Thanks to digitization projects, it’s now easy to find major news stories about the French-Canadian community in the era of mass immigration—but also easy to overlook just how common those stories were. Such press coverage came in all sorts of forms and on a wide variety of issues. Newspapers discussed immigration, the challenge of acculturation in the United States, the political fate of Quebec, Franco-Americans’ community activities, and less consequential stories in the “if it bleeds, it leads” mold. Below is a small sample of the articles published a century ago. It’s a year-long tour d’horizon that raises the ways in which Franco-Americans—and a larger community of French Canadians—were made visible in 1921.

January

The stage production of The Storm, which began its run on Broadway in 1919, continues its tour across the nation and hits Minnesota. The play revolves around Mannette Fachard, a French-Canadian girl who is torn between two men, one a worldly but timid product of high society, the other a “primitive but honest” woodsman. The play earns praise for the special effects involved in the fictional storm that confines the three main characters to a wilderness cabin. In an earlier interview, lead actress Helen MacKellar explained that in The Storm,

I am a French Canadian girl and I use the patois of the north woods throughout. Of course, I learned French at school in Spokane and Chicago, but when I knew I was to have this part I realized my French was merely ‘schoolroom’ French and not what the critical ear would demand. So I spent a summer among the French-Canadians, and although it is impossible to perfect one’s self in that short time, I think I made sufficient progress to make my accent and use of the French-Canadian idioms passable.

The Storm is, in this era, one of many stage and film productions featuring French-Canadian characters. With the closing of the western frontier, audiences are drawn to the north and to the French and Indigenous peoples living in the mysterious Canadian wilderness. Across the United States, there is no escaping depictions of French-Canadian trappers, traders, and miners—portrayals that are sometimes one-dimensional but often flattering.

See New-York Tribune, November 9, 1919; Star Tribune [Minneapolis], January 23, 1921; Norwich Bulletin, October 16, 1922. Read more about such productions in the fall issue of Le Forum (University of Maine).

February

Two years after Maine’s enactment of an English-language education bill, certain lawmakers in Vermont aim to do the same with Bill 243. Although Vermont is a diehard Republican state where French Canadians occupy a political wilderness, opposition to this “Americanizing” measure is more public and even seems more widespread—perhaps precisely because the Canadians pose less of a threat. According to a local newspaper, that opposition comes in part from those who believe that parochial schools are doing good patriotic work.

During legislative hearings, one witness draws applause by “express[ing] the loyalty of the 5,000 French people of Winooski to the United States.” A monsieur Chevrier, also of Winooski, gains recognition for the naturalization classes that he has led and that have brought over 800 men to American citizenship. “Anglo” speakers also evince concern with the bill. One insists that before the bill can be adopted, there needs to be some evidence that disloyalty or un-American sentiments are present in Vermont; another fears that an assimilating measure like this one will turn away French-Canadian newcomers, some of whom “are putting the abandoned farms of northern Vermont on the map.” An editorial statement of the Barre Daily Times rejects the bill in its current form, for it would prevent the pursuit of bilingualism.

The following month, Rutland’s Father Vézina denounces a civil servant who claimed publicly that French Canadians are a threat to the state. That official is forced to backtrack and states simply that she hopes for an English-only education bill. Legislation of this kind does not pass in Vermont.

See Barre Daily Times, February 23, 1921; Rutland Daily Herald, March 22, 1921.

March

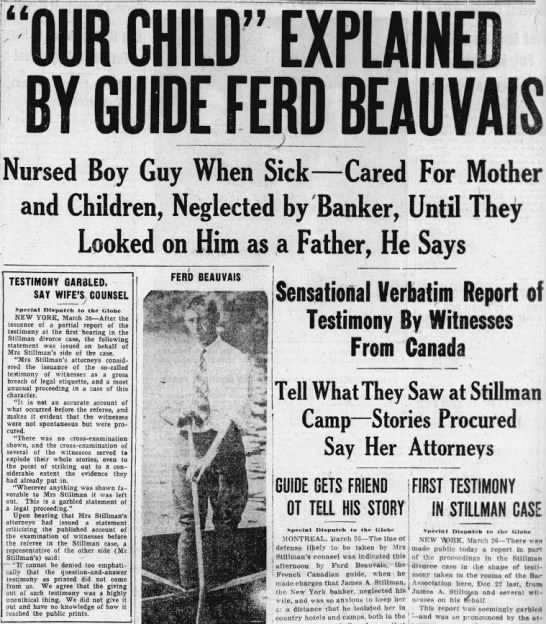

Hearings open in the Stillman divorce trial in New York City. The legal fight between “Fifi” Potter Stillman and her husband James Stillman, the millionaire president of a New York bank, is national news. At stake is custody of the couple’s two-year-old son, but also each person’s reputation and a heck of a lot of money. Mrs. Stillman demands over $100,000 annually in alimony and accuses her husband of neglect and infidelity; Mr. Stillman questions the paternity of their son. Because the Stillmans have a wilderness lodge in Quebec, north of Trois-Rivières, much of the evidence for each party lies with French-Canadian witnesses.

Canadians are brought to New York to testify about Mrs. Stillman’s relationship with wilderness guide Ferd Beauvais, who states that the financier did neglect his wife. Among those French Canadians are a nosy housewife, Hectorine Nanault Lafontaine, who hosted Fifi and Ferd and listened closely while they spent time with one another. The story could easily be drawn from a contemporary movie—and it is particularly interesting to see that the verdict in the most famous trial of the day rests with ordinary folks from the Mauricie. The trial and its witnesses hit the front page again in May.

See Boston Globe, March 27, 1921, and following issues.

April

What is the future of Canada? In the spring, Quebec Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau’s views on the subject, expressed in an address to the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Montreal, go viral. Taschereau envisions three different paths—political options that have in fact been circulating since the mid-nineteenth century. Canada can either join the United States, remain closely attached to Britain and the empire, or pursue full independence. The premier sees annexation to the Republic as the biggest threat to the survival of French-Canadian culture; it would entail speedy assimilation. The status quo is the better option. He considers Canada to be a nation and one slowly evolving towards independence, but what optimism he might have about this prospect is tempered by social divisions and the cost of nation-building borne by the eastern provinces.

See Daily News [New York City], April 26, 1921.

Come back next week for Part II.

Leave a Reply