An earlier version of this essay appeared in the winter 2022-2023 issue of Le Forum, the quarterly publication of the Franco-American Centre (University of Maine). Please cite appropriately.

On both sides of my family, I am a direct descendant of individuals who elected to live and work in the United States. See, on the migrations of the Lacroix family, “A French-Canadian Journey,” Part I and Part II.

* * *

In Montreal, Dr. Daniel Tracey and Stanley Bagg were locked in a close and occasionally violent election contest. On May 21, clashes between Patriote and Tory supporters—a glimpse of the battles to come later in the decade—took a tragic turn when soldiers opened fire and killed civilians. At the end of the month, ships sailing from Dublin brought immigrants as well as cholera. The bacterium spread through Lower Canada and took thousands to an early grave. Among the victims was Dr. Tracey, who had triumphed at the polls. Meanwhile, in the countryside around Quebec, larvae hatched in wheat stalks and decimated the crop. They would return annually and cause near-famine conditions in the middle of the decade.[1]

To many in the St. Lawrence River valley, the year 1832 may have seemed an annus horribilis. No doubt it was for Guillaume Larocque of Chambly, aged 9, who lost his father in July. Guillaume père died at the age of 42, most likely a victim of the disease those insalubrious Irish ships had brought. In his time, the senior Guillaume Larocque had been an innkeeper. He left behind a wife, Marie Anne née Gélineau, and several young children—and he left them some means. The next year, the value of goods in the couple’s “matrimonial community” was just under £5,000, though nearly half of the amount lay in debts owed to them and they themselves owed £1,000.

According to their marriage contract, Marie Anne was to serve as tutor to their children. But, by the end of 1833, their uncle, David Larocque, had been appointed tutor and Marie Anne had renounced the community of goods she held with her late husband. As a result, £266 were set aside for each of her four minor children, including Guillaume fils, the eldest. The reason may lie in Marie Anne’s imminent wedding to François Lalanne. Their marriage contract made no mention of children from prior spouses—though the younger Guillaume attended the signing of the contract, assuredly with mixed feelings.[2]

Adrift and Across the Border

Little of Guillaume Larocque’s youth is known to us. He may have lived with his stepsiblings or with his many cousins in his uncle David’s household. Perhaps he benefitted from the support and protection of his godfather, the eccentric physician Jean François Bossu dit Lionais, who provided for Guillaume in one of his many wills. Lionais, a dedicated Patriote, spent the winter of 1837-1838 in prison. He died only a month after his liberation. His latest will left nothing, it seems, to his godson.[3]

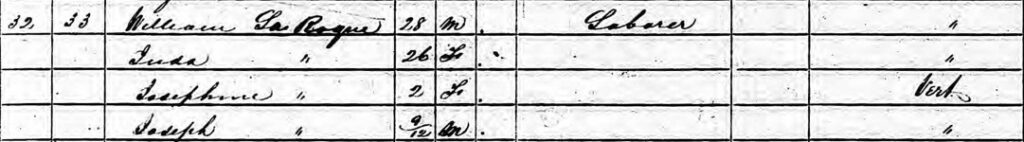

Thrust into an uncertain future by the death of his father, Guillaume then witnessed agricultural woes, rebellion, the economic turmoil of the 1840s, and increasing competition for land. It is therefore not so surprising to find him—like thousands of compatriots—in the United States in 1845 and, still, in 1850. In 1845, his stepfather, François Lalanne, pledged £1,743 to Larocque. The promise of such capital enabled him to marry; he would have the means to provide for a household. He wed Julie Hébert, of whom we know little.[4]

The couple lived in Addison, Vermont, 90 miles due south from Chambly, but by no means were they alone or isolated. In 1850, their next-door neighbors were the Canadian-born John and Elizabeth “Aber” who, by virtue of their ages, were almost certainly Julie’s parents. On the Larocque side, Guillaume’s uncle Albert also lived in Vermont. He lived in Bridport, just south of Addison, with his family; the nephew may have sought to follow his example. Several of Albert’s sons—Guillaume’s cousins—would reach places of influence in the Catholic Church, including Paul, who became the second bishop of Sherbrooke.

