Franco-Americans—and a larger community of French Canadians—were visible in 1921. This is the second part of a year-long tour of major stories concerning Quebec and its diaspora. See the first installment here.

May

All eyes turn to Manchester, New Hampshire, for a series of high-profile events. On May 11, Catholic residents celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Joseph-Augustin Chevalier’s appointment as pastor of the French-Canadian community of Manchester. Chevalier established the parish of Saint-Augustin and was the driving force in the building of numerous other Catholic institutions across the city (schools, convents, an orphanage, etc.). Religious services aside, the anniversary is marked by a giant banquet held at Villa Augustina in Goffstown and presided by Mgr. George Albert Guertin, the first Franco-American bishop. Chevalier, who was ordained by Bishop Bourget of Montreal in the 1860s, is still alive and well. During the multiday celebrations, Guertin ordains Adrien Verrette, the son of the Manchester mayor; his pastorate would also span generations—a symbolic passing of the torch.

For two days at the end of the month, the regional chapter of the Dames Forestières Catholiques meets and selects delegates to a national congress in Omaha, Nebraska. Finally, Manchester hosts the fourth annual congress of the Fédération catholique franco-américaine. This federation brings together the major mutual benefit societies of the Northeast: Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste, Association Canado-Américaine, Forestiers, and several smaller organizations. Among the eminent attendees are Hugo Dubuque and Edouard Montpetit—the former “mansplaining” the duties of Catholic women now that they have access to the ballot box. The outgoing federal council included J.-H. Guillet of Lowell; Pierre Bonvouloir of Holyoke; Henri Ledoux of Nashua; Adélard Archambault of Woonsocket; and many other well-known, distinguished Franco-Americans. The new executive council is led by Eugène Jalbert.

See La Presse, May 11, 1921 and May 31, 1921.

June

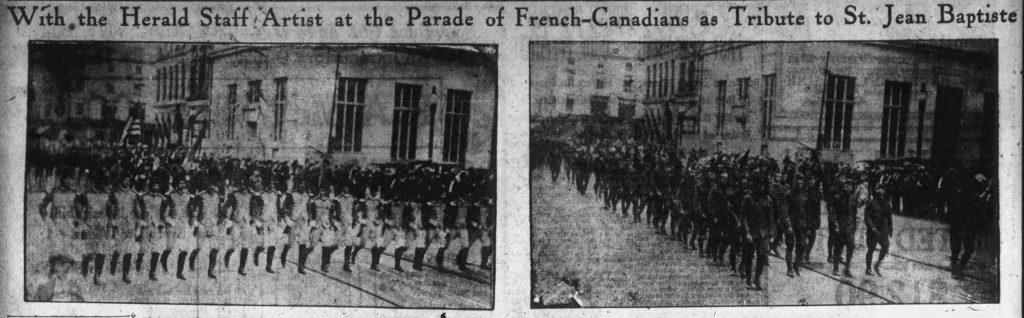

On Sunday, June 26, the Franco-Americans of Fall River enjoy a grand, belated feast of Saint-Jean-Baptiste organized by delegates of the main mutual benefit societies. The day begins—predictably—with a solemn high mass at the church of St. Anne and the community takes over the city in the afternoon with a “monster parade.” Some 3,000 people led by marshal Wilfrid Bessette march in the parade; the first group of marchers are veterans of the Canadian and American armed forces. A “division” of women and girls carrying small American flags is led by commander Melanie Bergeron. They accompany a float representing colonial icon Marguerite Bourgeoys. Altogether, the eight parade floats chronicle the development of French “civilization” in the Americas. Speeches at South Park follow the parade, and the singing of the “Star-Spangled Banner” closes the event.

Only a few days later, a Connecticut newspaper reports that many French Canadians are planning to take advantage of summertime slowdowns in production to visit friends and family in Canada.

See Evening Herald [Fall River], June 27, 1921, Fall River Globe, June 27, 1921; Norwich Bulletin, June 30, 1921.

