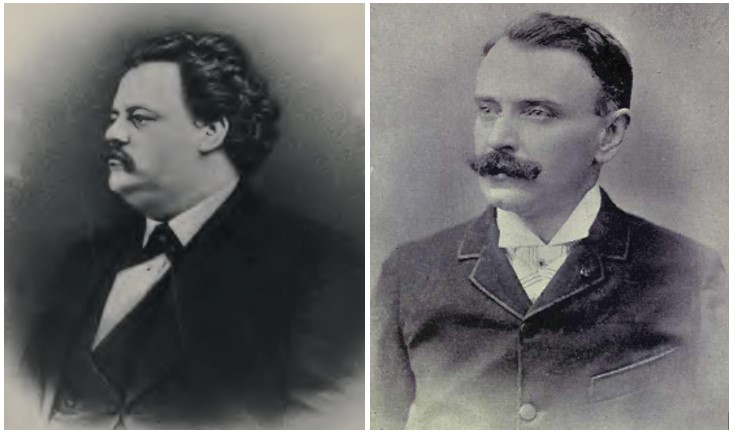

October 25, 1881: one of the best-known dates in the history of New England Franco-Americans. It was on that day that community leaders appeared before Carroll D. Wright, a Massachusetts civil servant whose latest report had represented French-Canadian migrants as “the Chinese of the Eastern States.” Ferdinand Gagnon, Hugo Dubuque, and other “influencers” answered Wright’s invitation and attested to French Canadians’ upstanding character and their increasingly sedentary ways.

Nearly all historians of Franco-America have closely studied this moment of collective affirmation—as with them, so with me. But hiding in plain sight in records of the time is a controversy that threatened to split community leaders’ ostensibly united front.

The timing was, in fact, impeccable. On the day prior to the hearings, Fall River’s Daily Evening News announced that Dr. Jean Baptiste Chagnon had initiated a slander suit against Fr. Pierre Jean Baptiste Bédard, the pastor of Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes parish in Fall River, who was expected to testify in Boston. According to Chagnon’s suit, Bédard had accused him of belonging to the Ancient Order of Foresters and—from the pulpit—forbidden parishioners from patronizing the physician’s practice and drug store. While the priest had not used Chagnon’s name, he had left no doubt as to his intended target.

The Foresters’ origins stretched at least to eighteenth-century England. On both sides of the Atlantic, the organization served as a mutual benefit and fraternal society. For figures like Bédard, the Foresters were suspect by virtue of their predominantly Anglo-Saxon, Protestant membership. Clergy were hostile to anything that resembled a secret society and Catholics were expected to join explicitly Catholic associations that were “accompanied” by chaplains. A distinct Catholic Order of Foresters came into being in the 1880s—after the dispute in Fall River. Ethnic frictions within this new organization led to the establishment of the Forestiers Franco-Américains in 1906 (they would be absorbed by the Association Canado-Américaine in the 1930s).

In October 1881, the Foresters were a foreign and dangerous institution to be ranked alongside the Masons. Father Bédard was acting as a societal goad, warning migrant French Canadians of the threats to their culture and their souls on U.S. soil. His attack on Chagnon aimed to maintain the boundaries of the nascent Franco-American community; it also threatened to bankrupt the physician.

Uncertainty weighed on Bédard as he traveled to Boston on October 25—not least because Chagnon demanded $25,000 in damages. An additional twist came in the person of Hugo Dubuque, who also went to Boston and whose legal services Chagnon retained; Dubuque, too, had to make a living. Despite the importance of conveying unity before the now-reviled civil servant, we can imagine what other tensions and unrecorded rivalries lurked between members of the Franco-American delegation.

Chagnon won his bid to embarrass Bédard (“a dictator in the political affairs of his congregation,” the suit alleged) ahead of his testimony. It is unclear whether he ultimately got satisfaction. In November, another Fall River newspaper stated that according to a settlement, “Father Bedard is to pay a subscription of $500 in aid of the new convent of St. Ann, to be built at the Globe [Village]; he is also to pay $100 costs of bringing suit, and is to appoint Dr. Chagnon physician to the convent at Flint [V]illage.” Chagnon quickly challenged the newspaper report as inexact, though without offering specifics. If the terms were close to the truth, Dubuque was compensated and the aggrieved physician won a sinecure.

Perhaps reflecting on the Bédard controversy, Dubuque later wrote that “from a moral standpoint, [Chagnon’s] character is beyond reproach. His independence of character is absolute and he has often earned himself adversaries and even enemies, particularly among his compatriots. His spirit is as foreign to injustice as his heart is to venality.” Was Bédard an enemy? Whatever the answer, in the small French-Canadian world of Fall River, the two men had to continue to coexist. When, only five months after the suit, a société Saint-Jean-Baptiste was organized in the city, Bédard and Chagnon became its first chaplain and physician respectively. This may have been an attempt to satisfy both and to keep the peace rather than a sign of wholehearted reconciliation.

The elasticity of community boundaries and personal relationships were again tested following Bédard’s premature death in 1884. The appointment of an Irish-American priest as pastor of Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes, unofficially a French-Canadian national parish, sparked a furor that far exceeded the Wright controversy in intensity. The Canadian population of Fall River’s Flint Village protested, disrupted, and boycotted church services. Ultimately, Bishop Thomas Hendricken took the extraordinary measure of placing the church under interdict, essentially locking out the parishioners and depriving them of the sacraments.

