Quebec’s nineteenth-century legislative debates on emigration are available virtually in two searchable volumes (1867-1880 and 1881-1900). These compilations reveal policymakers’ ambivalence about industrialization as a viable means of curbing outmigration and the rise of domestic colonization as a projet national drawing bipartisan support. Excerpts are available here.

Emigration to the United States was not confined to Quebec, however, and neither were debates on the issue, which reverberated in Parliament. The following all-too-brief overview of federal emigration debates through the first four parliaments (1867-1882) comes from a careful perusal of Hansard, the official transcript of debates in Ottawa. This post only covers House of Commons debates.

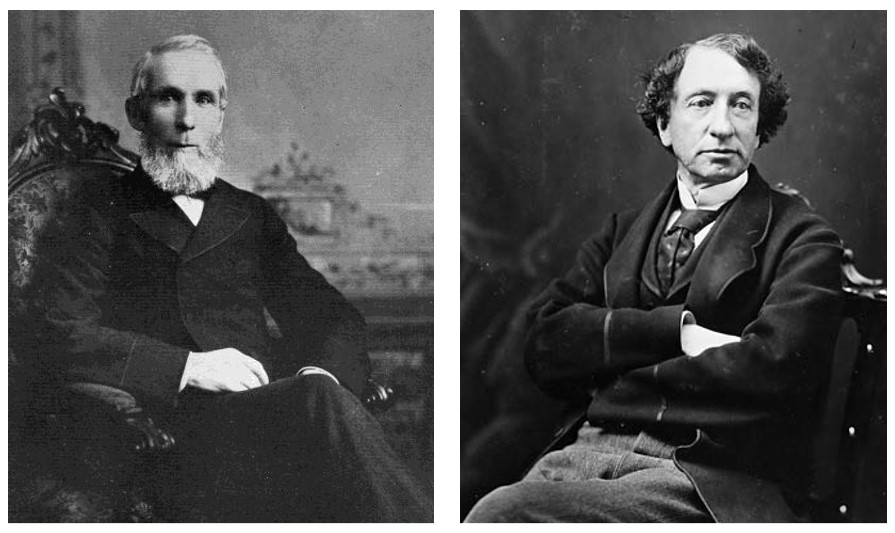

Only two prime ministers held office during this fifteen-year period. John A. Macdonald served until 1873, when the Pacific Scandal led to the resignation of his Conservative government. The governor general then asked Liberal Alexander Mackenzie to form a government. The Liberals triumphed in the ensuing elections but an economic depression imported from the United States marred their time in office. Voters carried Macdonald and the Conservatives back to power in 1878. Macdonald remained prime minister until his passing in 1891.

Thus, Liberals and Conservatives alike had, at one point, the burdensome duty as a government of reducing and reversing outmigration. Ultimately, for slightly different reasons, neither could claim unmitigated success—if success at all.

1. A Multipurpose Tool

Until 1880, the problem of emigration from Canada to the United States was seldom a standalone issue in Ottawa. In other words, members of Parliament presented emigration as evidence when discussing other issues, particularly immigration to Canada, Western development, railway construction, and, as we will see, trade policy.

In the first parliament, New Brunswick’s Albert James Smith intervened in a debate about immigration to Canada to argue that funds would best be used not to recruit abroad, but to keep Canadians at home. Six years later, Louis-Rodrigue Masson, a Conservative member from Quebec, pleaded for funds for repatriation. His motion came during a debate on government assistance to Mennonites who might settle in the West. Some colleagues challenged Masson for conflating two distinct issues, but the proposal stood. With efforts to bring immigrants to Canada languishing, the government could not afford to ignore Canadians who had gone abroad. William McDougall would later assert, as others did, that expatriated Canadians were the best class of settlers for Canada.

