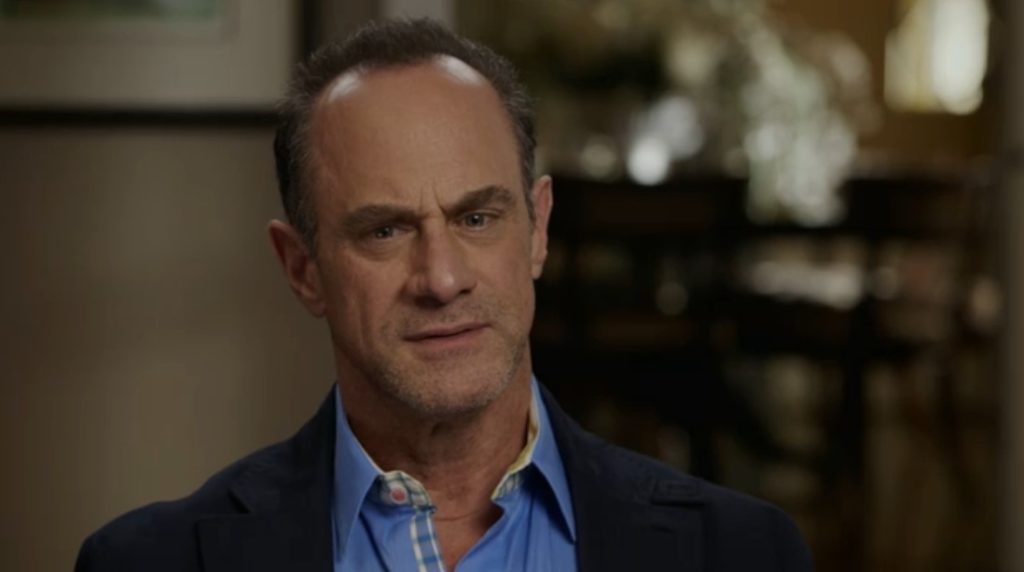

Not a week goes by that we do not find new and interesting articles, videos, and conversations about Franco-American history and culture. Lately, at Moderne Francos, Melody Desjardins draws attention to traditions old and new that might help spark a cultural renaissance. Over at My French-Canadian Family, Tim Beaulieu has the story of actor Christopher Meloni who, as we learned from a recent episode of Finding Your Roots, is Franco-American. Full disclosure: I was a research consultant for an aspect of Meloni’s genealogy that didn’t make the final cut—his family came through Berlin, New Hampshire, and that, I think we can agree, would merit another episode. Luc Trépanier continues to share expressions that are unique to Quebec and to the French-Canadian diaspora, a great starting point for English speakers who wish to better understand quirky idioms.

As it happens, Melody, Tim, Luc, and I manage the Rêve de Gagnon group on Facebook. The group, which now boasts some 1200 members, is a bilingual platform dedicated to bettering mutual understanding between francophones and francophiles in Quebec and the United States. We share all sorts of content of common concern and anyone can join… on promise of good behavior. Okay, two more plugs. The Franco-American Centre in Orono recently hosted (virtually) the French-Canadian Legacy Podcast for a fascinating talk and Q&A. A recording of the exchange will soon be available on the University of Maine’s Digital Commons. This past week, the Centre also hosted Mark Paul Richard, presently one of the most distinguished scholars of Franco-American history, for a presentation on credit unions. That insightful talk was also recorded for future viewing.

Now, for today’s main dish. I’m pleased to say that I recently finished compiling debates on emigration held at the Quebec legislature from 1867 to 1880. The debates of the Quebec legislative assembly and legislative council are available online, but the search function is imperfect and they are not segmented by topic. As a whole, parliamentary debates on emigration (and on such related issues as repatriation and colonization) remain an underutilized source. Perhaps it is because any effort to hold back the tide of migration seemed hopeless towards the end of the nineteenth century—or perhaps yet because public measures seem, in retrospect, too timid or unfocused.

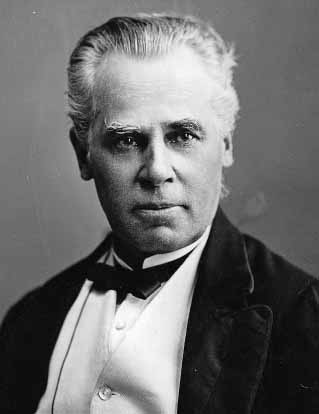

But it is important to look beyond the emigration reports of 1849 and 1857 and to consider what was and what wasn’t possible for nineteenth-century governments from the standpoint of economic opportunity and migration. Could elected officials and policymakers in Quebec City and Ottawa have done more to prevent the mass exodus? Were they happy to simply let the “rabble” go, as George-Etienne Cartier is alleged to have stated? What prevented bolder action? Ideology, budgetary constraints, a misunderstanding of farmers’ circumstances?

