Book Review

Holly A. Mayer. Congress’s Own: A Canadian Regiment, the Continental Army, and American Union. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2021.

It may too trite to assert, as scholars have for generations, that the American struggle for independence was complex, messy, and far from linear. But, in the wake of the national holiday, the reminder is a helpful one. The country just celebrated its 245th anniversary—kinda. The Revolutionary War was under way over a year before the Continental Congress adopted the Resolution of Independence. And the resolution was just that—a statement. Independence had to be realized by concrete means, a process that would require many years of bloodshed and toil. Britain did not recognize American independence until 1783 and only then did it turn New York City over to the triumphant Patriots. A British military presence remained in the Old Northwest and on Lake Champlain until 1796. Independence also meant different things to different people. We should ponder its significance to enslaved people of African descent and Indigenous nations.

Historian Holly Mayer brings further nuance in a new book from the University of Oklahoma Press. Mayer studies one of the two Continental regiments raised in the Old Province of Quebec prior to the Declaration of Independence. “Congress’s Own” Regiment, also known as the Canadian Old Regiment, was established in early 1776, during the American Patriots’ occupation of the colony. Forced to withdraw to New York State following the British counter-offensive in the spring and summer of 1776, the regiment would remain in service to the end of the struggle for independence.

Mayer’s work spans the years of the War of Independence almost exactly. The book steers away from a lengthy (and well-known) retelling of the march to colonial rebellion. It does not offer a new interpretation of the prelude to war, nor is it a deep dive into the social and political conditions in 1770s Quebec. Mayer’s story lies in the unique conditions created by the regiment, which, from the summer of 1776, was completely unmoored from Quebec and, as soldiers from other colonies joined, became a multicultural experiment.

Having set the stage with the regiment’s military and organizational context, Mayer introduces the main characters. The leading man is seigneur Moses Hazen, a New Englander with land holdings in Quebec who, after some hesitation, backed the Patriots and earned himself a colonel’s commission. He would lead the regiment to the end of the war. We also meet major figures like Clément Gosselin, perhaps the most famous Quebec insurgent (he appears in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography), and such lesser-known participants as Lieutenant Colonel Edward Antill. As we discover in Chapter 3, as “Congress’s Own,” this regiment could not depend on recruitment through state levies or regular supplies also provided by a state. But recruitment there nevertheless was with the support of the Continental Congress. Hazen’s unit never shed its Canadian character, but, by 1777, the addition of men from New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut in particular had transformed it into a social and cultural mosaic.

The middle part of the book is concerned with this changing regimental identity and military operations in the mid-Atlantic states, from the area surrounding New York City to battles near Philadelphia. The most illuminating chapter for scholars of Quebec history is titled “Canada Again?” The French alliance raised hopes among Hazen and the Canadians that a new invasion of Quebec would be attempted. General Washington was not interested. We need only consider the fate of the first invasion, American fears of French imperial ambitions, and the need to focus on the more immediate objectives of the war. Still, the commander-in-chief kept his options open and sought to appease proponents of an invasion by supporting scouting missions in Canada and the construction of an alternative invasion route in 1779. It was (in part) French-Canadian hands that built blockhouses and cut a path in the wilderness from the Connecticut River almost all the way to Hazen’s Notch in northern Vermont.

The next chapter explores the larger community of the regiment, including women and children who often followed their husbands and fathers during operations. The war was by no means easier for them. Holly Mayer also highlights the rapport between men—frictions and problems with duty and discipline, many of those centering on the troublesome Major Reid.

Mayer’s work concludes with the march from the Hudson Valley to Yorktown, the British surrender, and the uncertainty weighing on soldiers as diplomats bargained in Europe. Hazen’s Regiment was for some time assigned to guard prisoners in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. While state militiamen could slip back home as their terms expired, the Canadians were not so lucky. They remained in the ranks, for they had lost their property and were now dependent on military pay and the promise of pensions. There is no epilogue per se; several pages quickly trace the veterans’ fate, but we are left to wonder about the many legacies of this experiment that became the Canadian Old Regiment.

Congress’s Own is not the type of traditional military history that has an exalted place at Barnes & Noble. Mayer adds to the works of Gustave Lanctôt, George Stanley, and Mark Anderson; however, whereas these authors focused on the invasion of 1775-1776, she pushes the story further in time and sets aside the well-documented tactical aspect. By her attention to structures and relationships, her work is much more akin to Charles Royster’s influential A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1775-1783 (1979), and arguably an equally important contribution to the literature on the army of the Revolution.

