In the colony’s earliest days, winter was an enemy.

It suspended communication with the mother country and brought agriculture to a standstill for six months. Early frosts imperiled the food supply; long winters raised, in the first years, the specter of famine and scurvy.

The settlers of New France at least benefitted from a seemingly inexhaustible source of fuel—in the guise of immense forests—and the experience of Indigenous groups. The colonists accrued their own knowledge, which, combined with religious traditions brought from France, cohered as distinct seasonal customs that persisted in some form for centuries. There were winter pastimes and periods of celebration. No less, this was an unforgiving season. To make it through half the year, families and communities had to work diligently and plan carefully through the other half. If winter could be a period of relative rest, the rise of the lumber industry in the early nineteenth century created a new set of dangers for the thousands of young men employed in logging camps.

Some time passed before the people of French Canada embraced winter specifically for leisure and sports or envisioned activities beyond the shadow of the parish steeple. The organization of a carnival, for instance, required modern infrastructure—railways and coherent urban transportation, hotels, and various amenities that could support a sudden influx of thousands of people. Ordinary people needed disposable income, however modest, to travel and attend events. Crucially, also, winter carnivals emerged with a rising urban middle class that could devote time to amateur athletic clubs and event planning.

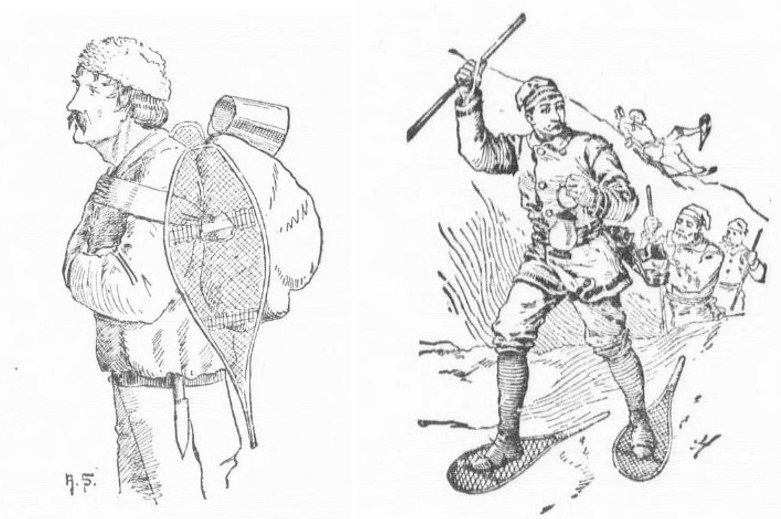

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, most of those conditions came together in the Province of Quebec. As organized “excursions” and railway fare discounts indicated, large-scale tourism was now a possibility. Mundane aspects of winter life in the province—snowshoeing, for example—became both sport and entertainment, and the season itself became something to be consumed.

The first winter carnival, held in 1883, had little to do with the modern carnaval de Québec. For one thing, it took place in Montreal. It was little-advertised; it did not reach much beyond the city’s English-speaking population, nor did it draw any great number of visitors from the surrounding regions, let alone from outside of the province. Nevertheless, this proved to be the essential foundation for future carnivals. The event returned the following year and drew the interest of French-heritage residents.

Tensions between the two cultural groups and between the eastern and western sections of the city soon imperiled the future of the event. Animosity burst into the open at the end of 1885; there was no carnival in 1886. It may have been just as well: the city had, in recent months, experienced a smallpox epidemic and received unfavorable press coverage that would have undermined a large-scale event. A meeting at the Richelieu Hotel in Montreal in October 1886 brought French and English business leaders back to the same table. Attendees all seemed interested in renewing the carnival tradition. Tellingly, many were hotelkeepers. Economics drove the return of the event and a higher interest facilitated interethnic cooperation.