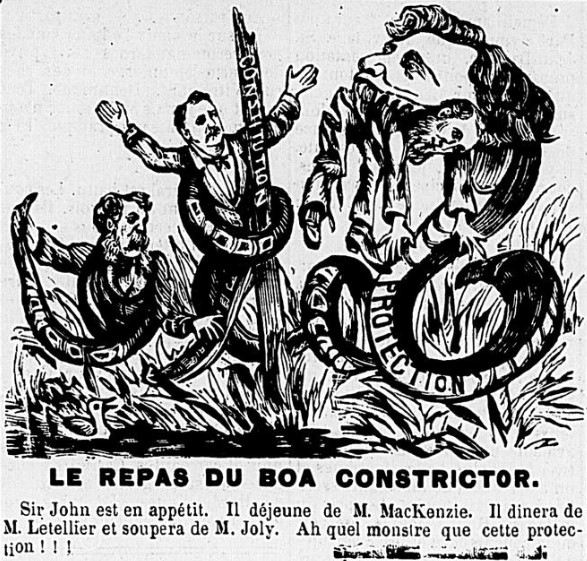

Emigration also arose in connection with the development of Manitoba and the North-West (present-day Saskatchewan and Alberta). Canada quickly grew into a colonizing nation that would develop the Prairies by eradicating Indigenous claims and establishing white settlers. Parliamentary debates reveal quite clearly that English and French Canadians had a shared interest in this nation-building project. Members from Quebec sought to channel expatriated French Canadians to Manitoba just as often as they sought to bring them back to Quebec. Charles Lalime, a federal repatriation agent based in Worcester, Massachusetts, specifically recruited settlers for the North-West; so would C. A. Beaudry in the late 1880s.

2. A Mari Usque Ad Mare

We are still saddled with the persistent myth that late nineteenth-century mass emigration was a Quebec-specific issue. Even at the time, some policymakers were of that mind. In 1880, Philippe Baby Casgrain, who represented the riding of L’Islet, stated before the House that five-sixths of expatriates were French-Canadian. This perception likely arose from the cultural apprehension that came with emigration—declining influence for French Canadians within the Dominion and the risk of rapid assimilation in the United States.

Demographic data has proven Casgrain wrong. The debates of the time also revealed the national scale of the issue, for members from all parts of Canada spoke to the problem of depopulation in their home provinces.

Members from Ontario and the Maritimes rose to press the Mackenzie government on emigration. When the roles were reversed and Liberals led the charge in 1880-1881, the overall portrait was damning. Everywhere the steady stream of migrants had, with renewed American economic growth, turned into a veritable torrent. Opposition members agreed that expatriation from all points had never been so extensive. Although there were regional inflections to the problem, this was a national issue and people everywhere demanded action from their federal leaders.

3. Debt and Taxes

Confederation-era policymakers had to balance national development with limited financial means, particularly in light of the debt load that came with railway construction. They were also tasked with ensuring continued prosperity following the United States’ abrogation of reciprocity (limited free trade) in 1866. Mackenzie’s government nearly closed a new commercial deal in 1874. More active support from the Grant Administration would likely have ensured a vote—and a successful outcome—in Congress.

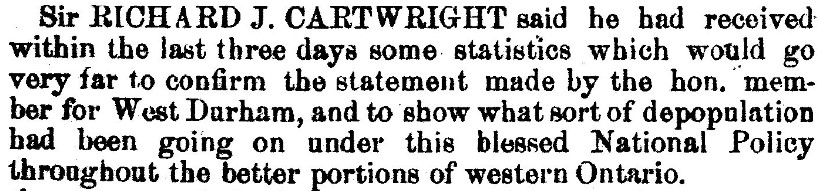

In light of that failure, the Conservatives charted a new direction: high tariffs, they claimed, would enable Canadian industry to develop and thrive, just as protectionism had borne fruit in the United States. Returned to office on the pledge of economic growth in 1878, they quickly implemented their high-tariff platform, the National Policy.

As emigration reached unprecedented levels at the turn of the 1880s, the issue inevitably intersected with the National Policy and its alleged effects. Were people leaving because the high tariffs had led to price increases? Was the National Policy failing to create industrial opportunities? Was it causing “oppression, heavy taxation and ruin,” as New Brunswick’s Arthur Gillmor argued in 1880?

Some Opposition members indulgently stated that the National Policy was not responsible for the exodus—but, they added, neither had the government stanched the flow of people over the border. Richard Gwyn has helpfully argued that in an era of limited economic measurements, emigration and population statistics served as a barometer of people’s well-being. It will be essential in future research to better integrate emigration in the story of the National Policy.