July

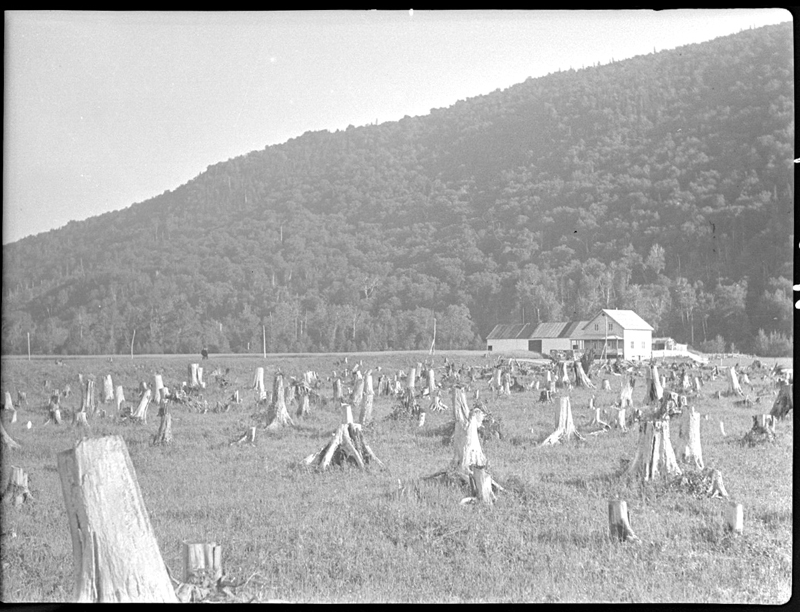

In Le Droit (Ottawa), columnist Harry Bernard highlights obstacles to the repatriation of French Canadians in the United States. This is again a pressing issue, as emigration from Quebec, which had decreased considerably at the turn of the century, has resumed at high levels in the wake of the First World War. Franco-Americans have had time to build institutions and become attached to the Great Republic. Bernard also recognizes that industrial opportunities are more limited on the Canadian side. Like generations of elites before him, he argues that surplus labor should be diverted to the Abitibi, Témiscamingue, and Lac-Saint-Jean regions of Quebec and to northern Ontario to develop the wilderness.

Five months later, an Oblate priest named Chabot has his turn in the same newspaper. He worries about Quebec’s loss of influence within the federation:

Have we considered the preeminent place we would today hold in the Dominion if all these French Canadians, instead of spreading across New England, had remained rooted to their [ancestral] land; if they had made the precious contribution of their arms, their talent, their spirit, and their heart to the development of our national energies and the triumph of our rights? Indeed, we would be masters in our own home [maîtres chez nous], rather than at the mercy of the strange principle that is numerical superiority. Alas, all of this is notably compromised.

Although the Great Depression and U.S. immigration restrictions enacted in 1930 are often cited as ending this last wave of emigration, it is in fact largely over by 1925.

See Le Droit, July 12, 1921 and December 5, 1921.

August

In 1921, Quebec moves towards a tighter control of the distribution of liquor, while the Ontario government bans the importation of alcohol into the province. Americans are already living with prohibition—and smuggling. On August 1, the Burlington Free Press reports that three men from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, “are safely lodged” in a Vermont jail after a police chase through the backwoods of Caledonia County. The men were attempting to bring 100 gallons of alcohol that they had stolen in Abercorn, Quebec, to Rhode Island. Though they changed the license plate on their Packard, police caught up with them. The men fled the car but were caught independently within the day.

Nearly three weeks later, a car loaded with whiskey that had eluded prohibition enforcement officials is seized in downtown Burlington. Its three passengers are all Canadians. They might have gotten away with their shipment were it not for the strong smell of alcohol, perhaps due to broken bottles, that emanated from the car when parked in a garage. The car is taken apart by the deputy collector for the district—who happens to be vacationing in Burlington—and agents pull out 70 quarts of whiskey concealed in the seats. This happens just as Joseph Roy, captain of the Pocomoke, is arrested in Atlantic City. Although Roy was ostensibly transporting a cargo of alcohol from the Bahamas to Quebec, U.S. officials believe his merchandise was in fact destined to Americans.

Unfortunately there is more to smuggling than booze cars and booze boats. In Montpelier, Vermont, Henry Tessier’s trial for human smuggling begins. Tessier, a Barre resident, was arrested in March and stands accused of bringing four Chinese men into the country in contravention of immigration laws. So does the principal witness, Georges Laporte from Knowlton, Quebec, who is awaiting his own trial. Thanks to a deadlocked jury, Tessier is soon out on the streets—and then again arrested on the same charge, with accomplice Carl Benway, in September.

Even if Canadian citizens can still move across the border largely unimpeded, prohibition and high-profile events like these contribute to the steadier enforcement of national spaces.

See Burlington Free Press, August 1, August 18, August 23-24, and September 9, 1921; New York Times, August 17, 1921.

Come back next week for Part III.

Leave a Reply