The compiled debates do not provide the ultimate, final, and definitive answer to these questions—but answers they nonetheless provide. Below are excerpts that provide a small glimpse of the exchanges in the halls of the legislative assembly. Those wishing to know more about the political circumstances of the time may want to consult my recent Twitter thread on nineteenth-century Quebec premiers.

Anyone interested in receiving a copy, in searchable PDF, of these debates can reach out to me either by using my contact form, by commenting below, or by communicating with me on social media or via e-mail.

George-Etienne Cartier, 1867:

Notwithstanding the drain of emigration natural to all Northern peoples, he [Cartier] thought we had contributed very large quotas of population to every portion of the American continent, our home population had vastly increased during the last hundred years, and that ought to reassure us. The outflow of our population depended in a great measure upon the desire of change, a spirit of adventure and other uncontrollable causes, as much as upon any defect in our industrial economy . . . he [Cartier] believed that we were on the eve of great progress and manufacturing enterprise. We were now four millions of people, whose interests would become identical and who would afford a market for the consumption in our local manufactures. In the City of Montreal, he had already seen a wonderful increase of manufactures attributable, in a great measure, to the great increase of population in that area.

Pierre-Samuel Gendron, 1868:

You will say that those who emigrate are leaving with the intent of also leaving agriculture and working in factories. This is true. But why do they abandon the way of life in which they were raised? Are they disgusted with it? No, we do not abandon the ways of our childhood; it happens by necessity. Those who leave can no longer live from agriculture, and they leave it with regret. If the issue is that some find it impossible to settle new lands, then we must conclude that we have to encourage the establishment of factories in our midst . . . While recognizing that agriculture must always hold the first place of importance and constitute the primary concern of government, we cannot but admit that a country such as ours would be strengthened by well-organized manufacturing. Let us encourage agriculture, colonization, the creation of factories, and emigration will cease.

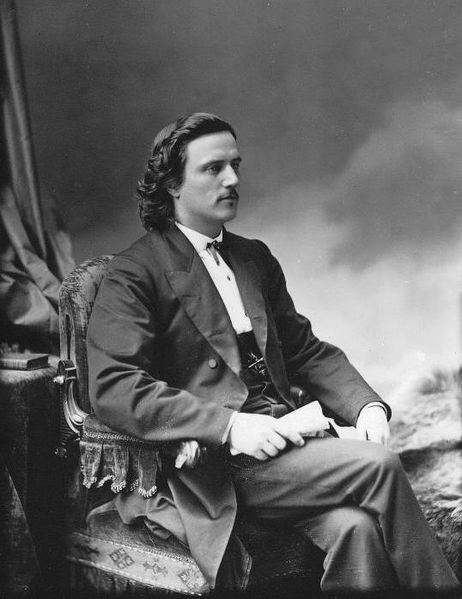

Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, 1869:

Ask our compatriots on the other side of the line why they have left their country, their village, their family. There’s no income to be had, they will say. No income! But why? Because the country isn’t as industrialized as it should be. It is in vain that some will say that Lower Canada [Quebec] is essentially agrarian; that is a mistake. A country that has six or seven months of winter is not and cannot be essentially agrarian. Build factories and you will utilize that half of the year that the farmer loses almost wholly. Build factories and you will retain those who do not care for agriculture. Build factories and you will enable the hard-working young man to amass savings and then face the perils of the forest. You will say that the manufacturing sector is of the central government’s jurisdiction; yes, for the commercial duties it collects—which by the way should be higher. But we should not remove manufacturing from the benefits of indirect, provincial protection through financial inducements…

Henri-Gustave Joly, 1873:

The honorable premier has willingly acknowledged that there is emigration to the United States, and yet, the Opposition was laughed at when it raised this issue in 1867. I have read all of the speeches from the throne and this is the first time that I find a word on emigration. I have to say that this is coming a little late, now that our compatriots are starting to return. If the government had addressed the issue before today, it would be truly ready to aid those repatriates and to keep them here. Rather than speechifying for the last six years, it would have done much more by recognizing this malady.

François Langelier, 1874:

The government promises measures to aid in the repatriation of our compatriots in the United States as well as foreign immigration. I do not know what these measures are, but surely I will not be proven wrong if I say that they will be ineffective and will produce nothing but useless expenditures. The past says something of the future . . . Why should Quebec not lead other provinces in Confederation rather than finding itself in last place? Why, instead of seeing immigrants teeming on our shores, do we find our own compatriots leaving for foreign lands? It is because agriculture is not receiving all the aid it should expect. As long as this situation persists, it will be in vain that we try to repatriate our people. Having returned, they will again face all of the challenges and difficulties that forced them to leave in the first place. As for foreign immigrants, once we have brought them here at great expense, they will move on to the United States, and there they will write back to their kin in Europe, warning them against Canadian immigration agents.

My John F. Kennedy and the Politics of Faith is available from the University Press of Kansas. Consider buying from the publisher or supporting your locally-owned bookstore.

Leave a Reply