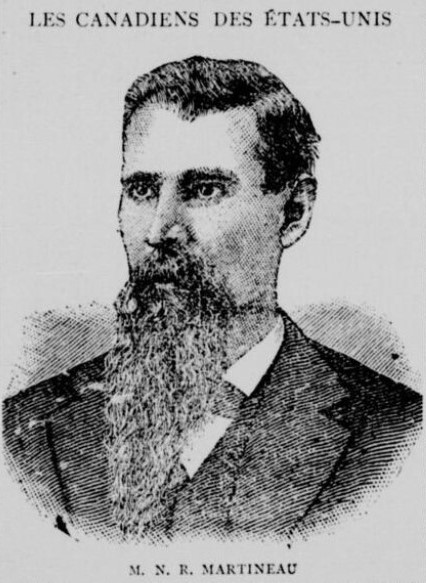

During the standoff, it was a relative unknown (in the larger arc of Franco-American history) who brought the parishioners’ cause to Rome. Narcisse Rodolphe Martineau, a native of Saint-Michel-de-Bellechasse and a former resident of Cohoes, pleaded on behalf of his compatriots. All the while, community leaders—namely Hugo Dubuque and Ferdinand Gagnon—pleaded with their compatriots to exercise patience and caution.

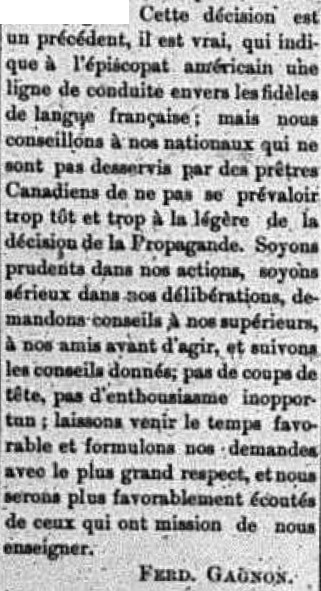

As Robert Rumilly has shown, Gagnon carved out extremely nuanced positions both on the Flint Affair and on the trial and hanging of Louis Riel. The apotheosis of Gagnon following his own premature death, in 1886, has tended to conceal the discordant notes offered by Le Travailleur, his paper, in this period. “The mission of the journalist,” Gagnon had stated in 1885, “is to mold [public] opinion, not to bear it.” He certainly lived up to that axiom. Not unlike Bédard and Chagnon, he quarreled with fellow journalist Honoré Beaugrand, whom he accused of being a freethinker and a Mason. Neither the Wright controversy nor the Flint Affair forged lasting unity. In fact, Gagnon could simultaneously buck popular sentiments and lament the lack of unity in the budding Franco-American press. His hometown newspaper, Le Courrier de St-Hyacinthe, asked whether he himself was perhaps not sowing the seeds of division.

Other personal clashes occurred in the midst of the church battles of 1885. The overheated atmosphere of French-Canadian Fall River continued to catalyze frictions—the product of bruised egos, a constant jockeying for influence, and a well-meaning desire to secure the integrity of French-Canadian culture. One clash involved Rémi Tremblay, whom Dubuque invited to join the local Franco-American newspaper as editor during the parish controversy. Tremblay’s opponent was Protestant professor Narcisse Cyr. While battling over the quality of education in Catholic and Protestant settings, they traded very personal barbs, Cyr even going so far as to call Tremblay a traitor. Tremblay responded in kind: he published a scathing epic poem about his counterpart that earned passing fame.[1]

If Catholic-Protestant clashes were to be expected, only a short time later Martineau contended with grumblings from the very parish he had represented abroad and at the episcopal palace in Boston. In October 1885, some parishioners expressed doubts about Martineau’s statements on his trip to Rome and the documents he claimed to have in hand. Local baker Joseph Amiot was not persuaded that Martineau had received documents from the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (la Propagande); he hinted at forgery. Martineau sued him for defamation of character to the tune of $10,000. He retained Dubuque as his legal counsel; the attorney and future Superior Court justice again got his cut. There might well have been a small cottage industry in these Franco suits and counter-suits.

Of course, these clashes were nothing new in Franco-American history; nor did they cease with the nineteenth century. Over time, politics played a growing part in personal dislikes—and personal dislikes played out in spite of politics. At the end of the 1880s, for instance, Dubuque depicted in a private missive a fellow Republican, Jean Misaël Authier of Cohoes, as “an empty head capable of compromising the best of causes.” The attorney, too, could have unkind words, it seems.

All of this can serve to remind us of the complicated history of survivance. Looking back on the mock trial of October 25, 1881, when xenophobia was put on the stand, or on the Flint Affair, or yet on other controversies all the way to the 1920s, we might be awed by the apparent single will and resolve of community leaders. That they were willing to band together despite intense personal frictions does speak to a higher commitment. On the other hand, Franco-American history was made by very human men and women who had to make their way and who hoped to imprint the community with their own values and vision. The dearth of biographies in the field of Franco history—where community elites and the working class both appear as homogeneous—may have blinded us to the personal element.

That personal element is not merely retrospective gossip or a distraction from the “real” issues. It provides insight into the challenges of community formation and helps us understand the daily experiences and preoccupations of historical characters that deserve to be more than generic stand-ins for survivance.

Sources

Details of Chagnon’s lawsuit appear in the Fall River Daily Evening News, October 24, 1881, the Boston Globe the following day; the Tennessean [Nashville], October 28, 1881; and the Fall River Daily Herald, November 9 and November 11, 1881. See, on Gagnon, Le Progrès de l’Est, July 3, 1885, and on the Martineau-Amiot affair, the Fall River Globe, October 19, 1885. Dubuque details the major figures and events of late-century Fall River in his Guide Canadien-Français [ou Almanach des Adresses] de Fall River, published in 1888. His view of Cyr and Authier appears in his correspondence with Major Edmond Mallet (collections of the Institut français, Assumption University).

[1] To complicate matters further, during the Frank Foster controversy, in 1883, Dubuque had seen in Cyr a secret weapon who might serve the French-Canadian cause by virtue of his connections to Boston’s upper crust.

Leave a Reply