Book Review

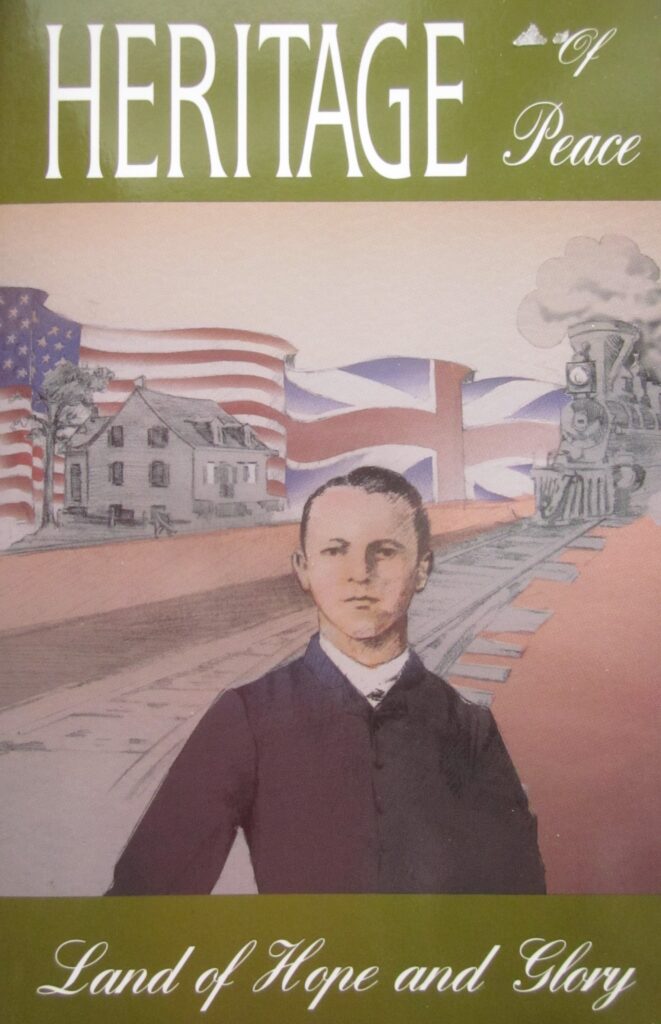

Corinne Rocheleau Rouleau and Louise Lind (editor), Heritage of Peace – Land of Hope and Glory. Cumberland, R.I.: Jemtech, 1996.

In Heritage of Peace, we may have one of those rare cases where the author is more interesting than her subject.

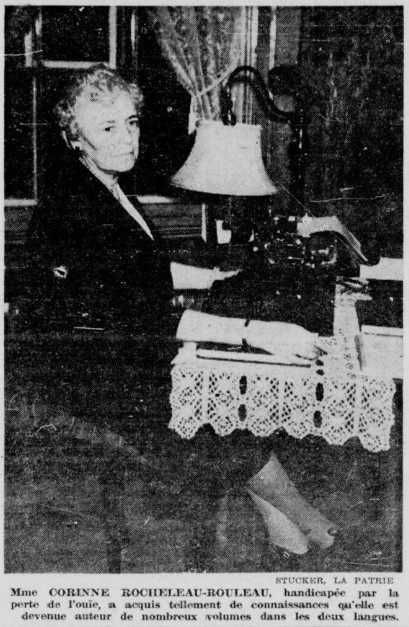

That author, Corinne Rocheleau Rouleau (henceforth Rocheleau to avoid confusing her with her husband), was a multitalented, bilingual writer, scholar, and advocate for the physically impaired. Her life and career took her from Worcester to Washington, D.C., to Montreal and into the public spotlight. Short biographical portrayals of Rocheleau include Armand Chartier’s in the Dictionnaire des auteurs franco-américains de langue française and Béatrice Belisle MacQueen’s in Steeples and Smokestacks (first published in La femme franco-américaine). Even so, from the perspective of the Franco-American pantheon, she remains a relative unknown. Thus we should preface this book review with a hope that she will herself receive full-length biographical treatment.

