See Part I here.

The development of Saint-Césaire, on the Yamaska River, announced the expansion of French-Canadian settlement into areas either previously unoccupied by white settlers or hegemonically English-speaking. It lay on the doorstep of the Eastern Townships, colonized successively by Loyalists, other Americans inching New England’s northern frontier onto Canadian soil, and British immigrants. The culturally foreign character of the region did not indefinitely deter French Canadians from its economic promises. By 1841, the growing French population in the Townships warranted regular Catholic missionary circuits.

The lure of these “new” lands can be seen with the Lacroix family, particularly Louise and her husband André Touchette, who settled down in Stukely Township in the 1850s. But Louise was preceded by her younger brother Edouard in the 1840s. In January 1844, a missionary priest celebrated Edouard’s wedding to Zoé Royer, whose parents had settled in Brome Township. Except for a few years spent in nearby Sutton, the couple would remain in Brome the remainder of their lives. (They died there in 1897 and 1907 respectively.)

Edouard’s in-laws had an unconventional history even at that early date. Zoé’s parents had spent several years in the United States (roughly 1829 to 1831); baptism records imply that she was American-born. By the time the Royer clan settled in the Townships, it had lived and labored in English-speaking settings. His wife’s cultural capital may have helped Edouard, whose parents lived in Saint-Césaire, acculturate to this “foreign” environment. We have every reason to believe that Edouard and Zoé’s children—twelve lived to adulthood—were functionally bilingual. They would have the tools to take advantage of new opportunities south of the border.[1]

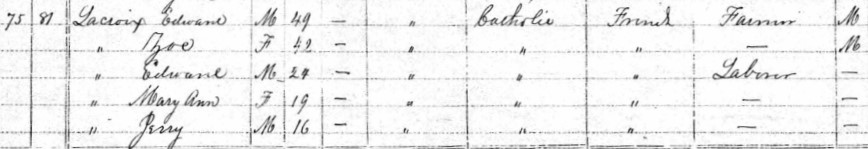

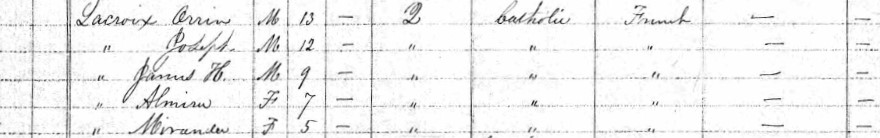

Edouard’s life cycle seemed to mirror his father’s, but with far fewer moves. In 1861, with as many as ten children to feed, Edouard was still a farm laborer. The family lived on a small plot that yielded potatoes and turnips; much of their income would have come from Edouard’s work on neighboring farms. A decade later, the family owned twenty-five acres. In the year leading up to the agricultural census of 1871, their plot had yielded 200 lbs of maple sugar and 17 cords of firewood. The women of the house had produced 150 lbs of butter and 22 yards of cloth or flannel. Theirs was a mid-sized farm with some animals, plenty of hay, a wagon, and probably a sled. That Edouard was forty-five years old with a full house by the time he reached the apex of his economic life cycle suggests, however, that life in the Eastern Townships could be as challenging as in the old settlements.

While there was ample development in the Townships in the 1860s and 1870s, the United States remained a powerful magnet. Here the Lacroix family exemplified continuity in outmigration from the pre-Civil War years to the end of the nineteenth century. Edouard and Zoé’s second son, known as Jerry, followed in his uncles’ footsteps and moved to Vermont as a young man. In 1875, the Catholic priest of St. Albans celebrated Jerry’s marriage to Franco-American Sophie Brosseau. This was only four months after the same clergyman had married Jerry’s cousin, a son of Joseph Lacroix and Domithilde Lavallée. Jerry and Sophie lived from farm work in northern Vermont.

