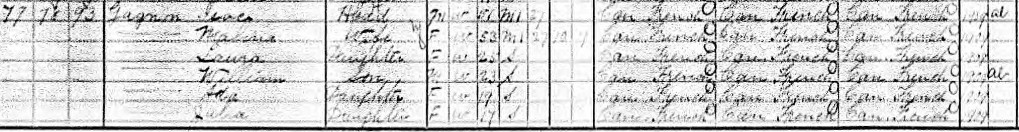

For three years my great-grandmother, a Gagnon by birth, was a Lowell mill girl. She was not one of those off-the-farm Yankee mill girls of the 1830s—I’m not that old. But she was just off of a farm, only farther north. The Gagnon family moved from the Drummondville area of Quebec to Lowell in 1908. Young Laura was married to a Quebec man ten years her senior in 1911 and, in la belle province, on a farm, they remained. Whether she ever talked at length about her American sojourn, I do not know—the story did not reach my mother’s generation. Her story nevertheless merits our attention, not least as a gendered experience.

Laura—soon to be madame Boisvert—provides us with an opportunity to enrich Franco-American history with “new” (i.e. forgotten or overlooked) stories and to do justice to its true complexity. We should keep looking beyond the “Steeples and Smokestacks” that have animated so much of our historical discussions—not that they are untrue, but often incomplete. Like borderlands and transnational history, the new gender history of the last thirty years provides Franco-American scholars with just such an opportunity, all in the interest of a fuller, more sophisticated narrative.

This might mean, specifically, determining how the meeting of French-Canadian and American culture molded the experience of immigrant women and their descendants. It also means using different tools of analysis. By simply studying women through the same lens as we do men, blindly replacing one set of characters with another, we would overlook structures of inequity, uneven relations of power, and different conceptions of opportunity. To represent these realities while doing justice to the immigrant experience and to the role of ethnic custom is no small task. That challenge might explain why, although a distinctly female experience shines through informal conversations and oral interviews, the scholarly literature on Franco-American women still seems to be catching up to the larger field of women’s and gender history.

The challenge is also methodological. So much of the written material on Franco-America flowed from the pens of priests, people of commercial and professional standing, and male editors. The bulk goods of social history, census records and the likes, are often the basis for quantitative studies that tend to erase women’s individualities. An apparent safe refuge appears in the “social notes” of contemporary newspapers, though they are necessarily skewed towards an ideal of domesticity.

Recent research on Franco-American women still emphasizes the experience of the wage-earning population while offering new insights. One such study is Marie-Eve Harton’s Ph.D. dissertation at Université Laval. Harton’s broad, statistical comparison of fertility rates in Quebec City and Manchester, N.H., at the turn of the twentieth century reveals makes important connections:

- Immigrant French-Canadian women and first-generation Franco-American women worked outside of the home just about equally.

- In 1880, the fertility rate of French-Canadian women in Manchester was highest among families whose primary breadwinner belonged to the skilled working class (as opposed to unskilled workers or the petite bourgeoisie, for instance). The rate for other occupational classes would catch up over the course of the next generation.

- The average number of children to every Franco-American woman was, among wage earners, half of what it was for non-working women. (All sorts of factors are possible here, from access to information about reproduction and conscious family planning to the risk of child mortality and the possibility of resorting to orphanages within the first group.)

- A high number of siblings, especially younger siblings, had a negative relation to young girls’ educational levels.

- Endogamous relationships (i.e. between French-Canadian partners), French unilingualism, and residency in a concentrated ethnic community all tended to increase fertility rates.

Although Harton discerns trends rather than presuming to provide end-all explanations, her work, like other studies, suggests how diverse female Franco-American experiences could be, all depending on means, status, community, etc.

Florence Mae Waldron has similarly complicated what might be seen as the “standard” life of Franco women. Taking two major destinations for immigrants as case studies, she explains,

Unlike Lewiston’s surplus of French Canadian women, canadiennes in Worcester were fewer than their male counterparts, leaving them no shortage of available marriage partners. With plenty of men to choose from and fewer choices for attractive, well-paying jobs, Worcester’s canadiennes were less likely to hold an outside job at any given moment in time, more likely to marry at a younger age, and more likely to remain at home once married, whereas the reverse was true in Lewiston.

French-Canadian women had always worked, of course, and they continued to do so in the home. Immigration to the U.S. Northeast provided many with the novel opportunity to earn wages outside of the home, thus contributing to the family economy in a more tangible way. Waldron notes that many women, especially young women, felt a sense of emancipation from living in cities, working daily with other women, and earning money directly.

On the other hand, in a different article, Waldron adds that some women continued to pursue an ideal of domesticity (she even calls it dependency), which they saw as fulfilling the traditional Catholic family ideal and achieving American middle-class respectability. Some women actually bucked the Church, and earned allies in the press, when resorting to legal means to force men to live up to their role as breadwinners.