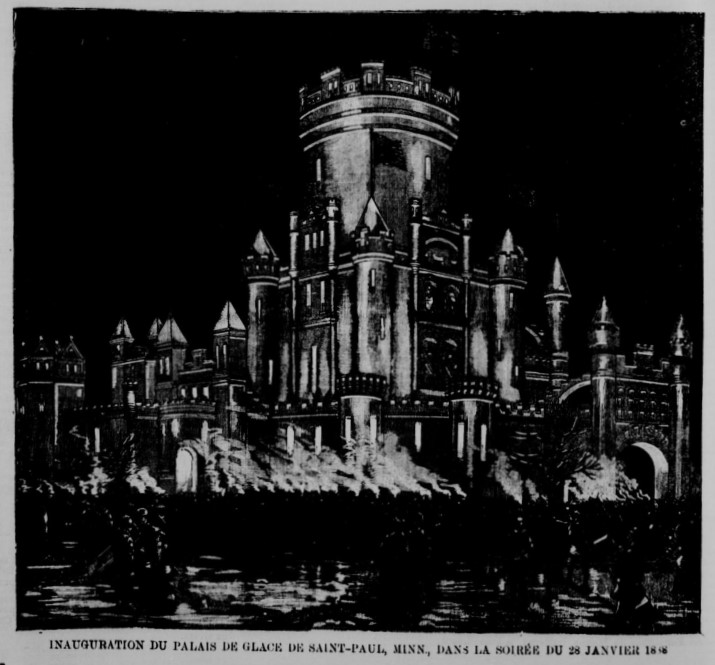

Other cities took note. In January 1886, newspapers reported that Halifax would soon hold a carnival. Both St. Paul, Minnesota, and Burlington, Vermont, held their own in February 1886, though Burlington’s was postponed by a week due to fickle weather. The next year, residents of Hamilton, Ontario, talked of having a similar event; in 1889, it was Ottawa’s turn.

This occurred despite reports that mispresented Canada and its climate. In 1883, Paris’s Le Nouveau Monde offered an account of the Montreal carnival that seemed to place it at the north pole—this was apparently a land of eternal snows. The cartoonish depiction, which a Quebec newspaper decried, misled Europeans; it might deter not only tourism but the immigration the country needed. Le Constitutionnel suggested that Canadian agricultural products be sent to international exhibitions abroad to show a more complete picture. This was again an issue in 1887, with an Italian paper now being the culprit.

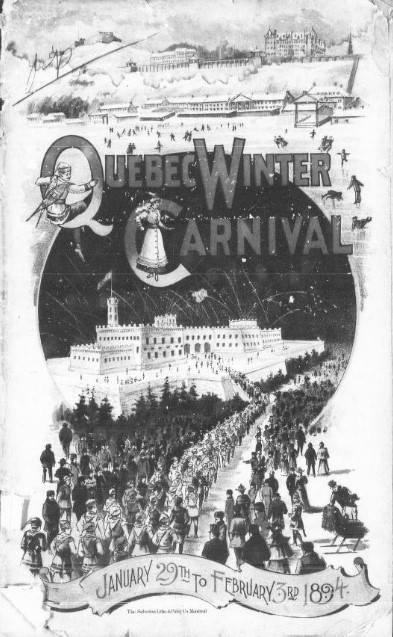

By 1893, Montreal’s carnival had disappeared. According to Burlington’s Free Press, the carnival craze might seem to have passed—were it not for Quebec City’s bid to hold its own in 1894. In doing so, the city revived winter carnivals in the province and helped establish a tradition—with interruptions—that continues to this day.

Not all were persuaded that this would serve Quebec City well. With predictable glumness, Jules-Paul Tardivel’s La Vérité disapproved:

A “carnival” is being planned in Quebec City for February. “Don’t talk to me of a winter carnival,” said the mayor of Montreal to a reporter from La Presse the other day; “nothing is more prejudicial to progress; a swarm of photographers falls upon our city and depicts Canada as a land of eternal snow and ice to other countries. Everyone is dressed in furs and Montreal seems to have the temperatures of Kamchatka.” The mayor of Montreal is exactly right: from a business standpoint, a winter carnival does infinitely more harm than good. It is only hotelkeepers who derive some kind of benefit, while the climatic reputation, if we may say so, of the entire province suffers greatly abroad. What’s more, from a different and more elevated perspective, the frivolity of a carnival could not be less recommendable. It is the English of Quebec City that have taken the initiative in this poorly thought-out bid.

Tardivel undoubtedly despaired that carnivals had, from the beginning, been secular affairs. He also happened to be wrong on several counts. The French and English of Quebec City enjoyed approximately an equal share of the positions on the various planning committees, with former premier Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière serving as the lead organizer. Sheer attendance would also refute Tardivel’s view of the event and its worth.

So, what did the first Quebec City carnival consist of? The panoply of athletic competitions featured sports that still have pride of place today: curling, hockey, skating, snowshoeing, skiing, and horse racing. With large crowds in attendance, winter hobbies and club activities became spectator sports. This is not counting people-watching: the wealthy and powerful visited Quebec City and drew interested gazes. Among them were Lord and Lady Aberdeen—the governor general and his accessible young wife—and John Jacob Astor.