Addison, a predominantly agricultural community abutting Lake Champlain, was not an unusual destination for French-Canadian immigrants. Even at this time, people along Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River had a long history of cultural and economic exchange. Steamboats and other vessels plied both waterways and, only a few years later, railways would tighten cross-border ties. An enduring symbol of these ties was the Catholic pastor of Chambly, Pierre Marie Mignault, who had buried Larocque’s father in 1832. Mignault long served as a missionary to Canadian migrants south of the border.[5]

The transportation network combined with employment opportunities to pull young people like Larocque to Addison and surrounding towns, though many would return to Lower Canada. In 1850, more than 1,200 French Canadians lived in the nearby communities of Ferrisburgh, Vergennes, New Haven, Middlebury, and Shoreham. In some areas, these Canadians already represented 15 to 20 percent of the local population. Like many of the migrants, both Larocque and his presumed father-in-law—Jean Baptiste Hébert—appear in records as unspecified laborers. Hardly were they men of means and local influence. They lived on a cultural frontier, their tenuous social position made raw, no doubt, by overt expressions of condescension. Culture amplified the sense of a rigid class boundary between French Canadians and Yankees. Yet the work performed by migrants did not differ substantially from the labor they would have offered in Canada—had Canada provided the same paid opportunities. In short, culturally and economically, by no means was Larocque cut off from the world he knew in and around Chambly. This stay abroad was, in any event, meant to be temporary.[6]

The money promised by Lalanne in 1845 may have been slow to come. The two men again stood before a notary in Saint-Mathias in 1850. This latest contract, another financial obligation, listed the earlier sum, plus interest, and rights tied up in the succession of the long-dead Guillaume Larocque père. We have reason to believe that the younger Larocque, now aged 27, was eager to secure those sums. He and his wife were now parents to two young children.[7]

Home Again

A few days after Christmas, 1852, the Lalannes and the Larocques joined in a rite that was enacted thousands of times in the history of Lower Canada and Quebec, a rite that reflected both households’ life cycles. François Lalanne, aged 60, retired from active life. He and Guillaume’s mother donated their estate in Saint-Mathias to the younger couple, who in turn pledged to support them through their remaining years. That support involved an annual supply of twelve cords of wood, 300 lbs of salt pork to be delivered every December 24, the use of a horse and buggy, the promise to care for them and seek out a doctor when they became ill, and much, much more. Larocque agreed to donate £400 to each of his stepsiblings upon either their wedding or their reaching adulthood. Upon François and Marie Anne’s deaths, Larocque would also pay for twenty-five Low Masses to hasten their eternal repose. Until then, the Lalannes would occupy the south side of the house and the Larocques, the other half. Thus, on the eve of his thirtieth birthday, Guillaume was a cultivateur, a landowning farmer, settled again in the region of his birth, and no longer a common laborer left to seek his bread in foreign lands.[8]

An arrangement that was meant to be permanent proved otherwise: the Lalannes and the Larocques were living apart at the dawn of the 1860s. The latter occupied a one-story, single-family wood-framed house. Guillaume’s stepsiblings now had a hand in caring for the older couple. In 1871, widowed again, Marie Anne was living with a son from her second marriage. It may be that the shared house had become cramped, but Guillaume’s noticeable absence in the acts of Lalanne sacraments would suggest a fracture within the family.

In Saint-Mathias, the Larocques lived a conventional life by the standard of nineteenth-century French Canada. They worked to the rhythm of the seasons and rested by the rhythms of the Church. Julie bore twelve children in twenty-four years and all but one lived to adulthood. Before long, it was Guillaume and Julie’s turn to think of “placing” the next generation. Dowries for the girls were one thing; land that would enable the boys to support households of their own was another matter entirely. In March 1870, Guillaume traveled to Montreal and committed to the purchase of a 140-acre plot in the Township of Stukely, in the Eastern Townships. He paid $200 outright and, per the contract, agreed to disburse the remaining $2,300 over the course of five years. This was a dramatic step in the life of the family. Minus Guillaume’s time in Vermont, the Larocque line had lived in the Chambly area for a century and a half—almost ever since the first Guillaume had settled in New France. The Townships were rapidly filling up with French Canadians and it seemed the family would soon be joining the rush to these “new” lands.[9]