Their story is as sad and tragic as any in this family. Sophie bore many children, and many died in infancy. It is unclear whether they ever owned a piece of land, considering the places we find them over the course of their adult lives. They were certainly in the St. Albans area for many years. It was there that Jerry was found to be contravening state law in 1892; he kept hogs despite orders of the State Cattle Commissioners, who had identified hog cholera and placed the farm under quarantine. By 1906-1907, the family was living on the town farm (often known as a poor farm) in Irasburg, in Orleans County; they had become charity cases.

As previously noted on this blog, Jerry followed a son to the factories of eastern Connecticut at the time of the First World War. The military census taken on the eve of the war reveals that he only had work experience in farming. He could ride a horse and handle a team, but had never worked with engines. He was then 5’7” and weighed 150 lbs.

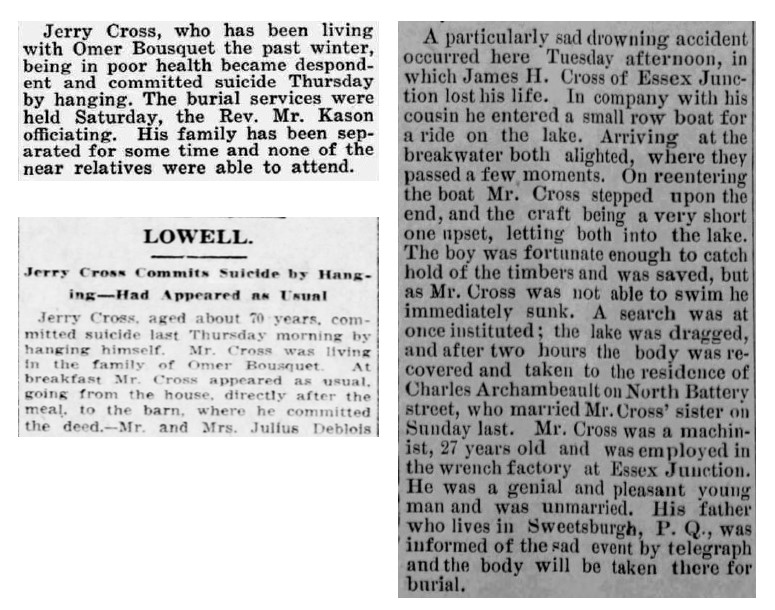

By the summer of 1918, Jerry was back in the Green Mountain State. Abandoned by his wife and children and now boarding in the Bousquet household of Lowell, Vermont, he committed suicide. He was 63.

Was Jerry the victim of a series of misfortunes? Was he less than hardworking? Perhaps he mismanaged his finances? Was he a drunk? Was he abusive? L’histoire ne le dit pas, as we say. Typically this is not the kind of story that is passed on. One generation whispers it and the next—ashamed or uninterested—forgets it.

The Lacroix family’s encounter with the United States did not end with Jerry. Even in his lifetime, he was joined by siblings. His older sister Mary Ann, then a widow, married Franco-American Charles Archambault in 1890 and they lived in Burlington for decades. After Charles’s death, Mary Ann would live with her son William and his wife Ina (Ernestine); she died in her eighties in Southampton, New York, in 1934. Another son of hers, Edward, was sued for divorce by his wife on grounds of cruelty and pecuniary neglect in the early twentieth century. He died of consumption a few years later.

James Lacroix, a sibling of Jerry and Mary Ann, drowned in Burlington harbor on June 24, 1890—a day after Mary Ann’s wedding. Perhaps he had taken the festive spirit a little too far. At the time he was working at a wrench factory in nearby Essex Junction; the report of his tragic end in the local press stated he was jovial and well-liked. Out at Gilman’s Corner, his parents, Edouard and Zoé, learned of the death by telegraph. This would be the fifth child they buried. They would bury two more, also young adults, in the 1890s.

Then we have Orin, also a son of Edouard and Zoé, who began working in Vermont in the early twentieth century. He was married, but neither his wife Clara nor their children appear to have traveled abroad with him. Clara was living with their daughter near Gilman’s Corner in 1911; in the census, a big, bold “D” marks her marital status. Were they in fact divorced? Clara’s visit to her estranged husband the following year suggests the fracture was not total and final.

