The subscribers . . . beg leave to lay before Your Excellency their sad situation, seeing themselves abandoned in general by those who have conducted them in the just cause they have been engaged in since 1775 . . . in consequence of orders, and promises as well from Your Excellency as from the honorable Congress, that all the citizens of Canada who would join them should be protected and receive satisfaction for their trouble[,] in consequence of these promises the Canadian refugees did not hesitate to do all in their power to gain the object it has pleased God to grant us.

– Canadian refugees to General George Washington, July 14, 1783 (Washington Papers)

You demand instant payment. I have no money to pay you with.

– Robert Morris to Liébert, Selin, Gosselin, and Dionne, January 23, 1784 (Morris Papers)

One wonders about the emotion the Canadian veterans must have felt on seeing Fort Ticonderoga and the waters of Lake Champlain for the first time in seven years—seven long years of hardship and war. They were tantalizing close to the land of their birth. Unwelcome in the Province of Quebec due to their revolutionary sympathies, they had left in the chaotic retreat of the Continental Army in 1776. Now, with the return of peace, they were returning north. Their final destination was just short of Canada, however. Many had lost all of their belongings; most were estranged from family and friends. They might still face legal and political reprisals. But there was the promise of land on the shores of Lake Champlain.

The veterans’ future was as uncertain as ever in 1783. Their pay was in arrears. Pensions had yet to materialize. Unlike states, which provided for their own regiments, Congress did not wield powers of taxation to support the men of the Continental Army. Unlike most revolutionary soldiers, the Canadian veterans had no home to return to. They were adrift, with almost nothing to show for the immense sacrifices they had made.

Compensation would come in a more tangible form. In 1784, New York State established the Canadian and Nova Scotia Refugee Tract in the northern part of the state. Though Congress would follow suit with projected grants in the Northwestern territories, the Canadians availed themselves of the land in upstate New York—that is, when they did not sell their parcel, often at a loss, to get cold, hard cash.

The work of clearing that land and preparing it for families—some soldiers’ wives and children had weathered the war as refugees in the Albany area—actually began in 1783 under the leadership of Benjamin Mooers, the former commander’s nephew. Mooers brought his cousin and ten French Canadians. They traveled up the Hudson, through Lake George, past Ticonderoga, and into Lake Champlain. They took down trees, built cabins, and began planting, first at Point Au Roche and then at Trombley Bay. They were not alone on the lake. Mooers wrote of seeing Indigenous peoples in canoes as well as Loyalists seeking safety on the other side of the line.

A proper colonizing expedition that involved refugee families appears to have come in 1786. At that time, the settlers were still dependent on rations furnished by the War Department, evidence of the lean times that followed wherever they went.

There were more than 160 Canadian refugees on the shore of Lake Champlain in 1787. The first federal census, taken in 1790, points to a shrinking Canadian population. Some people, we know, were able to return to Canada; others may have spied better prospects outside of this borderland region rife with conflict—infighting, but also threats from the continued presence of British forces on the lake.

Trade grew with Jay’s Treaty and the influx of Anglo-American settlers. The French-Canadian settlement held, its population growing to approximately 225 by 1800. The census taken in that year gives the names of families who had not received land as compensation for revolutionary service, the Tremblay clan for instance. Some veterans like Pierre Charland and Clément Gosselin had gone to live in Canada but would return to Lake Champlain.

The names of many of the original colonizing settlers appear in Coopersville church records in the 1840s. Memory of revolutionary service was kept alive generations beyond the War of Independence, as we see from petitions to Congress filed in the years prior to the Civil War. The petition of Marie Vincelet, who sought compensation pledged to veterans and their survivors, presented her claim when she had become quite elderly:

May Vincilet [sic], who is certified to be a credible person, testifies that she was living with her mother at Chambly, in Canada, in 1779, who was then a widow woman, when Captain Pierre Ayott came to her mother’s house from the States to spy out the condition of the country and the British forces in the Canadas, and that he made her mother’s house his hiding-place while on this hazardous service; that he there married her mother, and she and her mother followed Captain Ayott into the United States, and followed him in the army through the whole war, and after the war they settled in Champlain, in the State of New York, where he died, in 1814.

The shared experiences that evolved into shared memory helped anchor the French-Canadian community in upstate New York. So did culture. Amid hard economic times, the veterans retained much of their heritage. In the 1780s, refugees petitioned Congress en français. Even before commerce flourished on Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River, they sought out religious rites in Chambly and in the Saint-Jean area. Many veterans and their children married in Canada and had the next generation baptized there. Their horizons were transnational, but they lived under American institutions and mixed with other groups.

They were, in effect, Franco-Americans—we might even say the first Franco-Americans. Such places of French-Canadian settlement as Vincennes and Kaskaskia, in the Midwest, not only preceded the Revolutionary War; they were offshoots, as creolized communities, of New France. Residents of these villages did not move to the United States; they saw the American republican experiment come to them. The Canadian refugees on Lake Champlain were, on the other hand, migrants. Through the tumult of war and peace, they experienced cultural, economic, and political conditions which, with local variations, would come to represent the essence of Franco-America.