Industrial Proletariat

Five months after the Stukely deal, the Larocques were not haying, but sharing a dwelling with English and Scottish families in industrial Attleboro, Massachusetts, a town that neighbors Central Falls, Rhode Island. They had instead joined the rush of Canadians to Northeastern mill cities. According to one estimate, there were approximately 35,000 French Canadians in Massachusetts and 104,000 in New England in 1870. Those numbers more than doubled in the subsequent decade and this despite a long, hard recession that paralyzed industry in the middle of the 1870s. Like many compatriots, “William Rocks” became a common laborer again. In 1870, while Julie kept house, all children aged 8 to 21 were employed in a cotton mill. The whole family worked, as they had in Quebec—but that work was unlike anything they had seen north of the border.[10]

The move to Attleboro highlights the connection between rural fields of migration in New York, Vermont, and Maine and the cities of eastern New England. We don’t know whether Guillaume returned from Vermont with financial capital—but, from living in predominantly English-speaking, Protestant communities with different customs, he did acquire cultural capital that would serve him years later in Massachusetts. He spoke English, as his sons would. Having crossed the border once, his imagination and prospects could reach beyond Quebec. The dream of land owned free and clear in the Eastern Townships involved a second journey in the United States. In the process, the children’s horizons also broadened.

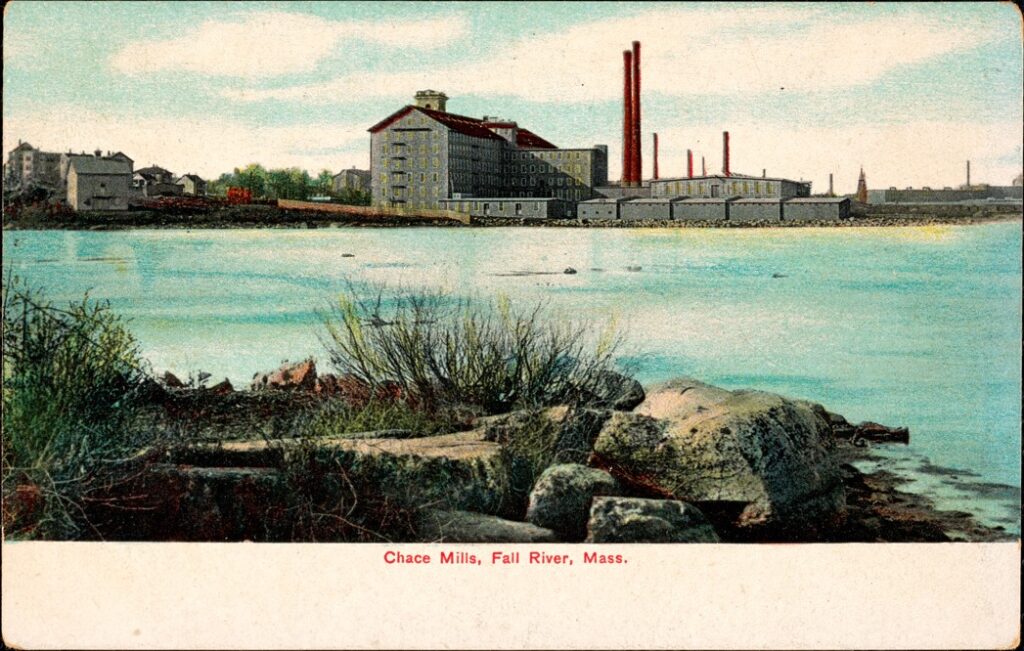

At some point, the dream fell through. The Larocques were still in Massachusetts in 1880, this time in Fall River. The new locale brought no great change in their circumstances. In fact, four of the children had now spent a decade in cotton mills. Only one had left the household. Three were over the age of 21—delayed family formation that generally implies rough financial straits. Their time in Chace Mill tenements on Baker Street says as much. In the early 1880s, a man hired by Chace refused to meet an essential condition of employment: operatives had to move into company tenements. The man objected to the unsuitable living conditions. He was promptly fired and fellow Chace workers walked out in solidarity.[11]

By no means was the life of the Larocque family confined to the large stone edifice overlooking the Quequechan River where they spent their working hours—60 hours a week, most likely. In Fall River, the family found a much larger French-Canadian population than they had in Attleboro. Their own tenement was home to the Dumas and Vincelet families; a few doors down lived another band of Larocques. The city had several French-Canadian national parishes and, at the turn of the 1880s, a rapidly growing network of cultural institutions, including the Ligue des Patriotes. Guillaume, Julie, and the children may well have heard Father Pierre Bédard’s sermons and the fiery addresses of a young attorney named Hugo Dubuque. They may have been living in Fall River when Honoré Beaugrand penned Jeanne la fileuse. Guillaume, had he read it, might have recognized the countryside that Beaugrand depicted and shared his frustration with Canadian political elites. Either way, the Larocques had community, if nothing else—and, financially, there may indeed have been little else.