Rocheleau was born to naturalized French-Canadian immigrants in Worcester in 1881; a sister, Elise, would become well-known as a teacher in the Worcester area. A childhood event announced the course of Rocheleau’s life. She lost her hearing at age 9. Her family sent her to the Institution catholique des Sourds-Muets in Montreal, enabling her to complete her studies, recover her speech, and find a larger community of people with the same affliction. In 1927, she would pen the story of Ludivine Lachance, a Beauceronne who was blind, deaf, and mute and who learned to communicate thanks to the Institution des Sourds-Muets. Rocheleau dedicated the book, appropriately titled Hors de sa prison, to her own father. Her work resulted in a “prix d’honneur” from the Académie française—no small achievement for a deaf Franco-American woman from Worcester.

Her advocacy earned her American renown in 1930. With Rebecca Mack, she co-authored a landmark report, Those in the Dark Silence, under the auspices of the Volta Bureau, providing valuable information on the needs of the deaf and blind in Canada and the United States.

Then there was Rocheleau’s other passion, history. In the 1910s, she published Françaises d’Amérique, which celebrated the women of New France. She contributed to La Revue canadienne, Le Travailleur, and other popular periodicals but also to more learned publications. In the 1940s, she notably contributed a biography of Dr. Alphonse Daudelin and a slice of Revolutionary War history to the Société historique franco-américaine’s Bulletin. She received the Société’s medal for her historical work in 1947. Five years later, the Association Canado-Américaine awarded her its Prix littéraire for her Laurentian Heritage, an overview of life in nineteenth-century Quebec.

In 1930, at age 49, Rocheleau had married Wilfrid Rouleau, a civil servant in Washington. Rouleau, as we will see, also had ties to Worcester. He was then a widower, having lost his first wife in December 1929. The new couple lived in Washington for several years. Rouleau resigned his position and they settled in Montreal. Rouleau passed away in 1940. Rocheleau returned to the Institution des Sourds-Muets and entered one of her more prolific periods. She died in November 1963.

Corinne Rocheleau likely penned Heritage of Peace while immersing herself in history after her husband’s death—a work that was both a tribute and a means of giving some permanence to the experiences he had shared with her. Her “Silhouettes et cadres franco-américains 1880-1900,” published in the Bulletin of the Société historique franco-américaine in 1942, covers approximately the same period and figures, and may be taken as an early draft of the book. (Rocheleau was one of two women to contribute to that issue of the Bulletin; the other, Yvonne Lemaître, similarly deserves greater historical attention.)

In Heritage of Peace, Rocheleau shares her husband’s life story, but treads uncertainly between fiction and biography. Her husband appears not under his own name, but as Justin Rivier; his first wife, no longer Mathilde, becomes Cordélie. Other elements are not quite historical. The death of Rouleau’s mother and his journey to the United States actually occurred later than Rocheleau suggests. But Rocheleau was likely working from the recollections her husband, from his own imperfect memory, had shared with her in their ten years together—and perhaps without documentation, though a 1941 publication refers cryptically to Wilfrid’s “cahiers anecdotiques.” That being established, contextual clues would indicate that the author was seeking to convey, as accurately as possible, Rouleau’s Franco-American story. The closest Franco-American work in this genre is likely Félix Albert’s Histoire d’un enfant pauvre, a first-person immigrant narrative also put down in writing by someone else.

Young Rouleau—to use his name rather than the fictionalized version—left the family home in Saint-Cuthbert, north of Montreal, when just a teen. An older brother stood to inherit the farm; his father seemed to have the help he needed until he retired from active life. Rouleau’s wanderlust drew him to the United States, to which neighbors and an uncle had already removed. He found a sympathetic ear in his parish priest, a friendly presence who at times tempered Rouleau’s excitement. When the issue was broached at the dinner table, Rouleau’s father made no objection to his departure. They agreed that Wilfrid would go to Michigan to work on his uncle’s farm.

But the youth had other plans. From Montreal he set a course for southern New England. Through his experience, we feel the thrill of boarding a train for the first time—and the disappointments. The compartments were overcrowded, passengers had to rely on what little food they had packed, and the cars quickly filled with smoke. Mile by mile, the journey became more uncomfortable. Thanks to Rouleau’s stop in Montreal, we also meet the first of many (real-life) historical figures with whom he crossed paths: J. B. Lucier, the railway agent and Quebec repatriation official.