4. Party Hard

Historians have enshrined the National Policy as a cornerstone of Canadian nation-building that voters upheld at the polls in 1891 and again in 1911. But we should not read this apparent consensus back in time. The debates of the 1870s and 1880s were fiercely partisan—and went well-beyond a healthy critique of the National Policy.

While in opposition, the Liberal Party rightly weighed on the government to recognize that mass emigration was real and that it posed a major challenge to the country. Frédéric Houde was likely close to the mark when stating, in 1879, that 600,000 Canadians were now living south of the border. Repeatedly, and in vain, the new Liberal leader, Edward Blake, and his caucus asked for an inquiry.

The Conservative government cast doubt on the Liberals’ figures, which were drawn to a great extent from American sources. Some members conceded that emigration did occur—but by no means was it an exodus. They suggested that emigration occurred in Grit ridings because their representatives were always lauding American success and American institutions. Conservatives also argued that Liberals’ “unpatriotic” focus on Canada’s problems deterred immigration from abroad.

In retrospect, nothing seems more reasonable than the Liberals’ request for answers and for action; they were fulfilling their duty to keep the government honest. The Conservative arguments were, as we will see, often preposterous. But Macdonald and his troops had likely found the optimal long-term strategy: high tariffs would foster native industry and, by offering diverse employment, keep English and French Canadians and recent immigrants from finding their bread in exile.

5. Obfuscation v. Pessimism

The Conservatives deflected blame for outmigration in every possible way. They claimed that the Liberals’ numbers were inflated and that emigration of this kind was temporary. Confronted with Canadian settlements in Minnesota and the Dakotas, they stated that emigration from east to west was a natural movement that also afflicted the eastern United States. Erasing all sense of scale, George-Etienne Cartier argued both in Quebec City and in Ottawa that the very presence of Americans in Montreal sufficed to show that migration occurred in both directions. William Bullock Ives, a Conservative from the Eastern Townships, has his own theory. Ives believed border crossings were rising because, with renewed prosperity, businessmen again had money to travel for commercial reasons.

But inaction also stemmed from the limited policy levers of the federal government, genuine uncertainty about solutions, and pessimism. Spokespeople for both parties at times expressed resignation—more often than not, a belated concession to an insistent Opposition.

I quite sympathize with the hon[orable] gentleman’s desire to secure the return, if possible, of those Canadians who had gone to the United States, but as I stated then there are peculiar difficulties to contend with in doing that. The Government will endeavor to devise some plan if they can by which that may be accomplished to some extent. I am not prepared at present to say how it can be accomplished.

– Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie, February 26, 1875

Those who have left have gone to settle in Manitoba, or in the North-West, and, I regret to say, a large number have gone to the United States. But how can you prevent them going away to settle in the United States? . . . How can you restrain such people, if they are absolutely bent on going to a foreign country? It cannot be done. They are attracted there, as the hon[orable] member for West Elgin (Mr. Casey) said, by their friends who have gone there before them. You cannot prevent this. You may adopt any measures you like, and yet, after all, large numbers of our fellow-countrymen will continue to go to the United States. For these nothing can be done.

– Hector-Louis Langevin, Minister of Public Works, April 12, 1880

This was a question which should be looked into calmly, and cooly, with the view of finding some process which could be put into operation to stop this emigration; and if hon[orable] gentlemen opposite could suggest such a process, they might fairly claim to be regarded as benefactors of their country. But he thought it was impossible.

– Charles-Joseph Coursol, MP and former mayor of Montreal, February 3, 1881

There may be something in the modesty of each of these politicians—who were battling the magnetic industrial economy of an immense, integrated national market that had twelve times Canada’s population.

To summarize, Canadian historians must pay attention not only to those who came, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but to those who left as well. Emigration from Canada was an issue of national historical significance. It played a part in the big policy debates of the nineteenth century, including Western development and commercial relations with the United States. Its effects—and the temptation of an American sojourn—were discussed in towns and in the countryside in all provinces. It also nourished higher-level conversations about the fate of the country as a whole. This is to say nothing of the issue’s fascinating place in federal partisan debates. Perhaps the rich body of literature on the French-Canadian exodus will inspire researchers and highlight the essential Canadianness of emigration.

My “Emigration and the Limits of Public Policy in Quebec and Nova Scotia, 1867-1900” will appear in the next issue of the journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society.

Leave a Reply