Theirs was a dynamic urban environment that tantalized them with modern amenities lying just beyond the reach of the tenements. It was also a milieu rife with conflict. The Irish and French of Fall River typically stood on opposing sides of the picket line; they fought over Church institutions. At one time, a physical altercation even erupted in the pews. Each group sought to assert some control over their collective destinies in the United States while facing acute economic pressure that was neither’s doing. Guillaume Larocque, having heard the roar of rebellion nearly half a century earlier, now witnessed clashes of a different kind.[12]

Through the relentless stress of providing for his family, we can afford one safe assumption about Guillaume. He did not despair. Nor did he lose sight of la patrie. Like most migrant families, the Larocques assuredly visited the home country on multiple occasions while residing in Massachusetts. They may well have returned to Saint-Mathias during the summer or made some sort of attempt in Stukely. We do know they were on Quebec soil in 1882.

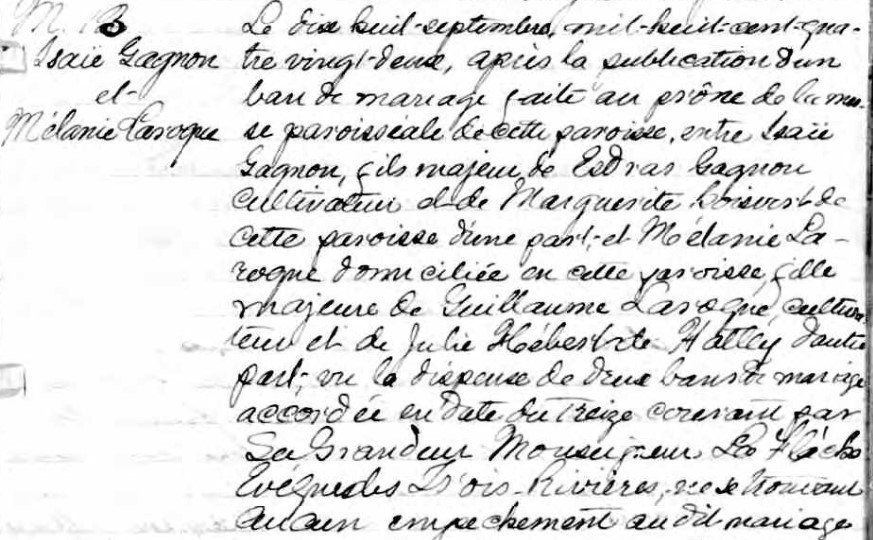

On the Land: Windsor

Slowly, Guillaume and Julie’s children began to leave the household, including daughters whose gendered horizons changed considerably through wage labor and their community of female mill hands. The French priest Adrien de Montaubricq, the founder of the first French-Canadian national parish in Fall River, celebrated Célanire Larocque’s marriage to Joseph Proulx in 1876. Through this couple, Isaïe Gagnon of L’Avenir met Célanire’s sister, Julie Mélanise. They married in Quebec in 1882. At that time, Guillaume, Julie, and the other children again were living in Hatley, just north of the border in the Eastern Townships, and Guillaume was again a cultivateur. The peripatetic journey was not yet at its close, however. The family returned to Fall River, now emerging as the largest center of French-Canadian population in the United States.[13]

The Larocques were still living in Massachusetts when, in 1887, Guillaume put down $900 on a plot of land in Windsor, twelve miles north of Sherbrooke, Quebec. The purchase announced the final chapter of the parents’ lives. By this time, Guillaume had spent half of his life, maybe more, on U.S. soil, no doubt as a means to an end. The whole household had scraped to return to Canada and to a life that had not lost all of its charms.[14]