Rouleau had set his sights on Chepachet, Rhode Island, having heard of the small mill town while in Saint-Cuthbert. This was a sobering introduction to American life. Rouleau was disturbed by the wide gap between rich and poor. He was equally troubled by the number of heads of household who didn’t work but relied on the labor of wives and daughters. He also deplored the ignorance of his compatriots: they spoke a poor French, had no schools or churches, and neither found nor sought opportunities for advancement. Even on his departure from Quebec, Rouleau had determined that mill work wasn’t for him. The sight of Chepachet and an industrial accident that injured his hands settled the matter.

On he went to the more refined Woonsocket and then to Worcester, a city of machine shops with good wages. By the turn of the century, according to Rocheleau, Worcester’s French Canadians were as a whole doing well. They sent their children to school and bought property. Rouleau found an opportunity in the printing trade and never looked back. He worked with a long line of editors and printers, each more eccentric than the last. Rocheleau’s depiction of the odious François Odier is especially entertaining.

After a stint in New York City, during which time he married Mathilde Royer, Rouleau returned to Worcester and worked for Le Travailleur. This was after Ferdinand Gagnon’s death, when control of the newspaper passed to his brother-in-law, Charles Lalime. The editor, Emile Tardivel, penned long editorials inveighing against the “Americanizing” archbishop John Ireland, but did not tend to his part of the paper’s management, causing the printing crew constant frustration. He eventually moved to New Hampshire.

Lalime struggled to maintain Le Travailleur on a sound footing and sold the paper to a silent conglomerate led by Josiah Quincy, a Democratic organizer. Quincy ultimately bought some twenty French-language papers ahead of the presidential campaign of 1892 and consolidated all of their operations. Both the content and the physical issues would be produced from a single facility in Lowell. Quincy asked Rouleau to run the print shop, which he reluctantly agreed to. (Rouleau’s sympathies were on the Republican side, but Quincy never made politics a condition of employment.) Benjamin Lenthier, formerly of Glens Falls and Plattsburgh, would run the editorial team.

Rouleau didn’t like the logistics (Quincy “did not realize the complexities of the undertaking”), Lowell (“a sort of big and bloated Chepachet”), or Lenthier (“nothing showed up in him but a small town demagogue”). But he ensured it ran smoothly down to the end of 1892—at which time Democratic subsidies dried up.

While in Lowell, Rouleau got to know prominent businessman Joseph Chalifoux and Father André Garin, founder of St. Joseph Parish. More encounters of the kind would come. Quincy offered his printer ownership of the newspaper syndicate, which he easily turned down. Quincy, now headed to Washington, then offered him a position at the Government Printing Office as a reviewer and a translator. Rouleau accepted.

Rocheleau provides a fascinating portrayal of middle-class Franco-American life in an unusual setting—as she does earlier in the book, following Rouleau and his first wife through Worcester’s social circles. The glimpse of early twentieth-century Washington is worth reading, as is her account of Major Edmond Mallet, the civil servant whom Rouleau befriended. Rocheleau’s work, based again on her husband’s words, is an essential source on Mallet’s struggle to remain in his position and have his voice heard in government.

The author’s voice carries loudly in the final few chapters. We sense that this is her opportunity to editorialize. She uses a case of schoolyard bullying—Wilfrid’s son Louis being tormented by virtue of his ethnicity—to launch into long treatise on the French contribution to making of the United States. This section reads much less as a slice of Rouleau’s life than as a historical treatise inspired by Rocheleau’s other publications, even if the words (no doubt imagined) are attributed to Rouleau. We cannot but wonder again about the extent of the author’s artistic license; which opinions were hers, which were her husband’s.

For those who are acquainted with Franco-American history, Rocheleau’s significant emphasis on metropolitan French (rather than French-Canadian) contributions to the country is disappointing but predictable. We see more of the age of exploration and Lafayette and Rochambeau than Quebec or the immigrants who settled in the United States in the nineteenth century. There is no denying that at the time Rocheleau wrote this account, Franco-Americans continued to depend on France for prestige and legitimacy—a generation later, we know, they would pin their hopes on an increasingly assertive Quebec. Too often, perhaps, has the source of confidence and self-affirmation been external.