Readers with an interest in the topic will no doubt be acquainted with Allan Everest’s Moses Hazen and the Canadian Refugees in the American Revolution (1976), the study that is most like Mayer’s in its coverage. Mayer acknowledges Everest and abundantly cites him; she also looks beyond Hazen and beyond the Canadians. Her vantage point is not strictly ethnic; hers is not a history of the first Franco-Americans as such, or a study of the survival of faith and language in a foreign environment. But the national angle and questions about identity are never far from the surface. The approach is innovative and marks another point of departure from Everest. Mayer extends the concept of borderlands from its purely geographical meaning to a different kind of site—the social universe of military ranks. Just as the regiment proved to be a microcosm of the nascent country, it also embodied its social, cultural, and political boundaries. A regimental history could be perceived as parochial, too narrow to shed light on an era or a society. Mayer is, however, persuasive in suggesting that the experience of Hazen’s men and the larger challenges facing this military outfit provide valuable insight about the war and the Early Republic.

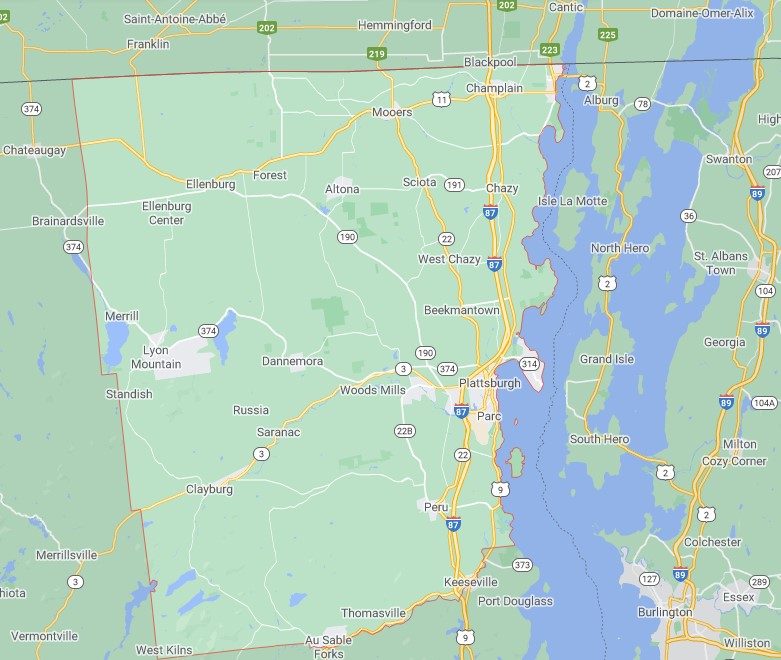

The claim is bold, and the project ambitious. But Mayer delivers. Her research is thorough. She explored physical archives from Washington, D.C., to Philadelphia and from Plattsburgh to Ottawa. Her source base extends to the Revolutionary-era records of the federal Veterans Administration, the papers and Journals of the Continental Congress, historical newspapers, and an impressive number of manuscript collections. The maps, the appendix that lists all of the regiment’s officers, and over 80 pages of endnotes all attest to the seriousness of this endeavor and the depth of Mayer’s research. No work of history is ever truly definitive, but, for the foreseeable future, as much as any book can be, Congress’s Own might legitimately make that claim.

No less, research on this era should go on. Everest and others have explored the postwar fortunes and misfortunes of demobilized Canadian soldiers; that work is not exhaustive and will require further investigation. We can only wonder: Once the regiment disbanded and the veterans (particularly English speakers from the Thirteen Colonies) went their separate ways, what part of the artificial borderland did they carry with them? Was there something unique about “Congress’s Own” that marked these men and their futures? Or, beyond the refugee colony on Lake Champlain, did it simply vanish? In other words, from a historian’s standpoint, if this is a military history, is the regiment’s story primarily useful as a glimpse into a period of war? Or did it have a larger, perhaps long-lasting impact? Additional research will tell.

Students of French-Canadian and Franco-American history may still find Everest’s work more rewarding due to its focus; the same is true of the recent “Promises to Keep: French Canadians as Revolutionaries and Refugees, 1775-1800,” which takes the story into the postwar years. But Holly Mayer’s study is not to be overlooked. Through its conceptual approach and broad source base, it brings much-needed context and helps us understand how messy and diverse the struggle for American independence ultimately was.

This is the third QTP book review. The first, on Kimberly Lamay Licursi and Céline Racine Paquette’s Franco-Americans in the Champlain Valley, is available here; and the second, a review of Caroline Brettell’s Following Father Chiniquy, here.

For more on the French-Canadian soldiers of the Revolution, check out these posts:

Leave a Reply