An earlier version of this essay appeared in the spring 2021 issue of Le Forum, the quarterly publication of the Franco-American Centre (University of Maine). Please cite appropriately.

* * *

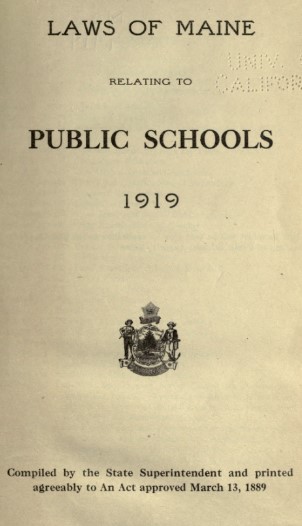

…provided, further, that the basic language of instruction in the common school branches in all schools, public and private, shall be the English language. Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit the teaching in elementary schools of any language as such.[1]

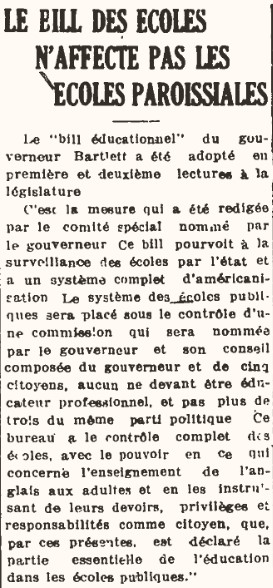

On April 1, 1919, Governor Carl Milliken of Maine signed into law a bill authorizing the state’s superintendent of education to enforce English-language education in public and private schools.[2] This assimilationist measure would hit all minority language groups in Maine equally. As the largest of these groups, however, Franco-Americans had special cause to be aggrieved and to feel targeted.

We can imagine the uproar when Milliken proposed this measure at the opening of the Seventy-Ninth Legislature three months earlier.[3] We can imagine the Franco-American elite forming committees, drafting petitions, and marching Maine’s French-Canadian and Acadian communities into the fight for their cultural survival. In the prior decade, it had done exactly that to remove parish property from the control of the Catholic bishop of Portland, Louis S. Walsh.

We can imagine the Association Canado-Américaine (ACA) and the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste (USJB) drawing attention to the issue and raising funds across the region. Quebec newspapers would have joined the fray and insisted on the cultural threats standing before expatriates in the United States.

We can picture it now. But our mind’s eye—informed by a tale of endless cultural and religious battles—has betrayed us if this is the image we are forming.

While many present-day Franco-Americans are aware of this bill and its effects on their cultural survival in Maine, the circumstances surrounding the bill’s inception and enactment are murky. Surprisingly, landmark works penned by Adolphe Robert and Robert Rumilly in the 1940s and 1950s—works that closely mirrored the records of the ACA and USJB—made no mention of an organized struggle against assimilation in Maine in 1919, unless we count Rumilly’s cryptic reference to Walsh’s stance on education.[4]

In more recent Franco-American historical syntheses, the education bill of 1919 usually earns a few sentences meant to corroborate other evidence about forced Americanization in that era. These books almost all cite another secondary source, and with reason: primary evidence of Franco mobilization against the bill is scant.[5] Why this is so deserves greater consideration.

Background to the Bill

The Maine legislature passed the English-language education bill less than six months after the end of the First World War. In the prior two years, concerned about immigrants’ commitment to their adoptive country, the federal government had closely monitored and sometimes censored the foreign-language press. Through the Committee on Public Information, it had also launched propaganda campaigns aimed to foster “one-hundred-percent Americanism.” Loyalty to the United States was defined in increasingly narrow cultural terms. At war’s end, a new threat appeared on the horizon: radical elements—no less foreign—aligned with the Bolsheviks. The country was entering the Red Scare; an exclusive nationalism was still the answer.[6]

To foster “Americanism,” state legislators introduced English education bills across New England. In 1919, asserting the bona fide patriotism they had manifested during the war, Franco-Americans strongly denounced the measures put to the Massachusetts and New Hampshire legislatures. Historians have studied these struggles and revealed that French speakers were not cowed into complete silence during Americanization campaigns. But what of Maine?

Biddeford’s French-language weekly newspaper, La Justice, made no mention whatsoever of the education bill. More research will determine whether Lewiston’s Le Messager devoted more attention to the education debate than its counterpart in Biddeford; other Lewiston newspapers evince no groundswell of Franco-American activism in the city. Of the petitions submitted to the legislature in February and March in protest of the English-only law, not one originated in Biddeford or Lewiston. In Nashua, New Hampshire, L’Impartial carried articles on the education battle in its own state and in Massachusetts, but none on the situation in Maine. Surely it would have taken note of ferocious protests in the Pine Street State—had such protests materialized.

