They are a people with no history, and no literature.

With those words, among the most quoted of his infamous report, Lord Durham hit a sore spot. But, as certain well-placed families in Lower Canada acquired capital in the 1840s and 1850s, they secured not only the political influence of French Canadians but their cultural legitimacy as well. They seemed to agree that the proof of a people is in the writing. From Octave Crémazie’s bookstore to Les Soirées canadiennes and Philippe Aubert de Gaspé’s magnum opus, the turn of the 1860s marked the true beginning of a littérature nationale in Quebec. Through the following decades, many young, middle-class men would aspire to join Crémazie in national esteem and do their part for the cause of French-Canadian letters.

Thus, as early as 1880, the great poet Louis Fréchette could allude to the great rush of talent that had come during his lifetime. With their families depending on government patronage, nearly all of these figures had called Quebec City home.

Si nous remontons à la génération qui nous a précédés, j’aperçois Petitclaire, Parent, Soulard, Chauveau, Garneau, L’Ecuyer, Ferland, Barthe et Réal Augrs [sic], ces pionniers de l’intelligence, qui dans l’histoire, la poésie, le théâtre et le roman, ouvrirent, une si large trouée à la génération qui suivit. Plus tard l’Abbé Laverdière, Casgrain, LeMoine, Fiset, Taché, Plamondon, La Rue, et le premier d’entre tous, Octave Crémazie, viennent à divers[es] époques continuer vaillamment l’œuvre de leurs devanciers, pour faire place à leur tour à la brillante phalange contemporaine qui, à la suite de Lemay, de Fabre, de Bégin, de Routhier, d’Oscar Dunn, de Faucher de St Maurice, de Buies, de Marmette, de Legendre, s’est chargée de la glorieuse tâche de conserver au vieux Québec son titre si légitimement conquis d’Athènes du Canada!

These were exciting times. Young people were fashioning their heritage into exciting projects and lending their own inflection to French-Canadian culture. But the development of a national literature seldom happens without violent clashes over values, themes, language, and even basic grammar—to say nothing of the clash of egos. It is no easy matter, from available evidence, to trace the roots of the frictions that grew in the 1870s. Resentments were likely whispered long before they appeared in the press. But, by 1877, teams had coalesced and they were ready to enter the ring.

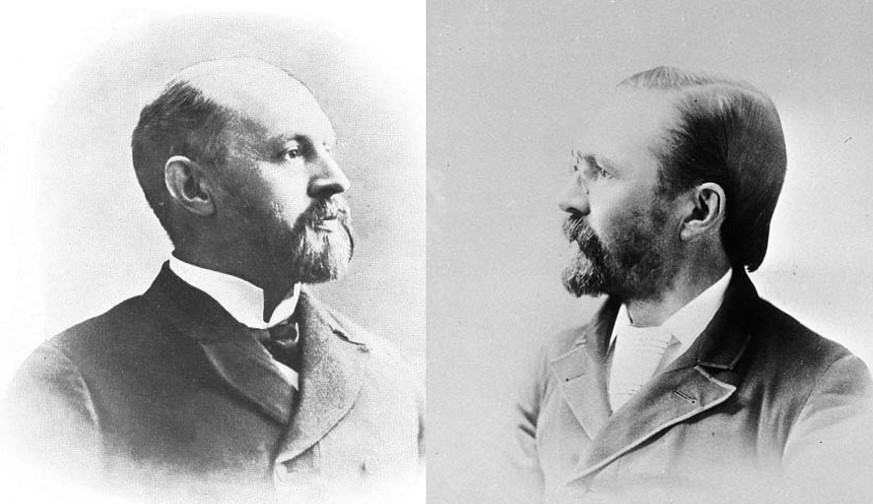

In one corner stood the tag team of Marmiche and barbiche, the diminutive Joseph Marmette and the dramatic Faucher de Saint-Maurice—stars of Quebec’s literary stage. Now largely forgotten, Marmette was the leading novelist of the 1870s. He and Faucher, a future member of the legislative assembly, were part of the small circle that gathered in Prosper Bender’s living room every Sunday.

In the other corner, facing them, was the man with the unrepentant pen, the president of Quebec City’s Institut canadien, monsieur J.-O. Fontaine. With him stood the original Kentucky headhunter, the repository of Truth (that is, the eventual founder of La Vérité) and the man who exceeded all new converts in zeal, Jules-Paul Tardivel.

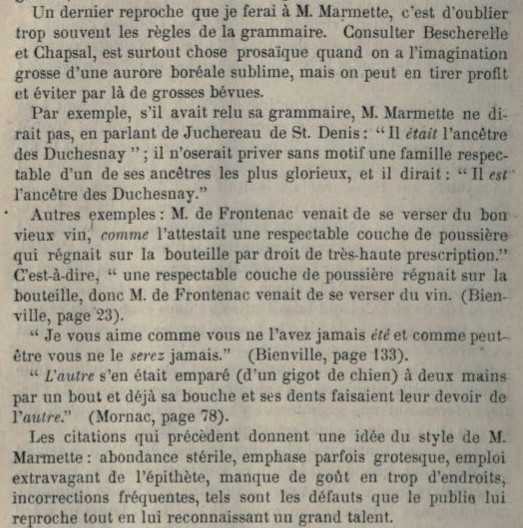

Landing the first blow was Fontaine who, in July 1877, wrote a scathing critique of Marmette’s work in La Revue canadienne. Fontaine acknowledged the strengths of his counterpart’s novels, but, by their brevity, those remarks seemed half-hearted. He argued that when Marmette was not emulating the style of a Walter Scott or James Fenimore Cooper, he fell prey to bad taste. The novels were weighed by florid descriptions and—le coup de grâce—poor grammar. Marmette had apparently failed to consult his Bescherelle. Fontaine offered dubious examples. For French speakers, the following gives a sense of Fontaine’s tone and approach.

Fontaine doubled down in a second piece. He attacked the entire novelistic enterprise: fiction writers painted vices and evils in a seductive light and led unsuspecting readers astray. (Tardivel shared his friend’s outlook but eventually penned a novel of his own.) Fontaine again dissected Marmette’s grammar, though what he deemed bad French was, in the examples he offered up, perhaps more a matter of stylistic preference.

Was this, then, a matter of bad faith on Fontaine’s part? Was Fontaine a gatekeeper? Or was Marmette a poor writer who did not deserve to be placed—whatever Fréchette might say—alongside Crémazie and Lemay?

Tellingly, of the novels Fontaine was reviewing, the most recent had appeared four years earlier. He was hardly informing a discerning public about the strengths and weaknesses of a forthcoming publication. On the other hand, Marmette’s Le Tomahahk et l’Epée had appeared earlier in 1877, and the Revue canadienne articles may have been a way of deterring interest in this latest novel—or lamenting, maybe in vain, its influence. By then, the provincial board of education had announced it would purchase Le Tomahahk et l’Epée for distribution alongside works by Faucher, Dunn, and others.

Indirect access to Quebec government favors spoke to a larger issue. Marmette was the son-in-law of Etienne-Paschal Taché, a former prime minister of the United Province of Canada. Bender’s sister had married one of Taché’s sons. Dunn, who was part of their coterie, was likewise related to the same family. This privileged access to power was addressed openly in the 1880s when Tardivel, writing under a pseudonym, argued that Faucher and friends were organizing as a colonization society simply to travel to the mother country on taxpayers’ dime.

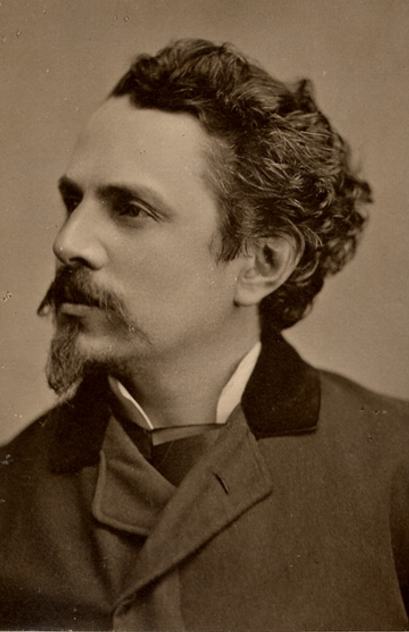

Tardivel quickly jumped into the fray on Fontaine’s side. In 1878, he explained, “I was raised among the Irish and when I see a row, literary or otherwise, the appeal is irresistible. I join the battle without waiting to be invited.” Through his long career as a columnist, Tardivel would be consistent in this regard.

And so, in the fall of 1877, once Marmette had responded to Fontaine and accused him of bad faith and malice, Tardivel defended the critic. From his pulpit at Le Canadien, he explained that “one need not have composed four or five novels of average interest, questionable utility, and dubious morality” to judge literary works. Marmette responded once more and, after justifying the timing of his answer, stated plainly that Tardivel’s disapproval came as no surprise. This dismissive response was, by the standards of the entire controversy, taking the high road. It marked the beginning of a public truce that lasted through the winter.

Both parties reentered the ring in April 1878 and this battle royale would last to the end of the year. This time, the spark was a ferocious review of Eudore Evanturel’s poetry, which, the reviewer stated, merited comment only because the book had the support of Marmette. That reviewer, writing as “Lysippe,” was neither Fontaine nor Tardivel. Feeling personally attacked again, however, Marmette blasted both of them in his attempt to unmask the man with the poisoned pen. The affair blew up far beyond the previous year’s confrontation.

The punches, feints, and blocks are too many to discuss here. But as we try to make sense of the stakes, we should notice the felicitous expression that Tardivel used in 1877 and revived the following year: he was battling the société d’admiration mutuelle—the mutual admiration society. The group around Marmette and Faucher had recognized the collective nature of the literary enterprise. They supported one another and nurtured the talent that came in their wake, the Evanturels of the world.

By contrast, once tagged by Fontaine, Tardivel rested his hopes in no one but himself; he jealously guarded his influence and visibility. Combative, he also saw himself as the protector of certain orthodoxies that helped steady him when attacked. Though it never came out in the papers as such, Tardivel was an ultramontane (both he and Fontaine belonged to the Cercle catholique) battling la bohème de Québec. In the spring of 1878, literature, ideas, and lifestyles gave way to personalities. It might be that good grammar had all along been but a pretext for settling scores.

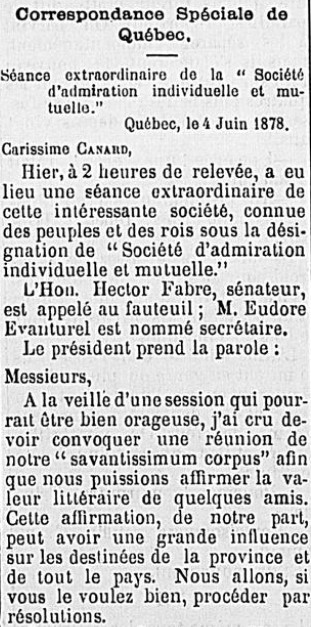

In early June, after weeks of public exchange, the Montreal-based satirical newspaper Le Canard skewered both sides. It imagined an “extraordinary session of the Société d’admiration individuelle et mutuelle.” The entirety of this mock session consisted of members recommending one another for honors. Hector Fabre moved that Fréchette be named the greatest poet of modern times. Jacques Auger proposed Arthur Buies as the greatest living prose writer. Fréchette then stated that Fabre was the greatest modern columnist, Evanturel his fondest discriple, and Tardivel a mean man.

The biggest risk that Tardivel took was not to defy this unofficial société, but to engage in creative writing by publishing a short travel narrative, “De Québec au lac à Jacob,” in 1878. As Faucher put it, Tardivel “came down modestly from his pedestal to sit with the humble.” It would now be for others to play critic. Faucher relished the role. In a two-part review published in November, he put his opponent through the same ringer that Marmette had suffered the year prior. The tone was similar; he highlighted seven grammatical errors Tardivel had committed in one short section of his essay. The author, Faucher added, “cultivates pleonasms more successfully than he handles spelling.”

Having tended to the dirty work, Faucher addressed the more substantive issue. He explained what this supposed société d’admiration mutuelle, the small group of writers that Tardivel assailed, was all about.

The mutual admiration society does not exist in the sarcastic sense suggested by the leader of the lac à Jacob literary school [Tardivel]; but the few names he has occasionally dared to give to the public as belonging to this coterie are of people who write, nourish the arts and sciences, study and ceaselessly seek all that can elevate the soul and the patrie [homeland]. These individuals have one goal—which is not to be disparaged—and are much more modest than Tardivel’s talent and school would grant. They work towards that which strengthens our beliefs, tightens our national bonds, and secures our institutions. Their ambition is to continually remind the French-Canadian nation of the greatness in its past, and all of the greatness that may lie in its future.

Naturally, this did not end the controversy. By this point, too much was on the line—not just the soul of French Canada, but egos. Neither side would concede the fight. In fact, the controversy spread to the English-language press when an author writing as “Timothy Tickler” (later “outed” as Prosper Bender) endorsed Faucher’s claims. Tickler argued that in a young country, criticism should not, by its tone and approach, be such as to deter literary creation. Writers and critics alike ought to foster native talent.

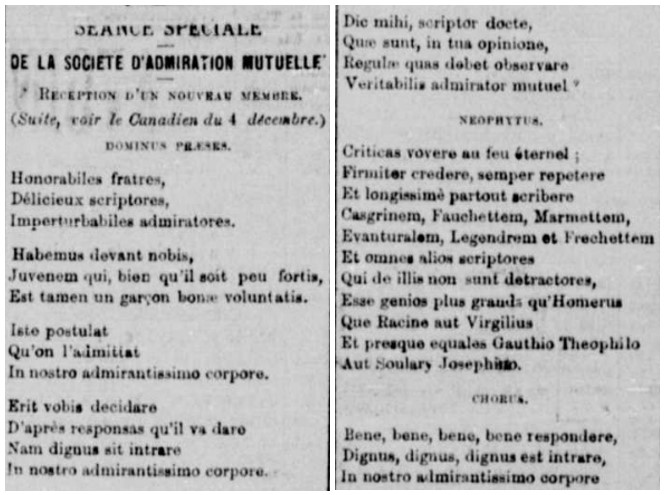

Tardivel borrowed a page from Le Canard and had his turn imagining the proceedings of the société. This time, Faucher was chairman and Bender was up for membership thanks to his contribution to the Morning Chronicle.

The real Faucher, Bender, et al. responded early in 1879 by collecting the many critiques of Tardivel’s written work in a small pamphlet. More attacks came during that year. By then, it had become clear that there would be no knock-out punch; each side retreated to its corner. When proposals for a Quebec academy of letters (similar to the Académie française) surfaced in 1880, one observer opined that good will and bonne entente would be impossible with the likes of Fontaine, Marmette, Tardivel, and Faucher in the mix.

The members of the unofficial société slowly went their separate ways, geographically and professionally, in the 1880s. Only Fréchette and Tardivel continued using the expression in public forums. By that point, both had become ideological lightning rods—the first, said to be a dangerous liberal freethinker, and the second, the most uncompromising of ultramontanes. The fracture of ideology should not, however, conceal how personal the fight had become.[1]

* * *

If Quebec’s literary market is small today, we can imagine what it was like 150 years ago. So, the whole conflict might seem like inside baseball from the standpoint of the average Quebecker d’alors. On paper, however, the stakes were high, for at issue was the fate of a distinct French-Canadian literature and the French language in North America. How would that national literature be written? In what style and by what standard? By whom? In the moment, this last question seemed to dominate all others.

Just as Franco-Americans have experienced ambiguous cultural relations with Quebec, French-speaking Quebeckers had to navigate the presence of metropolitan French models in their literature in the nineteenth century—and balance a desire to emulate Victor Hugo with their distinct realities. Their letters were, arguably, in a precarious position and not quite earning the outsider recognition they merited. In retrospect, it made sense to give creators a wide berth rather than stifling new initiatives by writing off entire genres and reducing art to inflexible grammatical standards.

But the real problem, of course, was unrelated to the quality of Marmette’s work—or any other person’s, for that matter. This whole piece could be subtitled “How to Bungle a Cultural Revival,” and the answer would be ego. (This is far from the first example on this blog.) Though hardly in a position of power, Fontaine and Tardivel sought to act as gatekeepers. They would sooner control the conversation by banishing works that did not meet their narrow mold than allow the experimentation that might lead in unexpected directions, far beyond the narrow, smoky offices of Le Canadien.

Sources

An exhaustive list of published articles written by or about our four contenders would be as long as this post. Beyond the links in the text, a good starting point for a general overview is Roger Le Moine’s classic biography of Marmette. See also Pierre Rajotte’s article on literary circles in the Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française (1997). The Dictionary of Canadian Biography includes biographies of Faucher and Tardivel and the site of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec remains the best gateway to their extensive body of work. Anyone looking for specific references for the articles mentioned above should feel welcome to reach out by commenting below or using the contact form.

[1] The resentment remained palpable in the early 1880s when many of Faucher and Marmette’s friends and acquaintances were selected as the initial slate of Royal Society of Canada members. With Faucher being one of the governor general’s advisors in the formation of the RSC, we shouldn’t be surprised that he and his pal made the cut while Tardivel did not. By no means did this ease tensions.

Leave a Reply