilla/Henriette Poirier (1833–1873); married (2) Delia Vanier (1842-1917). The Frazeau/Fregeau family goes back to the 1600’s in Quebec. Finally found that Jane (baptized 1826,St. Regis Roman Catholic Mission) is the daughter of John Baptiste Landry (2nd married to a Suzette) (listed in the 1840, 1850 Census in Constable, NY) & Marie Catherine Rose Daignel dit Daniels. But can only find John Baptiste Landry listed in the censuses, and on his children’s baptisms, plus on his son’s, Andrew “Andry” Landry, death certificate in Boston, MA, USA.