In 1920, Orin was living with his sister Mary Ann in Burlington; three years later they traveled to the Townships together to attend their sister Angeline’s funeral. The cross-border connection remained. Orin died at the St. Albans Hospital in 1931, his final illness being a kidney disease. Several sons had by then followed him to the United States, one of whom worked for the Vermont Central.

James’s case and boilerplate obituaries notwithstanding, we seldom inherit historical records that state how loving, warm, hardworking, and decent our ancestors were. Virtue typically earns little press attention. So we should approach stories of apparent destitution, abandonment, abuse, and divorce with caution. They do not offer the full picture. On the other hand, we have to take them seriously and we have to wonder what led to unfortunate circumstances for so many members of the Lacroix clan in this era.

the Larocque-Lacroix household immigrated (LOC Lot 7479, v. 4, no. 2677 [P&P])

The temptation to romanticize one’s ancestors is always present in genealogical research. No doubt we all have brilliant, hardworking, dedicated people in our family trees. But many were dealt a rotten hand and we could not realistically want to trade places with them. Moreover, few people before our time had the emotional capital and mental tools to deal with tough social and economic circumstances. They experienced depression, anger, and regret. They lashed out or turned to drink. We achieve more and do justice to our ancestors by empathizing—not excusing their behavior, but explaining it—than by placing them on a pedestal. I suspect that would have meant more to them.

Okay, one last sibling. Edouard and Zoé’s youngest daughter, Mélanise, born in 1865, moved farther afield and helped substantiate the grande saignée as traditionally understood. She and her husband Pierre Alphonse Larocque, who was described as both a barber and a tinsmith, lived briefly in Vermont in the 1890s, where at least one child was born. They returned to Canada and, over a decade later, went to industrial Chicopee, Massachusetts, where they remained to the end of their lives. The lure of steady income from mill work was inescapable and could provide employment for the whole family. Their daughter Blanche was a machine hand in a knitting mill in 1920.

Mélanise and Pierre died in 1936 and 1944 respectively. It is particularly interesting that the last surviving of Edouard and Zoé’s children—Orin, Mary Ann, and Mélanise—all died on U.S. soil within five years of another. Whether they found all that they had hoped for or expected remains a mystery.

Another example from the next generation is in order. Orin Lacroix, a grandson of Edouard and Zoé and a nephew of his namesake, was born in Dunham, Quebec, in 1878. With his wife Marie Louise and their two children, this Orin left for Vermont in 1926. In the wake of the First World War, Vermont experienced a noticeable influx of French Canadians who, possibly flush with wartime earnings, acquired land south of the border. French culture was reinvigorated in many parts of the state. Though this was an era of intense xenophobia, some press outlets commented positively on the cash these migrants were bringing to the state and their efforts to improve old Yankee farms.

Family connections—and automobiles—may have aided in Orin and Marie Louise’s decision to move. Newspapers’ “social notes” hint as much; they also help humanize our ancestors by showing them in moments of leisure, when they delighted in one another’s company. In 1924, with several family members (including a sister-in-law, Mrs. Edson Lacroix), Orin and Marie Louise had “motored” to Ticonderoga, New York to visit relatives. On their return, their two adult children drove to Winooski and visited the agricultural fair in Essex. At the end of the year, Orin visited his namesake and his aunt Mary Ann in Beaver, near Fairfax.

Thus there was nothing foreign about Vermont when Orin, Marie Louise, and the “kids” settled there for good—as was very true for all other migrants in their extended family. Cross-border ties were sustained by Orin’s older brother Edson, who continued to motor down through the 1930s, and by Orin himself, who returned for the sad task of burying his siblings. We gain a portrait of the man through Second World War registration cards: at 5’10½” he was probably the tallest in the family but his 140 lbs were par for the Lacroix course. By then his hair had greyed; he had blue eyes and a ruddy complexion.