The bill on English instruction was largely buried in the record of legislative business reproduced by Bangor’s Daily News. Evidently, for English speakers of central Maine, this was not a hot-button issue—a means of stoking patriotic fervor, or cementing their support for the Republican Party. But neither was it a carefully kept secret to be sprung on unsuspecting minority groups at the end of the legislative session.

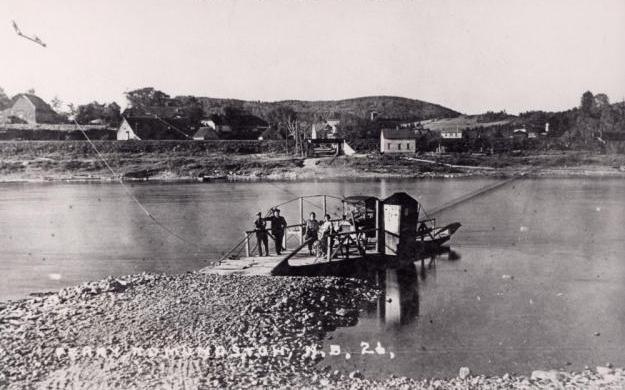

For one thing, there were acts of protests prior to the enactment of the bill. House members from Aroostook Country introduced petitions from Madawaska, Fort Kent, Caribou, St. Agatha, Van Buren, and other towns and villages, all contesting the bill.[7] Contemporary newspapers made much of the fact that the postmaster of Fort Kent, Irénée Cyr, who had previously served in the House, traveled 300 miles to testify before the Committee on Education in February. The St. John Valley French were leading the charge against assimilation.[8]

The Aroostook petitions only add to the puzzle. What would explain relative silence in Biddeford and Lewiston?

A Partisan Issue?

Electoral politics may help to elucidate the issue—to an extent. Although willing to support Franco-Americans on the Democratic ticket, La Justice had a record of endorsing Republican candidates. It had welcomed GOP victories in the fall of 1918. Among those winners was Carl Milliken.[9] In light of the federal Americanization campaign and its own suspicion of the labor movement, the paper’s stance was not unusual. In 1919, editor Alfred Bonneau may have continued to back the GOP as a bulwark against radicalism and chosen to place education on the backburner.

In Lewiston, voters went to the polls to elect a municipal government on March 3, 1919. There, the Franco-American community was closely aligned with the Democratic Party; one of their own, Charles Lemaire, sought reelection as mayor on the Democratic ticket. The GOP put up a strong fight and came within a hundred votes of unseating Lemaire.[10] We may wonder whether Lewiston Democrats sought to avoid the education issue because it would have pushed a soft Irish vote to the Republicans.

Yet more likely was a sense of powerlessness among Franco voters. At the state level, Maine’s Republican establishment seemed unshakable. The exclusion of people of French-Canadian and Acadian descent became a vicious cycle. The Republican establishment’s record of Anglo-Saxon, Protestant nativism pushed Franco voters to the Democrats; seen as a captive electorate, these voters could no longer expect GOP outreach. (La Justice would in time change its colors.) Beyond their industrial bastions, Franco-Americans were relegated to a political wilderness.

In 1919, the State Senate had but one Franco-American member, a Republican from Lewiston. Six Francos sat in the House, all of them Democrats—two from the St. John Valley, two from Lewiston, one from Brunswick, and the last from Biddeford (Louis B. Lausier, then beginning a long and distinguished political career).[11] Aside from Fort Kent’s William J. Audibert, who introduced petitions, historians must struggle to find evidence of these legislators’ presumed public opposition to the education bill. Before the “silent playground,” there seemed to be silence of a different kind in the chambers and committee rooms of the state capitol.[12]

Questions and Interpretations

One prominent figure—far more influential than Irénée Cyr—did draw momentary attention to the bill. No stranger to the State House, Bishop Walsh appeared before the Committee on Education on March 5 accompanied by Peter Charles Keegan, the former member for Van Buren; Cornelius Horigan, the former and future mayor of Biddeford; and veteran and attorney Albert Beliveau of Rumford. All were Democrats.[13]

Walsh was primarily concerned about the extension of the state superintendent’s jurisdiction to private schools. The Catholic hierarchy in the Northeast was more worried about the slippery slope of growing state control of parochial schools than about anglicization. In prior hearings, Walsh had explained to legislators that the basic course of instruction in parochial schools was already in English. There is little doubt, however, that prior to 1919 subjects beyond the state-mandated course of study were taught in French in Franco-American parish schools.[14]