Since the early twentieth century, researchers have regularly returned to the founding of the United States and the simultaneous founding of Franco-America. Although wildly insufficient, there has been some acknowledgment of French-Canadian experiences in the United States between 1776 and 1860. But the places where this new world began hardly get their day in the sun.

There is an opportunity for better and wider recognition of Clinton County, at the northeastern corner of New York State, as the earliest meeting place of French-Canadian culture and American life—a place that would continue to receive migrants from Quebec well into the twentieth century. Such recognition would create space in our historical imagination for Franco-Americans whose experience never involved large industrial cities. It would help restore French Canadians as decisive actors in the making of far upstate New York (as well as Vermont, northern New Hampshire, and central and northern Maine), where they were often proportionally more numerous than in the likes of Lowell, Massachusetts. It would also help us think of the various permutations of Franco-American life, a necessity considering how little the field has changed in the last forty years.

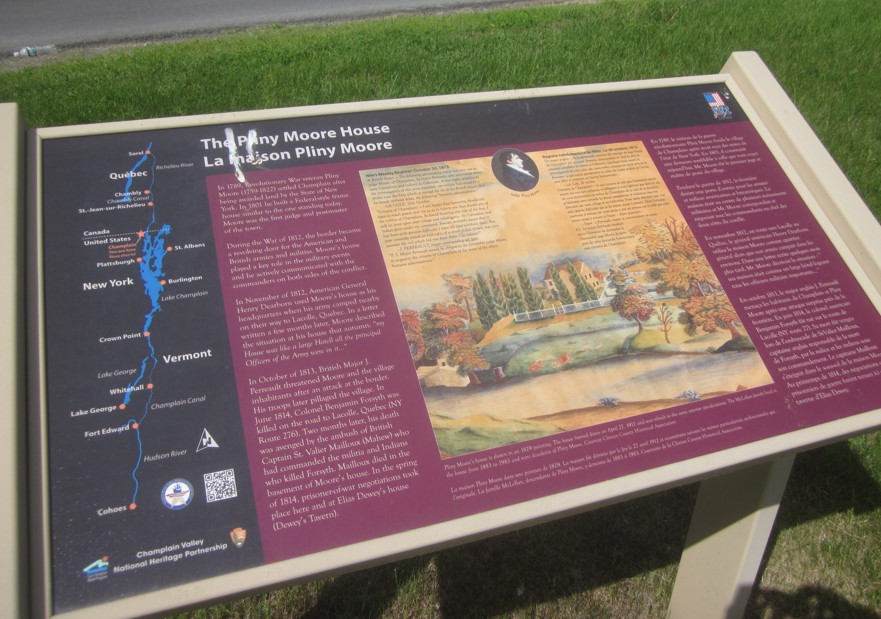

The infrastructure is present, from bilingual historical signage to regular traffic from Quebeckers, from impressive collections at SUNY–Plattsburgh and at the Samuel de Champlain History Center to a recent venture in culinary culture, the Poutine Challenge. Oh, and let’s not forget the two (count ‘em!) statues of Samuel de Champlain and other sites of memory.

As we approach the 250th anniversary of the Revolutionary War, we might at last, by acknowledging the first Petit Canada, honor the full span of the Franco-American experience and the ways in which it has intersected with American national development. This would have the effect of drawing new attention to Franco-American history—and maybe to Franco-American culture—beyond “steeples and smokestacks” which, however iconic, cannot alone tell the story in its entirety.

Further Reading

I have previously written about the Canadian refugees on this blog with regard to the challenges they faced during and after the war. The Mignault family is especially notable for its lengthy cross-border connections and its acts of memory. A more in-depth look appears in the Journal of Early American History as “Promises to Keep: French Canadians as Revolutionaries and Refugees, 1775-1800” (2019). See, also, my review of Holly Mayer’s work on Hazen’s Regiment.

The “acts of memory” of veteran petitions were communicated to the Senate and the House of Representatives by the Committee on Revolutionary Claims. The Moorsfield Antiquarian, published in the 1930s, provided glimpses of primary documents that are essential in understanding the early history of the region.

Virginia E. DeMarce’s extensive series in the genealogical periodical Lost in Canada? provided the most comprehensive compilation of Canadian refugee soldiers; her work also appeared as Canadian Participants in the American Revolution: An Index. A shorter list of soldiers drawn from the Daughters of the American Revolution appears online. For researchers, I have compiled (below) the Canadian refugees who petitioned Congress in 1787 and residents of the Town of Champlain in 1790 and 1800. Individuals highlighted in yellow are ascertained veterans with claims to land in the region.

Etienne Parent, (Sainte Marie) is on Demarce’s list. His grandson Jean Baptiste (spouse Catherine Drouin) settled in St. John River Valley in 1827. My application to DAR is in process for Etienne Parent!