Windsor was a small industrial center on the rail line between Sherbrooke and Richmond. It boasted a paper mill and a powder factory. It was one of many small regional centers that experienced industrial growth at the end of the nineteenth century—centers that would help retain workers in Quebec. But the Larocques had seen enough of industry. Aided by two adult sons, Guillaume farmed. The oldest of their children, Josephine, now nearly 40, helped Julie. Laura, the youngest, worked locally as a schoolteacher until she married James Kellett in 1897. Not that they were on a perfectly secure footing: the family continued to carry financial baggage. Guillaume borrowed $350 from powder manufacturer Robert Chapman in 1892. Putting up his 200-acre farm as a guarantee, he pledged to repay the amount in three years. The debt was not paid in full until 1899.[15]

By then, Julie had passed away. Guillaume lost a partner of fifty years who had weathered adversity by his side. The wills they had signed in 1894 said little of the state of their affairs. Each designated their two sons, Murat and Siméon, as their legatees and heirs, who would have an equal share in the parents’ estate. Guillaume signed another will in December 1900. It may have been a sign of declining health. He passed away at age 78 in November 1901.[16]

From One Generation to the Next

Guillaume and Julie Larocque witnessed most of the nineteenth century. They experienced the drama of their times: immigration, urbanization, industrialization, and the transition to a consumer economy. Their lives are evidence of the economic challenges faced by residents of Lower Canada (and later Quebec) and the means by which they provided for themselves and the next generation. The lives of their children are, in fact, evidence that families that returned to Quebec after an American sojourn were not entirely back where they started. Even after repatriation, there were lasting legacies to life and work in the cities of the Great Republic. The Larocques had seen a wider world—to which some would return.

We might think of Julie Mélanise, the third daughter, and her husband Isaïe Gagnon. They spent the latter half of the 1880s in Fall River—in Chace employ, according to one city directory—then came to live in Windsor. In 1909, they returned to the United States. This time they went to Lowell. Most of their own children settled definitively in Quebec. Their daughter Laura—renouncing work in an American mill—married Adélard Boisvert of L’Avenir in 1911. At least one, William Gagnon, remained in the United States. He lived and died in Nashua.[17]

Guillaume Larocque’s sons similarly left the province again, one of them earning passing fame. Agriculture enabled Guillaume to escape mill life; his second son, Siméon Henry, known as Sam, escaped thanks to the great American pastime.

Sam Larocque never reached the heights or the celebrity of a Nap Lajoie. But, in the niche world of early American baseball, the kid from Saint-Mathias became a legend. Contemporary newspapers noted his strength; his longevity in major and minor leagues as a player, a coach, and an umpire; and the record he held for most single-game errors. His career took off when the Detroit Wolverines bought (for $600, no less) his release from the Lynn, Massachusetts, club. He was one of the earliest French Canadians to play professionally. After a few seasons in the Midwest, Sam found a momentary home in the South. At the age of 45 he married the 20-year-old daughter of a Memphis hotelkeeper; he would be naturalized in Alabama a decade later. He ended his working life as a watchman at the Chrysler plant in Detroit.[18]

The informant at the time of his death, in 1933, was his own brother Murat. The latter appears to have sold his father’s plot, perhaps to settle debts following a 1903 lawsuit that became front-page news in the Townships. Around 1916, having worked as a machinist in Windsor Mills, Murat brought his young family to Ontario. Opportunities created by wartime industries—the Great War was then its third year—may have had a part in this. Murat purchased a house in Walkerville, Ontario, which the city of Windsor has since absorbed. Like his brother, Murat worked for Chrysler. Their sister Célanire—Mrs. Proulx—also went to Walkerville. Thus the Larocque clan, widely dispersed and much tested, reunited in an old hub of French-Canadian settlement, the Detroit River, now revivified by the automobile industry. By this time, like countless French-Canadian families, their kinship network stretched across several provinces and many American states.[19]

The life choices made by Guillaume and Julie Larocque reverberated across generations. Today, few of their Quebec descendants would suspect that the elderly couple that passed away peacefully in Windsor around the turn of the twentieth century—seemingly indistinguishable from their neighbors—had such a direct encounter with American manufacturing and American culture. If the memory of those times has evaporated, the legacies are still palpable. From the 1830s and 1840s, generations of French Canadians sought to steady themselves in the United States; often, those journeys are not instantly apparent in surviving records. The particular case of the Larocques must make us wonder how the thousands of migrant families that returned from abroad together altered the face of their home province and created new cycles of migration.