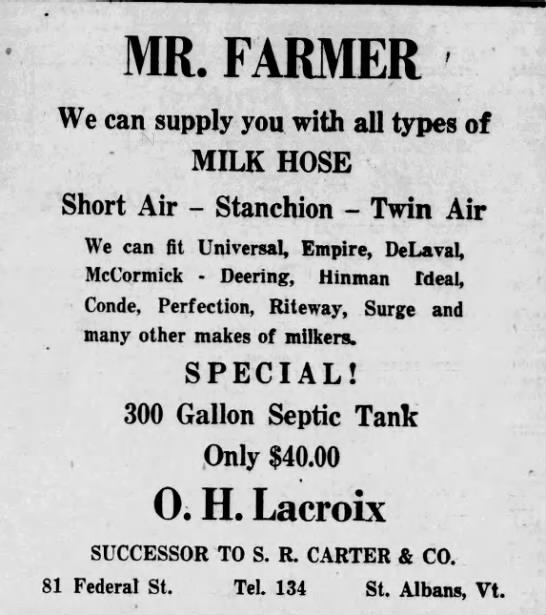

Orin worked in a dairy establishment in Franklin County and then sold farm equipment in St. Albans. He was a business owner, no small fact in light of the family history we have traced. For a time, his neighbors bore names like Cook and Sheehan. His son wedded the daughter of a hired hand named Archie Austin. They were married by an Episcopalian minister. When Marie Louise died and Orin remarried, the officiating party belonged to the Methodist Episcopal Church. The pattern of life was changing, but very gradually—and maybe more palpably as a result of automobiles, “party lines,” and record players than the move across the boundary.

The second Orin Lacroix died in St. Albans, Vermont in 1963, four days after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination and two days before Thanksgiving. Such now were the family’s reference points. He had been French-Canadian and American, but this kind of Franco-American story has received little study and scrutiny.

The Lacroix family’s path from Bellechasse down to the Richelieu and Yamaska basins, into the Eastern Townships and into the United States, was not particularly unusual. Family members who moved and went abroad starting in the 1840s were like thousands of other French Canadians who made the same journey in the same years. Theirs is a story of economic struggle and cultural metamorphosis; they represent an important slice of Quebec history—American history, too. However focused they were on their own survival and well-being, they were agents of a transformation that brought two countries in greater communication at the grassroots level. In this, they remind us that French-Canadian history is transnational and perhaps far less monolithic than we have come to think.

[1] Just as migrant French Canadians paid little heed to the political boundary, early Catholic missions served the faithful without regard for their place of residence. The parish of Stanbridge, one of the first in the Eastern Townships, some twelve kilometers from Lake Champlain (Missisquoi Bay), welcomed French Canadians from “across the line.” Families that appear in Stanbridge church records hailed from nearly all points in Franklin County, Vermont, as well as neighboring Canadian communities. On one October day in 1846, the many children christened by the pastor all belonged to American residents, suggesting that Father Leclair may have taken it upon himself to cross the border—a line that mattered little in the economic lives of thousands. Astride, a borderland increasingly marked by French-Canadian culture was developing.

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - August 7, 2021 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

Thanks for sharing. I’m trying to trace relatives for their path PRIOR to Saint-Césaire (Edouard Foisy). They too went from Saint-Césaire to Connecticut.

Interesting and important provocation for consideration, this “what is the family story really?” Might that make an interesting theme for one of your Acadian Archives series?

Just off the cuff thoughts

— our true stories aren’t only those that tell about the worst days of our lives

— the silences and secrets of ancestors have legacies in descendants

— so many stories need to be written down. I saw a wonderful quote the other day — to paraphrase — It’s said that history is written by the victors, but I think history is written by those who write things down

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, Ann! All good points! The quotation reminds me of Winston Churchill’s words, often misquoted as “History will be kind to me. For I intend to write it.” But perhaps the real act of kindness is passing on a written record to future generations.

As for the lecture series, I am definitely interested in integrating more family stories!