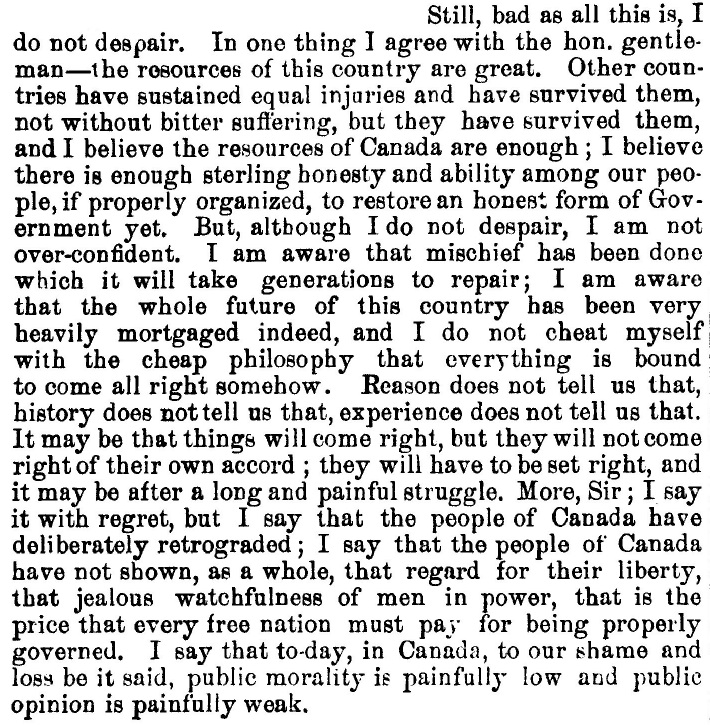

So declared Sir Richard Cartwright in the House of Commons in Ottawa exactly 140 years ago, February 29, 1884, while offering a vigorous response to the government’s proposed budget. Not that he knew any other kind of response: in the 1870s, Cartwright had emerged as one of the most outspoken and effective critics of John A. Macdonald’s Conservative Party. With his attention to figures and gift for rhetorical flourishes, he was a formidable debater in and out of the House of Commons. His reputation grew steadily through his political career—four years in the pre-Confederation legislative assembly, thirty-five in the House of Commons, and nearly a decade in the Senate. By the early twentieth century, he was an institution as much as Parliament.

Initially a supporter of Macdonald, Cartwright turned to the Liberal Party in the 1870s. With the zeal of a new convert, he confronted his former friends’ every political vice. He served in the administration of Alexander Mackenzie (1873-1878) as minister of Finance before returning to his attack dog role on Opposition benches.

This is old-school political history. At one time, the study of the past was chiefly confined to the lives and legacies of men like Cartwright. That this type of history has become less fashionable is for the better: historians have broadened their horizons in ways that have benefitted the field as a whole. Still, there may be one or two lessons to be drawn from Cartwright’s time in Ottawa and specifically from the debate that unfolded 140 years ago. It tells us something of patriotism, partisanship, and, as might be expected of this blog, depopulation.

In Cartwright’s view, it was all self-evident. There was something wrong with Canada, proof lay in the exodus, and the country’s Conservative government was to blame.

By 1884, the Macdonald government’s vision for Canada was well established. It is the vision that most Canadian readers of this blog learned in school. Macdonald had committed to replicating a feat achieved by the United States in 1869: the completion of a transcontinental railway. The famous last spike would be driven the following year. In 1879, the government had implemented high tariffs on industrial imports, which would help fund the railway and spur home-grown industrial production. The Conservatives sought to develop the North-West (the present Prairie provinces) and to that end fostered immigration from Europe.

All of this has been consecrated as a cornerstone of Canadian mythology. Macdonald’s National Policy secured for Canada an existence distinct from the United States’. Well, that is the work of hindsight. There were vociferous critics, Cartwright included, and no certainty that the Conservatives’ big bold plan would pay off, especially as Canadians continued to vote with their feet. We might in fact wonder how different the country’s political landscape might have been had the United States not served as an escape valve for the economically precarious for decades.

In Ottawa, the Opposition did its job. It denounced centralization, corporate handouts to railway interests, cronyism, ballooning government expenditures, the cost of tariffs passed on to consumers, etc. Soon, the North-West Resistance and Nova Scotia’s Repeal Resolutions would stand as glaring indictments of federal policy.

Cartwright was very much a man of his time in declaring that a Canadian settler was worth ten immigrants; he did not seem more empathetic to the plight of Indigenous peoples in the North-West than his adversaries. He was hardly a luminary when it came to the dispossession of Native lands through the influx of Canadian settlers, be they French or English. A pedestal honoring Cartwright would come with a cloud of floating asterisks.

We nevertheless find in his public and private remarks feelings that still echo to this day. There were many faults to be found and decried in the Conservative government. To raise inconvenient questions was expected. It came with the position and it was arguably an act of patriotism. Political vigilance is all the more important in a first-past-the-post system where there are few checks on the elected majority. In the 1880s, like today, this was fertile ground for hyperpartisanship. But beneath the parliamentary joust was something sincere. Cartwright was genuinely troubled by Canada’s inability to retain its people. He also had to contend with dejection from successive defeats at the hands of the Conservatives. (Little did he know, he would spend another twelve years on the Opposition benches.) In his response to the budget, he concluded:

Though claiming otherwise, Cartwright was certainly flirting with the despair that many politically attuned people have since felt, and still feel, whatever their political stripes. It may have been enhanced by his own uncertainty as to the medicine that would cure Canada’s ills. The nation was short on solutions.

That came out twice, in little political tempests, in the months following this debate. He first complained publicly that while Quebec sent its best men to Ottawa, Ontario did not, such that its interests were neglected. Predictably, some Conservative outlets in la belle province interpreted this as Quebec bashing. Then came more telling remarks.

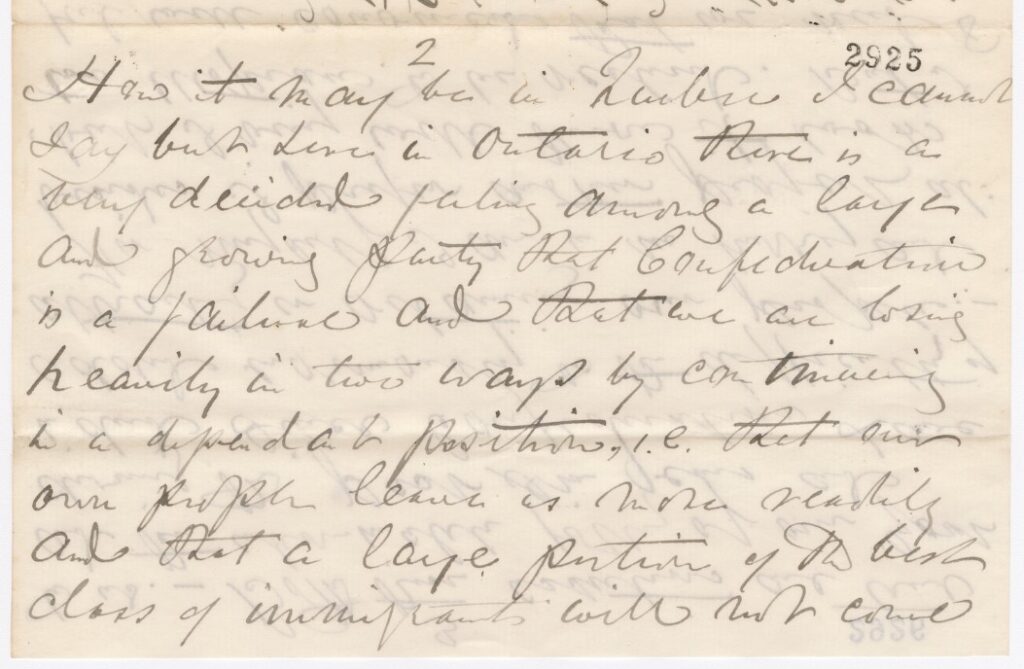

Various political paths lay open to Canada, declared Cartwright, from the status quo to an imperial federation to annexation to the United States. He floated an idea that seemed dangerously close to annexation: independence. While Macdonald worked to keep Canada out of the eagle’s talons, Cartwright hinted at increased autonomy from Britain. This was not a novel proposition, but it was politically risky. In fact, during the summer, perhaps in response to concerns raised by the man himself, he felt compelled to explain his statement to Henri-Gustave Joly, until recently the leader of Quebec’s Liberal Party.

In private, Cartwright again mentioned the loss of immigrants and the departure of native-born Canadians, suggesting that his claims on these issues were not merely political theater. Canadian independence, he conceded, might in time lead to annexation. But that was equally true of failed Conservative policies. Anything was better than the status quo, especially with the rate at which Canadians of all origins were migrating to the United States. Cartwright had no grand illusions about the mixing of English and French Canadians, but he believed in smoothing over what hostility existed in Parliament for the sake of the country.

On the strength of four consecutive electoral victories, Macdonald’s party won the battle of history, as though the “Old Chieftain” had himself written the textbooks. But remarks made in the course of an otherwise forgettable debate, 140 years ago, invite a better sense of contingency and the battles that were momentarily won and momentarily lost.

For one thing, the desperation that Cartwright felt in his political wilderness may have been matched only by the despair of ordinary people who surrendered to the inevitable. They followed work where it happened to be: south of the border. They still had a voice in Parliament, but it was in the nature of nineteenth-century policy tools to move economic conditions but slowly.

Meanwhile, in those very halls of power, despite the posturing, there were doubts on all sides. The Conservatives couldn’t be certain that the National Policy would yield its much-touted benefits. Cartwright didn’t know what it would take to reverse the flow of people. There may have been virtue in making that admission publicly, and there may be something to take away in our own day. Learning, perhaps, from Cartwright’s conflicted mind, we can find virtue in tempering our own acts of patriotism—speaking out against detrimental policies—with candid modesty about the challenges that stand before us collectively.

For more on these topics:

Leave a Reply