[1] “21 mai 1832: Emeute lors de l’élection partielle dans Montréal-Ouest” and “28 mai 1832: Début d’une importante épidémie de choléra au Bas-Canada,” Lignes du Temps du Québec, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, https://lignesdutemps.banq.qc.ca/; Quebec Mercury, September 1, 1832.

[2] Contracts, Paul Bertrand (Saint-Hyacinthe), November 16 and 17, 1833. The figures are not in pounds sterling but in livres ancien cours.

[3] Paul-Henri Hudon, “Un bien étrange docteur à Chambly…” Le Montérégien, June 7, 2020, https://journallemonteregien.com/un-bien-etrange-docteur-a-chambly/.

[4] Bertrand, September 22, 1845.

[5] Patrick Lacroix, “Le cas particulier de la famille Mignault: Prospection d’une histoire transnationale,” Quebec Studies (June 2018), 37-55.

[6] Ralph D. Vicero, “Immigration of French Canadians to New England, 1840-1900: A Geographical Analysis” (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1968), 155; Kevin Thornton, “A Cultural Frontier: Ethnicity and the Marketplace in Charlotte, Vermont, 1845-1860,” Cultural Change and the Market Revolution in America, 1789-1860, ed. Scott C. Martin (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005), 47-69.

[7] Bertrand, September 27, 1850.

[8] Bertrand, December 29, 1852.

[9] Contracts, Léonard-Ovide Hétu (Montreal), March 15, 1870; Bertrand, March 16, 1870.

[10] Yves Roby, The Franco-Americans of New England: Dreams and Realities (Quebec City: Septentrion, 2004),16.

[11] “Fall River, Lowell, and Lawrence,” in Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, Thirteenth Annual Report (Boston: Hank, Avery, and Co., 1882), 276.

[12] Lacroix, “A Church of Two Steeples: Catholicism, Labor, and Ethnicity in Industrial New England, 1869-90,” Catholic Historical Review (autumn 2016), 746-770; Philip T. Silvia, Jr., “The Spindle City: Labor, Politics, and Religion in Fall River, Massachusetts, 1870-1905” (Ph.D. diss., Fordham University, 1973), 421.

[13] Roby, Franco-Americans of New England, 24.

[14] Contract, Joseph-Théophile Lactance Archambault (Saint-François), June 20, 1887.

[15] C. M. Day, History of the Eastern Townships, Province of Quebec, Dominion of Canada – Civil and Descriptive (Montreal: Lovell, 1869), 433-440; Contracts, Joseph Alphonse Bégin (Saint-François), October 13, 1892 and July 8, 1899.

[16] Bégin, November 22, 1894 (two items) and December 6, 1900.

[17] L’Impartial, September 26, 1957.

[18] “Sam LaRocque,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/l/laroqsa01.shtml; Boston Globe, July 26, 1888; Vicksburg Evening Post, September 1, 1908; Le Canada, May 11, 1914; Green-Bay Press Gazette, May 19, 1914.

[19] Sherbrooke Examiner, June 15, 1903; Quebec Official Gazette, May 22, 1909; Sherbrooke Daily Record, January 22, 1932; Windsor Star, December 14, 1946.

Additional Sources

Beyond the sources cited above, this research rests on sacramental records from the parishes of Saint-Joseph in Chambly; Saint-Mathias; Saint-Pierre de Durham in L’Avenir; and Saint-Philippe in Windsor Mills, all accessed through the Drouin Collection. Guillaume Larocque and family members appear in U.S. census returns for 1850 (Addison and Bridport, Vt.), 1870 (Attleboro, Mass.), and 1880 (Fall River, Mass.) and the Canadian enumerations of 1861 (Saint-Mathias, Quebec) and 1891 and 1901 (Windsor, Quebec). Isaïe Gagnon’s household appears in the U.S. census return for 1910 (Lowell, Mass.). Further details on family members were retrieved on Ancestry.com databases: Alabama, U.S., Naturalization Records, 1888-1991; Fall River, Massachusetts, U.S., City Directories, 1889-1891; Massachusetts, U.S., Marriage Records, 1840-1915; Michigan, U.S., Death Records, 1867-1952; and Ontario, Canada, Deaths and Deaths Overseas, 1869-1948.

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Thought-provoking.

Reminds me that our everyday ordinary living becomes another generations’ wondering about how-did-they-do-that?

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - July 29, 2023 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte