This is the second part of an essay on nineteenth-century emigration reports. Please find the first half here.

In retrospect, the great demographic hemorrhage that weakened Canada in the 1840s might come as little surprise. There was a clear disparity between available labor, at a time of tremendous population growth in the St. Lawrence River valley, and access to land or non-agricultural work. We may wonder if this precarious situation owed to the Lower Canadian legislature’s decision to forego major infrastructure and development spending in the decade up to the Rebellion of 1837. Though that may be, pre-Rebellion policymakers could not predict the agricultural transition, the depressed lumber trade, on-going ethnic tensions, the troubled recovery from the Rebellions, and the political resistance of the éteignoirs that would together mark the 1840s.

The appointment of another special committee in 1857 indicates that even if many of these issues receded, emigration was a force of its own in the 1850s. It required a new look. Thus the legislative assembly of the Canadas nominated Joseph Dufresne from the riding of Montcalm and fellow committee members to study,

1st. Whether or not any emigration from Canada to the United States of America or elsewhere, has taken place during the last two years?

2nd. If such emigration has taken place, to what extent?

3rd. To investigate the causes which have occasioned it?

4th. To ascertain the most efficient means to adopt, to put a stop to such emigration.

The mandate was similar to that of the prior committee; again dozens of local observers would be recruited into this fact-finding mission through lengthy questionnaires. The results would be almost identical to those of 1849.

In 1849, for instance, the Chauveau committee thought it was entirely natural for those living in a “sufficiently peopled” country with limited opportunities to move abroad. Rather than pose a burden, emigrants became “founders” of new communities elsewhere. But this hardly applied to Lower Canada, “a portion only of whose territory is in a state of cultivation.” In 1857, Dufresne and his peers wrote,

When an ancient people become, by a redundant increase of their numbers, as compared with the extent of territory which they inhabit, confined and ill at ease in their native land, the emigration of a portion becomes a blessing to all, and not only to the country which the emigrants leave behind, but also to that new land, to which they bend their steps, and to the species in general.

But when a people still in the early youth of their national existence, weak in numbers, though distinguished for sobriety and hardihood, inhabiting a vast territory of an extent and fertility sufficient for the residence and abundant support of fifty times their number, abandon their homes, emigration is an evil, a public calamity to be deplored, and, if possible, averted. An exodus like this, without legitimate cause, must of necessity be the consequence of a radical social defect, which it is the business of society, to detect, and, if possible, to cure, by the application of timely remedies.

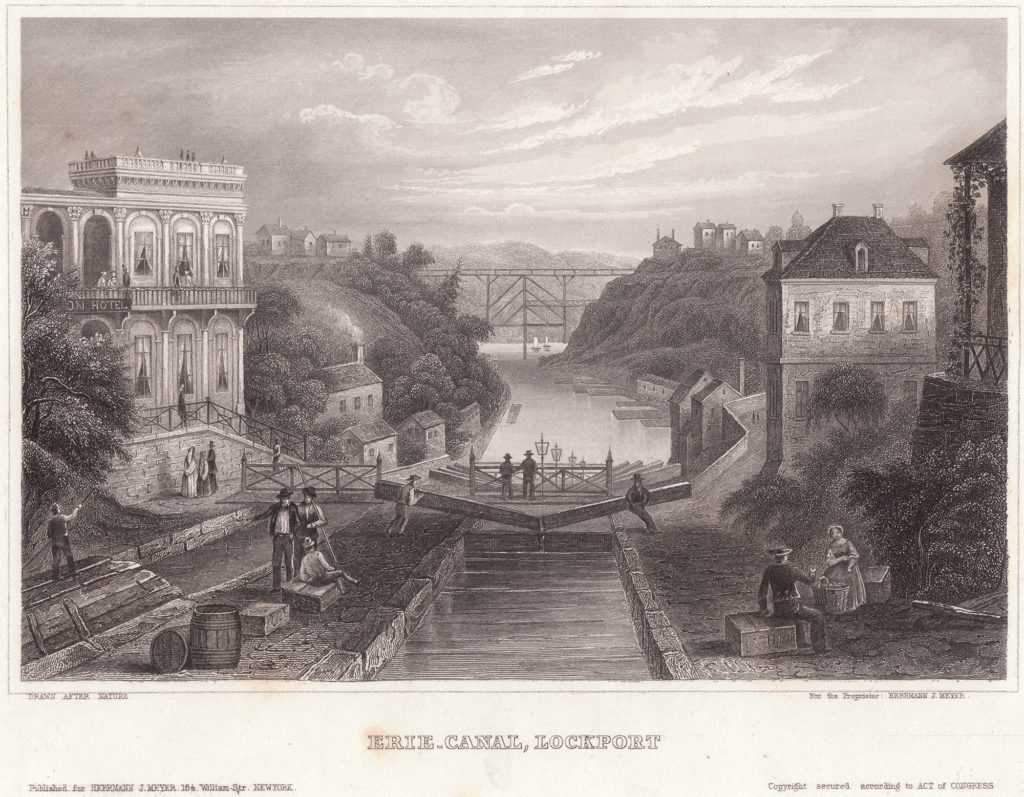

Again, the Rebellions were identified as a turning point by virtue of the “terror” that shook Lower Canada and its economy. (The focus here too was on French Canadians.) But the committee still could not ignore the relative advantages of the United States, including “[t]he regular employment, supplied by extensive public works, canals, railroads, &c., the rapid improvement and increase of all manufactures in the Eastern States; the reputed richness of the soil of Michigan, Illinois and other Western States.”

Alas, there was little discussion of the richness of Canadian soils outside existing settlements. As for industrial development, the committee seemed at first to have only contemplated factories as a way of decreasing wintertime unemployment. But the recent inauguration of the Grand Trunk Railway’s main line signaled benefits of a broader rail policy; the tariff might be adjusted to ensure the equitable trade of manufactured goods with the United States, thus protecting in some measure nascent Canadian industries. Still, identifying farmers’ sons as “the most useful class of society” and “the hope of the country,” the committee focused its work on improving agricultural conditions.

Little could be done with the natural increase of population in the “old settlements,” or yet about chain migration resulting from “attractive and seducing descriptions of [migrants’] new position [abroad].” On the other hand, one significant issue concerned communication and transportation to peripheral settlements and Crown Lands. As one Mr. Marquis put it,

Without roads no colonization is profitable. The most magnificent speeches of distinguished orators at Montreal and Quebec, and the pompous reports of meetings at which active presidents, honorary presidents, vice-presidents, corresponding committees, and treasurers, (save the mark!) who have no funds to manage, are appointed, are buried out out [sic] of sight in the first mud-hole which the settler falls in with on his way; all the finest words in the language of eloquence are then of less importance to him than one poor acre of corduroy road.

On agricultural conditions, the committee added:

The deficiency of the harvest for several years past, arising from the ravages of the Hessian fly, the rust in wheat, and the potatoe rot, as well as from the system of culture followed by our farmers. Your Committee are happy, however, in being able to remark that the passing of the law in the last session of Parliament for the encouragement of Agricultural Societies will soon have the effect of changing that system for one of progress, which will no doubt have a powerful effect in preventing emigration.

Dufresne and company asked the legislature to pick up former Crown Lands commissioner Joseph-Edouard Cauchon’s proposal for domestic colonization. They also returned to one of the contentions of the prior report: that property had its duties as well as its rights.

Provision should be made, by law, for the protection of the poor settler against the grasping ambition and the covetousness of the great land owners. Your Committee cannot but express their regret that the Bill passed by Your Honorable House in the present session, providing for the protection of both parties, in their respective rights of the latter as proprietors, of the former as de facto possessors and bona fide occupiers, has not received the sanction of another branch of the Legislature.

Ownership of large tracts of land ought to be a matter of public record, which might involve the “compulsory registration” of land grants. Proprietors, the committee also argued, should not displace settlers who have improved the land, or hold a lien over tenants’ timber.

In short, the report of 1857 constituted another well-meaning effort to address the economic woes facing the Canadas, especially Lower Canada. It is especially noteworthy in that it had little of the moralizing tone that would appear in the works and speeches of later opinionmakers. Although warning emigrants of the disease and destitution that might await them abroad, these two early reports on emigration did not indict the expatriates as moral failures or betrayers of the homeland.

What few measures had come to be since 1849 had, evidently, failed to halt mass emigration. Such would be the story of the subsequent half-century. A short-lived program of repatriation in the 1870s and the Conservative government’s National Policy seemed promising, as the depression of 1873-1877 shook the United States’ industrial establishment. But, before long, the tide of emigration resumed and again some could see in Canada a sick nation. The remainder of the century marked the apex of French-Canadian migration to the U.S. Northeast.

Interested readers may also want to consult a non-governmental report on emigration titled Le Canadien Emigrant ou Pourquoi le Canadien-Français quitte-t-il le Bas-Canada? Twelve missionary priests signed and issued this relatively brief manifesto in the spring of 1851; it is available in its entirety on Google Books.

Source

Report of the Special Committee on Emigration, Appendix to the Fifteenth Volume of the Journals of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada. 3rd session, 5th Provincial Parliament of Canada. Printed by Order of the Legislative Assembly. Toronto: Rollo Campbell, 1857. Canadiana.

Leave a Reply