Book Review

Bill Schubart. The Lamoille Stories: Uncle Benoit’s Wake and Other Tales from Vermont. Hinesburg: Magic Hill Press, 2013 [2008].

Yet, the rural Franco-Vermonters have a sense of their identity as French people, both those who live on family-owned farms, and those who live in mini-mill towns like Beecher Falls. The French-Vermonter’s identity is tied to his nuclear family and the long tradition of his extended kin. They maintain contact with Quebec through relatives who live close by, and identify with them as individuals rather than some abstract, ethnic identity or national dream. The Franco-Vermonter is neither tied to Quebec’s cultural past nor Quebec’s future, except as they affect relations with his kin across the border. The French-Vermonter who works in small mill towns like Beecher Falls may on the surface have a closer relationship with his cultural traditions: that is, identifiable Franco-American institutions. But those institutions survive only with great difficulty.

– Peter Woolfson, “The Rural Franco-American in Vermont,” Vermont History (1982)

Peter Woolfson has helpfully reminded us that Little Canadas were not exclusively urban. The first Franco-American community—and this is a matter of interpretation—may well have been the settlement of Revolutionary War veterans on the western side of Lake Champlain long before northern New York could boast a city. Vermont had its share of migrant French-Canadian farm laborers who, in time, inspired family and neighbors to join them. In the countryside, they formed communities that were not always visible to the outsider, but that in time refashioned the cultural and economic landscape of the state. Bill Schubart picks up that story with a collection of twenty-two tales that expand how we view both the Franco-American world and rural Vermont.

A widely-published author, Schubart grew up in Lamoille County and attended school in Morrisville. Both his setting and the very presence of his stepfather, Emile Couture, and his kin entailed close contact with the French-Canadian community of northern Vermont. (Couture’s own father, Clovis, was Canadian-born and came to Vermont in 1919, during a spurt of immigration that saw many Quebeckers move south to seek new opportunities and buy affordable Vermont farms.) Schubart went on to earn a degree in French at the University of Vermont. His Lamoille Stories (as well as the follow-up Lamoille Stories II) are a delightful effort to recreate rural life in twentieth-century Vermont and the inescapable French flair of many communities.

The stories may at first seem “foreign” and inconsequential, especially if gleaned from Franco-America’s undoubted urban bias. From reading the big books on the topic, we could easily claim that northern New York, Vermont, parts of New Hampshire, and the upper reaches of Maine were not only economic peripheries, but cultural backwaters as well. We might even think that Schubart supplies the evidence. His stories are entirely divorced from the institutions of survivance—national parishes, Catholic schools, sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste, French-language papers, and Canadian-owned businesses, though all existed in Vermont. Neither is there an “abstract, ethnic identity or national dream.”

Instead, Schubart invites us see the culture beyond the traditional institutions—something which, far from being foreign, is actually timely and relevant to younger generations of Franco-Americans who aren’t bound by narrow structures and inherited definitions of identity. In a refreshing twist, French-Canadian culture is palpable through The Lamoille Stories, but it is seldom explicit. It is imbedded in social relations and ways of life that are taken as a given.

It comes out when we read about “Mon Onc” Ben and when René “laps[es] into his most familiar tongue.” We begin to sense a pattern as the locals patronize Dagnon’s and Brosseau’s and buy Bouyea’s bread. Sometimes it’s not entirely clear where the old Yankee Vermont accent ends and Quebec French begins. Sometimes we see the rich cultural texture that comes with transnational lives, as when the Ferland girls, returning from Montreal, tell their father Laurent about pet stores that sell pigs as domesticated animals. “Ettie-fie doller eh? Tabarnak! Das a lotta dollars for a pig, non?” we hear him exclaim.

Of course, setting aside this blog’s own obvious bias, Schubart’s work isn’t merely about French people doing French things in Vermont. It delves into the fabric of rural life, into the myths and realities of “true Yankee independence,” into hardships and joys that strike a chord, however far removed we might be from Hardwick, Morrisville, and Stowe. It accomplishes what all great literature does: it forces us to empathize and to connect emotionally with people who live in very different settings and lead different lives—including Doc and Morris, who, from their drafty old farmhouse, daily sup on spam and beans in the company of egg-laying hens (at last safe from the incursions of desperate raccoons).