How did the man charged with enforcing the law view language? State Superintendent Augustus O. Thomas expressed remarkable openness when he testified before the Education Committee. The bill “does not prohibit the teaching of foreign languages,” he declared. “The foreign languages should be taught in the elementary school as they can be learnt easier at that time than at any other period of life . . . It is easy for French teachers to teach through the French language to children of French extraction English and it is about the only way it can be done.” Thomas declared that he “was willing to make any change necessary to safeguard the right and objects of the bill.”[15]

From such declarations and others, we might conclude that the primary object of the bill was not to banish other languages, but to ensure sufficient proficiency in English among minority groups. The time had come to bring unilingual island communities into the U.S. mainstream.[16]

One scholar asserts that after 1919, French-language instruction was illegal for fifty years in Maine.[17] There is no question, from the letter of the law and Thomas’s statements, that French could still be taught as a language. Historical misunderstandings occur on whether the bill could allow the teaching of other subjects in French. What, indeed, is a “basic” language of instruction, and would it be different from an exclusive language of instruction?

Some clarity comes from the equally symbolic moment when, in 1969, the legislature—with the notable support of Elmer Violette of Van Buren and Albert Beliveau’s son Severin—voted to permit foreign-language education in the first two years of elementary school. Violette’s remarks at that time are worth noting. “Thirty years ago,” he declared, “they were starting us in the French language [in grade school], and then on to English.” Only gradually, in the interwar period, had French disappeared from the classroom, Violette stated.[18]

In the 1930s, at Lewiston’s Ecole Sainte-Marie, Lucien Aubé did not encounter serious study in (or of) the English language until fourth grade. By sixth grade, pupils could expect half-day instruction in each language.[19] Michael Guignard adds that “in Biddeford parochial schools up to the sixth grade in the 1950s we had a half day of French; religion and bible history [were] in French, and then we studied French—grammaire, dictée, épellation et lecture!”[20]

Public v. Private

Historian Mark Richard explains that when they arrived at Sainte-Famille parish in Lewiston, in 1926, the Sisters of Saint Joseph (a teaching order) chose to limit French instruction to one hour per day in hopes of easing Franco-Americans’ acculturation. They felt pressure from Bishop Walsh to meet the spirit if not the letter of the education bill passed a few years earlier. Richard finds little resistance or opposition from Lewiston’s Little Canada to the Sisters’ decision—except from Le Messager, which remained committed to the half-day system.[21] “[T]he [1919] law did not apply to the elementary schools where the nuns taught,” Richard also writes.[22] The law spared parochial schools, but those under control of the bishop or of other teaching orders could not expect the same linguistic leniency.

But didn’t the bill state otherwise? It read, again, “that the basic language of instruction in the common school branches in all schools, public and private, shall be the English language.” This too has led to confusion. The same section of the state education code previously made reference to “private schools approved for tuition and attendance purposes” (seemingly eligible for state funds) and it may be that the private schools touched by the language clause were precisely those. It also happens that this section appeared in the duties assigned to the State Superintendent of Public Schools. All of this would point to the effective exclusion of parochial schools.[23]

In her recent doctoral dissertation, Elisa Sance highlights the different educational regimes that explain the responses of different Franco-American localities. Maine’s public education system was highly decentralized; its town-based structure meant that local trustees had considerable authority over what would be taught and by whom. In Aroostook County, predominantly French-speaking towns hired Catholic religious orders to run public schools where the French language was in an exalted position.[24] However, in industries cities—where they were most concentrated, more likely to pool resources, and under more assertive clerical leadership—Franco-Americans were less dependent on public schools.

The absence of a coordinated campaign in such places suggests that Franco-Americans there understood that their parish schools would remain untouched by the 1919 bill. They also seemed to willingly accept a two-tier system. Church schools provided instruction that matched French Canadians’ values and cultural aspirations; upwardly-mobile families seeking a mainstream English-based education for their children could send them to public schools. When the parochial schools and their teaching staff narrowed the amount of French instruction in the interwar period, this was not a matter of public policy, but an issue to be resolved within the Church.[25]

The St. John Valley French understood that their reliance on a publicly-funded school system meant that they would not escape “basic” education in English. This may have been the unspoken intent of the education bill, for there had been prior attempts to bring this borderland people into the great (English-speaking) American family through school reform. But through its concerns and acts of protests, the French population in this region would find itself without the support of downstate compatriots.[26]

The education bill proposed and adopted in 1919 captured the spirit of Americanism that swept through the country following the First World War—a spirit that had not yet seen its most extreme manifestations. Though various factors explain why Franco-Americans did not protest more vociferously in certain parts of the state, the key lies in the role of public and private schools. In this sense, the events of 1919 say as much about vastly different experiences within the Franco-American community as about the fracture between Anglo-Saxon Protestants and their French-Canadian and Acadian neighbors.