All of this is to suggest that women were active participants, though at some disadvantage, in the making of their own circumstances. This was true in the household and in the family economy, certainly. But they also defied misbehaving priests and agitated—even if it meant disrupting religious services—for their perceived cultural rights. From 1920 onward, politicians who courted the “woman vote” showed that Franco-American women’s power and influence stretched beyond religious and cultural organizations. Hardly, then, were they the silent partners, or the domestic protectors of language, faith, and customs, that they often seem to be in standard historical treatments. (In one study, Magda Fahrni and Yves Frenette reveal that in one Laconia, N.H., household, the Franco-American mother had very much an American spirit, rather than consciously serving as the guardian of “pure” Canadian traditions.)

I would suggest that the next step, if we are to build a more inclusive Franco-American narrative in this direction, is to capture more individual voices. This can be “top-down” history only to a point. Beyond Camille Lessard Bissonnette, Marie Rose Ferron, and Grace Metalious, few Franco-American women (or girls) achieved broad name recognition in their own lifetime—that is, until the second half of the twentieth century. (See here, for instance.) Juliana L’Heureux has shared the fascinating stories of Emma Morin, Sister Myriam, and Tante Blanche, lesser-known figures who may again inspire researchers to look beyond both an undifferentiated mass of textile workers and the “big names.”

So, what about middle-class women, for instance—those who were not expected to labor in mills? Did they join all the do-gooder causes dear to “mainstream” white American women, or perhaps their ethnic equivalents? What did respectability look like for Franco-American women? What type of education and influence could one aspire to, whether in Church groups, civic activities, or ethnic organizations like the Fédération Féminine Franco-Américaine? This direction in research, supported by individual case studies, promises to be especially fruitful while addressing a glaring omission in our understanding of Franco-Americans—especially as more and more families acceded to the middle class over the course of the twentieth century.

As for mon arrière-grand-maman, her story, too, needs to be told outside of statistical surveys, however daunting the prospect. Amid conceptual and methodological challenges, the historical discipline entails a certain hope that we can approach an ever-more accurate and complete depiction of the past. We may not have a moral obligation to the departed, but we honor ourselves and each other in ensuring that no voice is omitted by virtue of class, gender, ethnicity, or any other element of self-definition.

The website of the Franco-American Women’s Institute includes insightful articles by female writers and a great deal of history, too. Readers should also take this opportunity to check out the official website of Women’s History Month and Women Also Know History.

Select Bibliography

CHOQUETTE, Leslie. “Les rêves américain et canadien des Jobin : une famille bourgeoise de Québec aux Etats-Unis, 1890-1990,” International Journal of Canadian Studies 44 (2011), pp. 111-118.

DeROCHE, Celeste. “‘These Lines of My Life’: Franco-American Women in Westbrook, Maine, the Intersection of Ethnicity and Gender 1884-1984.” M.A. thesis, University of Maine, 1994.

FAHRNI, Magda, and Yves FRENETTE. “‘Don’t I Long For Montreal’ : L’identité hybride d’une jeune migrante franco-américaine pendant la Première Guerre mondiale,” Histoire sociale/Social History, 41-81 (2008), pp. 75-98.

HAREVEN, Tamara K. “The Laborers of Manchester, New Hampshire, 1912-1922: The Role of the Family and Ethnicity in Adjustment to Industrial Life,” Labor History, 16-2 (1975), pp. 249-265.

HAREVEN, Tamara K., and Randolph LANGENBACH. Amoskeag: Life and Work in an American Factory-City. NYC: Pantheon Books, 1978.

HARTON, Marie-Eve. “Familles, communautés et industrialisation en Amérique du Nord : La reproduction familiale canadienne-française dans les villes de Québec et de Manchester (New Hampshire), 1880-1911.” Ph.D. dissertation, Université Laval, 2017.

HUDSON, Susan P. “Les Soeurs Grises of Lewiston, Maine 1878-1908: An Ethnic Religious Feminist Expression,” Maine History, 40-4 (2001-2002), pp. 309-332.

QUINTAL, Claire. Editor. La Femme Franco-Américaine – The Franco-American Woman. Worcester: Editions de l’Institut français – Assumption College, 1994.

SHIDELER, Janet. Camille Lessard-Bissonnette: The Quiet Evolution of French-Canadian Immigrants in New England. NYC: Peter Lang, 1998.

TAKAI, Yukari. Gendered Passages: French-Canadian Migration to Lowell, Massachusetts, 1900-1920. NYC: Peter Lang, 2008.

WALDRON, Florence Mae. “The Battle over Female (In)Dependence: Women in New England Quebecois Migrant Communities, 1870-1930,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 26-2 (2005), pp. 158-205.

WALDRON, Florence Mae. “‘I’ve Never Dreamed It Was Necessary to Marry!’: Women and Work in New England French Canadian Communities, 1870-1930,” Journal of American Ethnic History, 24-2 (2005), pp. 34-64.

Leave a Reply