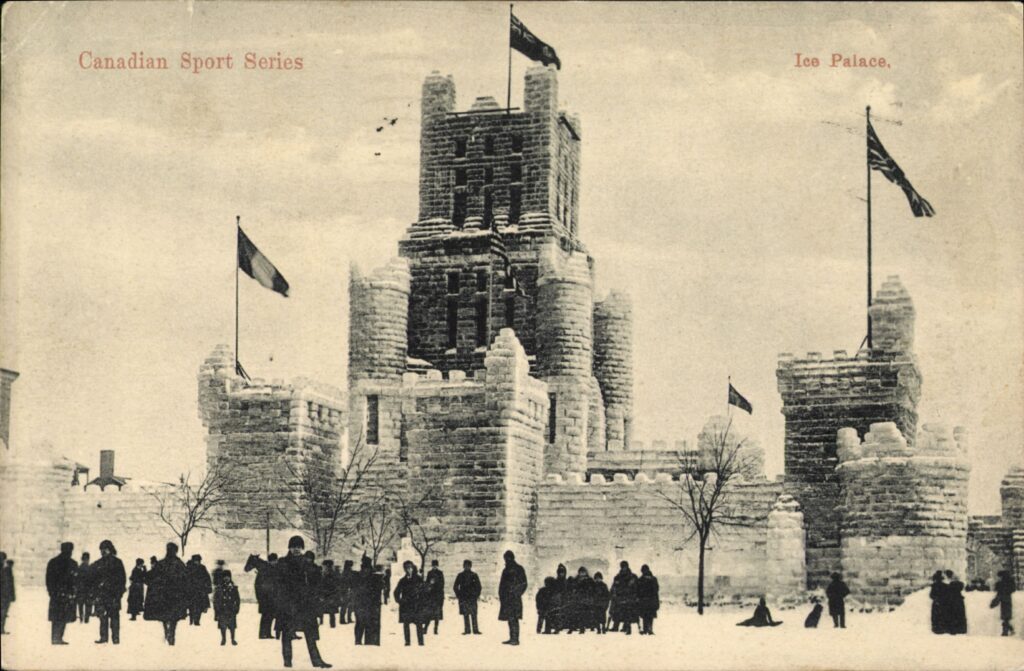

The opening day of the week-long celebration included the official inauguration of the ice castle and ice slides, music, and a fireworks show. The crowd that gathered again for fireworks later in the week led one journalist to make a favorable comparison to the bustle of the Chicago World’s Fair, which had closed only a few months earlier. On the second day, many residents and visitors joined in a costumed dance at the Grande Allée ice rink.

[I]t was with the satisfactory feeling of having thoroughly done its duty that the city and its visitors got ready to go to the skating rink this evening and be dazzled. And what with the decorations, the lights, the music, the dresses and the skaters themselves the scene presented was very beautiful. One of the members of the vice-regal party remarked that it was perfectly enchanting, and would have been worth coming a long distance to see, even if it had been the only attraction at the Carnival.

A reporter commented on the “Knights and Pawns, Pompadours and Highland lassies, queens, nurses, peasants, a fine specimen of the precious Dresden China,” and other costumed participants who took to the ice—and those in disguises that we would today find extremely offensive.

But, as far as attendees were concerned, the best was yet to come. On the fourth day, before an estimated crowd of 60,000, a snowshoed force of 2,000 reenacted the battle of Quebec of 1775, when Continental soldiers under Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold sought to wrest the city from the British. This “sham fight” over snow and ice ramparts on the Plains of Abraham was fought with Roman candles and blank shells—a dazzling event that would stand out in recollections of the carnival. The foregone conclusion of the battle added to the happy impressions: this was a moment of civic pride in which residents and their small garrison had successfully fended off invasion. A yet more important battle took place, however. Quebec City prevailed over Montreal in hockey.

Amusements also included a concert and a grand parade. “Canada may hold a thousand winter carnivals, but never will she show a spectacle to excel to-day’s parade,” reporter Julian Ralph noted, and detailed descriptions of the floats corroborate his assessment. Attendees could also view ice sculptures. Other carnival attractions were located outside of the city. The program for the 1894 carnival advertised visits to the “Indian” village in Lorette, the shrine at Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré; and a mock lumber camp closer to Quebec.

Quebec City had gone all out—outshining Montreal while offering a program that could not be sustained on an annual basis. The organizers had at least shown what could be done, bad press abroad (and Tardivel) be damned. Mass entertainment, boosterism, and a culture of consumption had met and provided new opportunities for economic development and a new appreciation for winter. The carnival in turn provided inspiration well beyond Montreal and Quebec City.

A Note on Sources

Sylvie Dufresne’s work on Quebec’s winter carnivals is an essential starting point; see, especially, “Le Carnaval d’hiver de Montréal, 1803-1889,” Revue d’histoire urbaine (1983) and “1883-1889: Quand Montréal avait son carnaval!” Cap-aux-Diamants (2001). BAnQ’s piece on the carnival tradition also features valuable sources. Foreign perceptions of Canada appeared in Le Constitutionnel, April 16, 1883, and Le Monde illustré, May 21, 1887; Tardivel’s take appeared on November 18, 1893. Among other pieces, I consulted the Burlington Free Press for the weeks of February 15 and February 22, 1886, and L’Electeur (based in Quebec City) through the duration of the 1894 carnival. The guide and souvenir of Montreal’s second carnival are available online, as are the program and a lengthy overview of the 1894 event in Quebec City. Readers may also enjoy Melody Desjardins’s “Cultural Costume Trends That You See at French-Canadian Winter Festivals” on Moderne Francos.

For more on the winter traditions of French Canada, check out the following posts:

How wonderful I went some 10 times in my life. I love winter in Quebec. I love Canadian. I grew up in a Rhode Island French Canadian enclave. Je me souviens