As for this book’s significance, the “filtered” first-person perspective is in itself valuable, as personal accounts of the migratory process are relatively few in the corpus of Franco-American sources. The middle-class perspective—not as intellectual discourse, but as social history—is arguably even more precious. We quickly become aware of the class biases that Rouleau harbored. His time in Lowell evinced a conscious separation from the textile workers who lived in “miserable” tenements. There were also ethnic biases, as we find in Chapter IV. Either Rouleau himself or his biographer insisted on the common “stock” or “blood” of the French, British, and Irish and deplored the arrival of immigrant groups from other regions of Europe. This less stellar aspect of Franco-American history must also be acknowledged and confronted.

For these reasons and more, Corinne Rocheleau’s little-known Heritage of Peace deserves to be rediscovered. More than that, we hope that Rocheleau’s own impressive life and career will enter a broader conversation on both sides of the border.

For more on Franco-American women:

- Women’s History Month: La Femme Franco-Américaine

- Women’s History Month: The Franco-American Press

- Franco-American Women as Political Actors, 1890-1920

Other essential links: Franco-American Women’s Institute; Moderne Francos; Abby Paige.

Prior QTP Book Reviews:

- Kimberly Lamay Licursi and Céline Racine Paquette, Franco-Americans in the Champlain Valley

- Caroline B. Brettell, Following Father Chiniquy

- Holly A. Mayer, Congress’s Own

- Bill Schubart, The Lamoille Stories

I taught her play in my course I researched and designed at the University of Maine cross listed for the Franco-American, Women/Gender and Maine Studies Programs, which was translated and is published in the anthology I edited, Canuck and Other Stories. The play, Françaises d’Amérique, Frenchwomen of North America by Corinne Rocheleau Rouleau, (1881-1963), translated by Jeannine Bacon Roy, is a one-act play which features the heroines who helped settle New France. This play proves their presence on the North American continent and is as fresh today as the day it was first presented. This is an important play in regard to the literary tradition of the Franco-American, French-Canadian heritage. A description of the course, no longer offered, is at the link below.

Link for the course: Franco-American Women’s Experiences https://www.fawi.net/bien.html

This is great information – thank you Rhea!

This book was in manuscript form, in the possession of my uncle, Charles Rocheleau, Corinne’s nephew. He entrusted the manuscript to another cousin, Louise Lind. At the time the book was published, I believe my uncle had some dissatisfaction with the work. I have no idea what if any changes she made to the manuscript but it would be interesting to see the original unedited version.

As for the play Corinne wrote. I believe it was originally performed in Worcester though I’m not sure of the occasion. La Maison Francaise at Assumption College in Worcester has much information on Worcester’s French-Canadian families as does the book, La Livre d’Or.

Forgive me if you already know all of this but I thought I’d add what information I know.

Amazingly, I just found this reference to Heritage of Peace, written by a cousin in 2014 after my uncle Charles Rocheleau’s death. Anne Rocheleau referenced here was my mother, and David is my brother:

…in visiting “ David’s mother, at the Briarwood in Worcester, Anne showed me a book that Corinne had written. Corinne wrote in a style most definitely not influenced by Ernest Hemingway or journalism, with many complex sentences, as a quick look into the book indicated. That style suited the opening description of the St Lawrence River. As the sentence rolled, line after line, one concluded she had tried to recreate the steady, pulsing power of the river through the style of her periodic sentence. It must have gone on for 20 lines.

Anne said the book had been translated and showed me a copy. It is no pleasure to be critical, but the translation reflected nothing of Corinne’s style. Its short, choppy, unadorned sentences seemed suited to a reader for students in the third grade of grammar school, or maybe earlier, but without the schoolbooks’ charm.

I have looked for the French original and have failed to find it. I know the family has good writers. It should be a pleasure to translate the work, though time-consuming, and disseminate it privately, something like the Russian samizdat, since the translator, who dared to call herself the translation’s co-author, apparently has the rights.”

Bonjour Jeanne. Thank you for sharing these details and clarifications. I will be sure to connect with my peers at the French Institute for further information about Corinne. As for the book manuscript, it is unfortunate that the literary style was literally lost in translation. I hope the French original can be retrieved and disseminated.