Schubart delivers proximity to the characters; we instantly feel entwined with their lives, and we smile at their quirks. And so, while many historians have ably described the mores, customs, and folk life of French Canadians, from short stories like these we have the additional benefit of intimacy. Individually, then, they connect us with unique and fascinating families. Brought together, they offer a stunning snapshot of the transformations that molded not only Franco-Americans, but Vermont communities as a whole from the 1950s to the 1970s. While manufacturing cities across New England struggled and suffered in those years, agriculture underwent its own difficult transition, and many residents were never lifted by the new economic tide that brought college-educated professionals and tourists to Vermont.

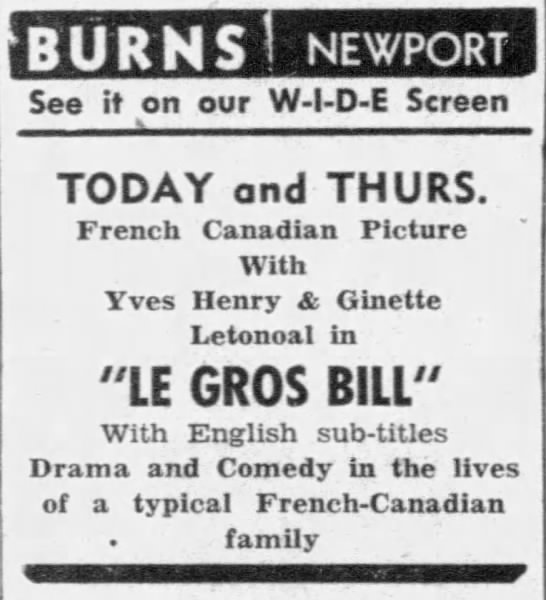

From delightful drives through Hazen’s Notch Road, the typical touristy things in Waterbury and Stowe, a stroll through Swanton, Chinese outings in Newport, obligatory stops for rich coffee and cheap books in Lyndonville, and quests to find relatives in St. Albans and Lowell, you will find—as I have—that all of these quirky, interesting locations lie somewhere between “old” and “new” Vermont. Cultures must adapt and economic change is inescapable. But as the fate of the old ways, including French heritage, is in doubt, so are a broader view of New England history and much-needed perspective.

One of my many adventures in that part of the country continues to resonate for that reason. It involved a chat with a woman who was selling baked treats for 4-H at a rest stop outside of St. Johnsbury. She was a Bonin through her mother—another Franco-American on the margins of established narratives, but whose heritage nonetheless survived. She was dispirited by her daughter’s lack of interest in her roots, her history.

Then and now, I’ve suspected that this young person asked herself, “so what?” and found little that would have tangible bearing on her life. The world of past generations did not speak to her; their words did not reach her. Some cultural activists would answer that the perennial vibrancy of a culture lies in its commercialization. There is something to that. For my part, however, to youths willing to set aside their electronic devices, I would eagerly give Schubart’s Lamoille Stories, which, by enabling us to access a disappearing world, helps enrich our own.

Further Reading

Prior QTP Book Reviews:

- Kimberly Lamay Licursi and Céline Racine Paquette, Franco-Americans in the Champlain Valley

- Caroline B. Brettell, Following Father Chiniquy

- Holly A. Mayer, Congress’s Own

More on Vermont:

- An All-American Town? Ethnicity and Memory in the Barre Granite Strike of 1922

- On Its 50th Anniversary, the Francophonie Can Find New Purpose Despite Mixed Legacy

- Those Other Franco-Americans: St. Albans, Part I

- Those Other Franco-Americans: St. Albans, Part II

- Honoring Vermont’s French-Canadian history

You can find more about Vermont’s rich Franco-American history in my second book, “Tout nous serait possible”: Une histoire politique des Franco-Américains, 1874-1945.

Leave a Reply