It is thought doubtful if any city in the United States has ever entertained as picturesque a gathering of wintersportsmen from across the Canadian border as it was Lewiston’s privilege to entertain during the past week-end. In any event Lewiston has eclipsed its neighboring New England cities in this respect, and for 36 hours, at least, found itself holding the center of the stage in the New England wintersport world.

– Lewiston Daily Sun, February 9, 1925

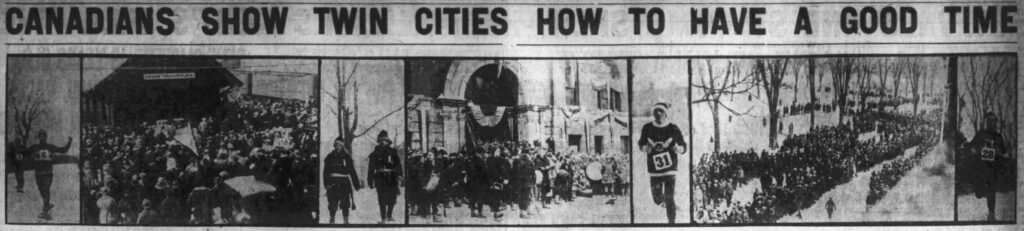

While hundreds stepped down from coaches at the Grand Trunk station, it likely seemed as though the whole world was gathering in Lewiston. The press had dispatched photographers. Cameramen had also come; images of the events would appear in weekly news features in theaters. This was Lewiston’s time to shine—and, as the epigraph suggests, it did not disappoint.

The occasion was the international convention of the Canadian Snowshoers Union held on February 7 and 8, 1925, though excitement had run high all through the prior week. Locals had cast thousands of ballots in a tight, five-way race for the title of carnival queen. Melida McGraw edged out Yvonne Leclair. The advanced guard of Montreal’s delegation arrived several days later in the form of two ordinary laborers—one of them a railway worker. Their arrival was notable for the physical feat they had just accomplished.

Adélard Turcotte and Wilfrid Dupré, both in their early thirties and both members of Montreal’s Molière Club, had snowshoed from their home city all the way to Lewiston. Their journey had taken them through Saint-Jean and Sweetsburg in Quebec; Newport, Vermont; Groveton and Berlin, New Hampshire; and South Paris, Maine. At some point, three men from Sherbrooke had joined them. Turcotte and Dupré both had experience with long-distance treks, but this eleven-day journey was something else. Their feet were continually wet and their hands became numb. They had started from Montreal with backpacks weighing 55 pounds. The backpacks had gotten gradually lighter and so had the snowshoers. Turcotte had lost 16 pounds by the time he and his partners walked into Lewiston on February 5.

The following night, local snowshoe club Le Montagnard kicked off the festivities. A spirited basketball game between Lewiston High School and Edward Little and a dance at the Armory provided entertainment to locals. By this point, organizers had decorated the city with American flags and the French tricolor. The absence of British flags was attributed to an administrative error—though in retrospect one easily suspects that this was an “intentional accident.”

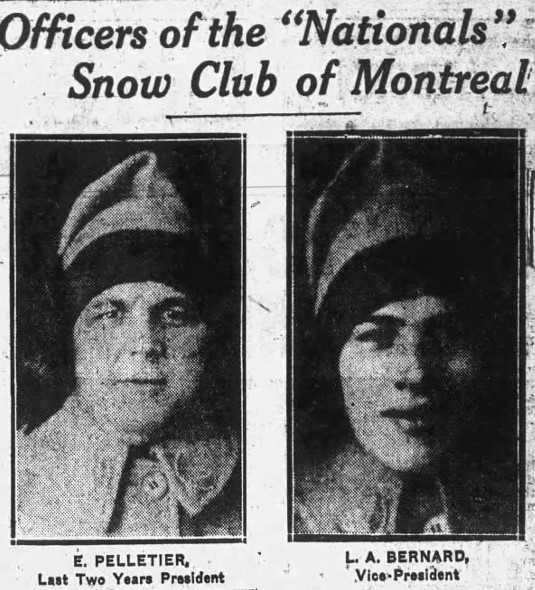

In any event, the city was primed for the convention by Saturday morning when, to a great cheer, the Montreal train appeared on the far side of the Androscoggin. Numerous towns and cities were represented among the travelers. Montreal, Quebec City, Sherbrooke, and Trois-Rivières contributed multiple snowshoe clubs to the event. Sainte-Thérèse, Saint-Jean, Saint-Hyacinthe, Valleyfield, Joliette, Drummondville, Thetford Mines, and Ottawa each sent one club.