With special thanks to Michael Guignard and Camden Martin.

[1] Chapter 146, Acts and Resolves as Passed by the Seventy-Ninth Legislature of the State of Maine – 1919 (Augusta: Kennebec Journal, 1919).

[2] “Public Acts Signed by the Governor,” Lewiston Evening Journal, April 3, 1919, 6.

[3] Legislative Record of the Seventy-Ninth Legislature of the State of Maine (Augusta: Kennebec Journal, 1919), 26.

[4] Adolphe Robert, Mémorial des Actes de l’Association Canado-Américaine (Manchester: L’Avenir national, 1946); Robert Rumilly, Histoire des Franco-Américains (Montreal: Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste d’Amérique, 1958). The part of Lewiston’s Institut Jacques-Cartier, the city’s foremost Franco-American society, in the debates of 1919 remains unclear.

[5] Included here are the works of Gerard J. Brault, François Weil, Armand Chartier, Yves Roby, and David Vermette.

[6] We should note that this debate occurred before the second incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan had gotten any meaningful foothold in the region.

[7] Legislative Record of the Seventy-Ninth Legislature, 303, 322, 352, 392.

[8] “Language in the Public Schools,” Lewiston Daily Sun, February 27, 1919, 10; “Fort Kent Is Much Opposed,” Lewiston Evening Journal, February 27, 1919, 7.

[9] “Grande victoire républicaine,” La Justice, September 13, 1918, 2.

[10] “Lemaire Elected But City Government Is Republican,” Lewiston Daily Sun, March 4, 1919, 1, 10.

[11] Legislative Record of the Seventy-Ninth Legislature, 3, 8, 48-52.

[12] The term is borrowed from Ross and Judy Paradis’s essay in Voyages: A Maine Franco-American Reader, ed. Nelson Madore and Barry Rodrigue (Gardiner: Tilbury House, 2007).

[13] “Bishop Walsh Opposed Bill Relating to Public Schools,” Daily Sun, March 6, 1919, 1, 4.

[14] “Committee Hearings at Augusta Thursday – Educational Committee,” Bangor Daily News, February 7, 1919, 11.

[15] “Bishop Walsh Opposed Bill,” Daily Sun. More puzzling yet was a report in the Bangor Daily News stating that “there would be nothing to prevent parochial and private schools giving instruction in other languages, so long as they complied with the provision of the law.” What was the law’s purpose if not to institute instruction in English? See “Committee Hearings at Augusta Thursday,” Daily News.

[16] This is not to deny the presence of firebrands whose nativism was far less elastic.

[17] Susan Pinette, “Un ‘étonnant mutisme’: L’invisibilité des Franco-Américains aux Etats-Unis,” La jeune francophonie américaine: Langue et culture chez les jeunes d’héritage francophone aux Etats-Unis d’Amérique, ed. J. E. Price (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2017), 185.

[18] Legislative Record of the One Hundred and Fourth Legislature of the State of Maine – 1969 (Augusta: Kennebec Journal, c. 1969), 1495-1496.

[19] Lucien A. Aubé, “From the Parochial School to an American University: Reflections on Cultural Fragmentation,” Steeples and Smokestacks: A Collection of Essays on the Franco-American Experience in New England, ed. Claire Quintal (Worcester: Editions de l’Institut français, Assumption College, 1996), 639-640.

[20] Personal correspondence. Guignard adds, “I had known nothing about [the 1919 law] until the 1980s.”

[21] Mark Paul Richard, “From Franco-American to American: The Case of Sainte-Famille, an Assimilating Parish of Lewiston, Maine,” Histoire sociale/Social History, vol. 31, no. 61 (May 1998), 79-80.

[22] Richard, Not a Catholic Nation: The Ku Klux Klan Confronts New England in the 1920s (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015), 54.

[23] State Superintendent of Public Schools, Laws of Maine Relating to Public Schools (Augusta: 1919), 50, 52.

[24] Elisa Sance, “Language, Identity, and Citizenship: Politics of Education in Madawaska, 1842-1920” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maine, 2020), 103, 111, 170-172, 178. Also see Béatrice Craig and Maxime Dagenais, The Land in Between: The Upper St. John Valley, Prehistory to World War I (Gardiner: Tilbury House, 2009).

[25] Protests may have become unimaginable after the defeat of the Sentinellism in the 1920s.

[26] Sance, “Language, Identity, and Citizenship,” 106-107, 180-181.

Leave a Reply