In their bright and colorful uniforms, the groups disembarked and quickly formed into marching order. Before excited crowds, to the sound of trumpets and drums, they paraded up Lincoln, Cedar, Lisbon, and Pine streets to City Hall. There, toastmaster F. X. Belleau introduced Mayor Louis Brann. Brann richly praised the women of Canada, though, he also stated, local women were holding their own through Miss McGraw (“Lewiston has the most beautiful type of womanhood in the world”). He also gave credit where credit was due.

The mayor stated that the Franco-Americans are the backbone of Lewiston. The splendid growth of this city during the last 15 years has come, he said, thru the energy and foresight of the Franco-American. If Lewiston today is the splendid industrial center that it is, it owns [sic] it to the Franco-Americans . . . The mayor closed by saying “in a spirit of friendship and hospitality which has existed over 100 years between the people of our country along the border from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific while men of the same blood in other countries, were warring, I bid you welcome.”

Bands then played the Star-Spangled Banner and the Canadian national anthem.

Enthusiasm reached well beyond people of French-Canadian descent. According to the Evening Journal, Governor Ralph O. Brewster, who has gained rather dark notoriety in Franco-American history, “had the time of his life” at the event. Brewster traveled from Augusta by trolley, arriving at Lewiston City Hall only moments before the snowshoers. He watched as clubs played music and sang Canadian songs. In his speech, he discussed the close ties between the two countries and celebrated this gathering built on a footing of Christian brotherhood. “I am delighted to have been able to come here for this time,” he told a reporter. “I feel that it is one of those things which cement the friendship of two peoples more firmly than can be done in any other way . . . it will also prove of much worth in showing the world the possibilities of Maine as a winter sport resort.” The event may have been a political obligation, but it obviously promised greater opportunity from the standpoint of business and tourism. Brewster hoped Maine would return the favor and organize a friendly invasion of Quebec.

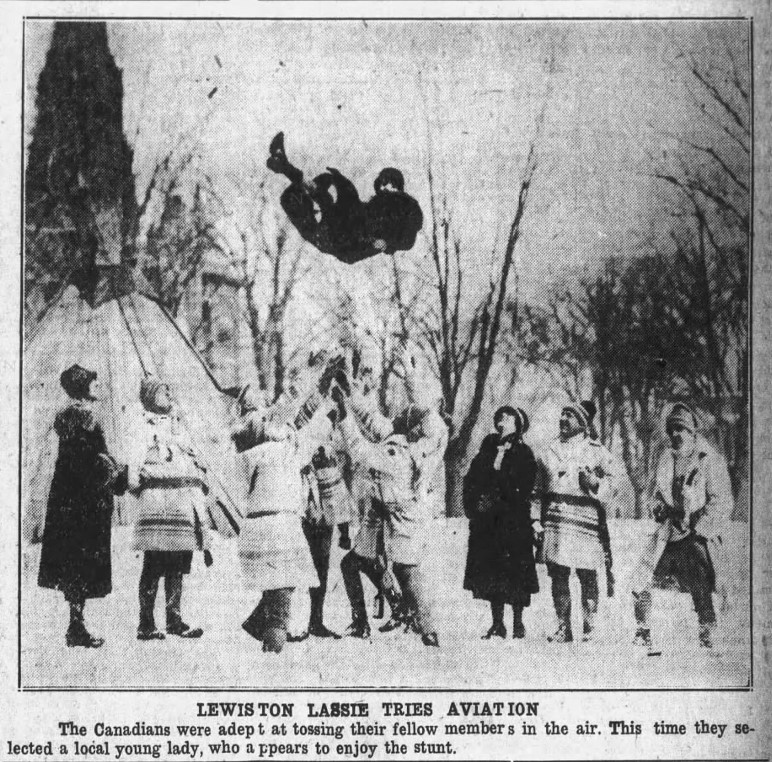

The afternoon was devoted to fun and games, including snowshoe and ski races at the park, where an ice palace had risen from the snow. Canadian clubs swept the races. Residents had a chance to see the mile-race record holder in action. This was 43-year-old Eugène Clouette, a father of fourteen children from Montreal. All the while, Quebeckers and Franco-Americans, men and women, mingled and celebrated. Newspapers commented on the amount of kissing between strangers. The revelry continued well into the evening. The day ended with a mock bombardment of the ice palace with fireworks, a hockey game, and a “smoke talk and convention business” at City Hall.

Predictably, the Sunday program included a special mass at the basilica, which followed another downtown procession. In early afternoon came the closing banquet at the DeWitt Hotel. Local and Canadian dignitaries shared the roster of remarks (the president of Montreal’s chamber of commerce and city councilors had made the rail excursion with the clubs). Mayor Brann thanked the indefatigable Louis Philippe Gagné of Le Messager for laying the groundwork for this event.

Brann was not the convention’s only thirsty attendee. According to the Daily Sun, “The occasion brought to Lewiston a revival of the pre-Volstead days.” A reference to “the wetness absorbed” indicates that the statement was not metaphorical. The country was now five years into Prohibition, yet it seemed to matter little as participants flashed bottles and flasks on the streets of Lewiston. Likely most of the alcohol had come with the Canadian clubs. Likely Prohibition officers and local police had been invited to look the other way to avoid incidents. It is little wonder that the mood across the city could only be described as elation.

Prohibition agents, let it be noted, were much more diligent on other occasions. A year later, Lewiston snowshoers visited their brethren in Montreal. On their return, agents boarded the train and found four bottles of liquor. It is less than clear whether the Lewiston men were responsible for the illicit cargo, but the officers noted that the train was “cleaner” than others they had inspected on similar occasions.

Hopes of reciprocal exchange were met by 1928. At that time, more than 350 people belonging to Lewiston’s eleven snowshoe clubs marched to the Grand Trunk station. With Mayor Robert Wiseman leading the delegation and special train coaches to accommodate the small army, they traveled to Montreal for the Canadian Snowshoers Union’s latest convention. Biddeford, Brunswick, Chisholm, Rumford, as well as Manchester, New Hampshire, were also expected to send snowshoers.

Then, in 1929, snowshoeing again made headlines far beyond Maine. Ol’ Eugène Clouette, the star of the Lewiston convention, was the class of the field in a Montreal-to-Lewiston snowshoe race. Of the seventeen men who left Montreal, only seven completed the journey. Wilfrid Dupré, who had made the trek four years earlier, finished third. Manchester men named Beaulac and Boulay also finished. But Clouette stole the show. He covered 297 miles in little more than 53 hours—at the age of 47. A hero’s welcome awaited him back in Montreal.

In Maine and beyond the interwar period featured unequaled athletic achievements, the celebration of winter leisure, increased tourism, efforts to nourish historic ties between Quebec and Franco-Americans, strange political bedfellows, and, of course, occasional “wetness.” Snowshoeing, now too often forgotten, served as a catalyst in each of these areas—and for a week in 1925, Lewiston was its international capital.

Sources

This story is drawn from Lewiston’s Evening Journal, issues of February 3, 6, 7, and 9, 1925; the Daily Sun, February 9; Augusta’s Daily Kennebec Journal, February 9, 1926; Portland’s Press Herald, February 4, 1928; and Montreal’s Le Devoir, February 2, 1929. The story of the 1929 snowshoe race was carried widely across the United States. Additional context is available on Meander Maine. A view of the ice palace appears on the Maine Memory Network; club uniforms are visible on this photograph from the Acadian Archives.

For more on winter and holiday traditions in French Canada:

Pingback: Lewiston: Winter Wonderland – NiCHE