In the literary ferment of the late nineteenth century, Quebec authors sought to craft a new national identity that could be read back in time. Quite consciously, such authors as Louis Fréchette and Honoré Beaugrand jotted down and published old oral traditions that were at risk of being forever lost. (It seems they may also have invented stories that could pass as old folk tales.) The most famous of these may be The Legend of the Flying Canoe, ably described and commented by Ma famille canadienne-française. The Devil at the Dance, or The Handsome Dancer, is another well-known story. Frequent readers of this blog may also recall The Miser’s Ghost, as told by Beaugrand.

Charles Edmond Rouleau, whom we’ve previously met here, did his part at the turn of the century. Rouleau was involved in the spiritual politics of the day and wrote about the plague of emigration; he also contributed his own set of folk tales. His illustrated Légendes canadiennes appeared in 1901. (See Jean-Louis Lessard’s blog for an overview.) The following tale, taken from that collection and translated and reinterpreted in English, is a classic example of Quebec folklore, with themes and patterns that will be familiar to those who know of The Legend of the Flying Canoe and similar works. The images are all reproduced from Légendes canadiennes.

* * *

On the road from Baie Saint-Paul to La Malbaie lies a bridge that deserves almost no notice, short and unremarkable as it is. Locals know it well, however, for it has ever been guarded by a black cat, which serves as its trustee. It is so sturdy, so well-built, that not once in generations has it required repair of any kind. But such can be the works of the devil, as this one is. Yes! I tell you, be on your guard when you see the cat, for that bridge was built by Satan and none other, and he continues to claim it as his own.

How did it come to be? Many years ago, the stream that today flows under could be forded well enough in the dry summer months. But wagons and carriages stood no chance during the spring thaw; they were sure to be carried downstream and washed into St. Lawrence. Northerly communities might have to go on without outside help when food was at its scarcest.

In time, our friends in Quebec City secured a small sum and commissioned a local mason named Tremblay to build the bridge. Diligently, Tremblay set to work in late August, that year, but soon fell into the utmost despair—he was impeded by violent storms and struggled to find horses and workers. Fall was quickly lapping at his work and he began to fear he wouldn’t be done by winter. The bare foundations he had laid would be gone by the following summer. He would be discredited in the eyes of the public. In time, he was ready to give anything to see this damn bridge, ce maudit pont, rise before him.

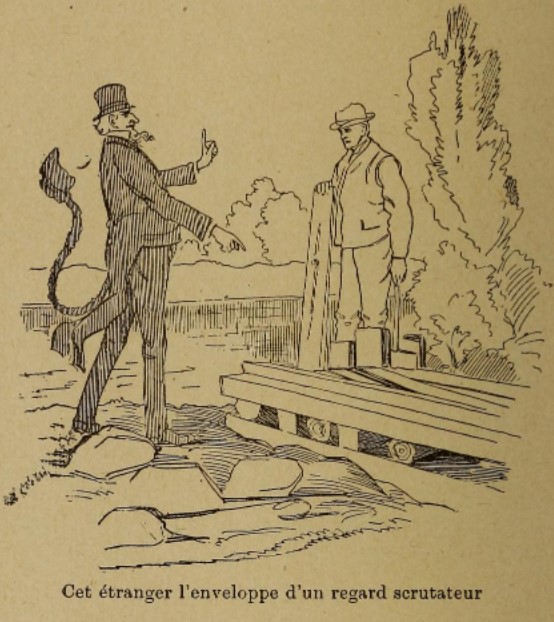

Tremblay had chatted up travelers all through his work, day after day; nearly all he knew personally, and a good many were cousins from neighboring parishes. But he didn’t quite know what to make of the lanky, immaculately-dressed stranger whom Tremblay found watching over him, after squaring another stone, in late September. He might have taken him for one of those Zaméricains if the man hadn’t spoken in a fluid French whose eloquence rivaled the local curé’s. Tremblay showed the courtesies that are only ever extended to strangers and promptly shared his discouragement.

The traveler listened, and smiled. “I myself am a contractor of a kind, and I may be of help. I can bring my men and they will complete the bridge in no time.” Our mason protested that government funds were running out, and he couldn’t afford to pay this stranger out of his own pocket. “Never mind that,” the latter replied. “I will build it and you can claim the work as your own. My terms are clear. You will be in my service until the debt is paid off.” Tired and willing to trust someone who spoke and presented himself with such authority, Tremblay accepted. “The bridge will be completed in a fortnight,” said the stranger. “And on the last day I will come for you.”

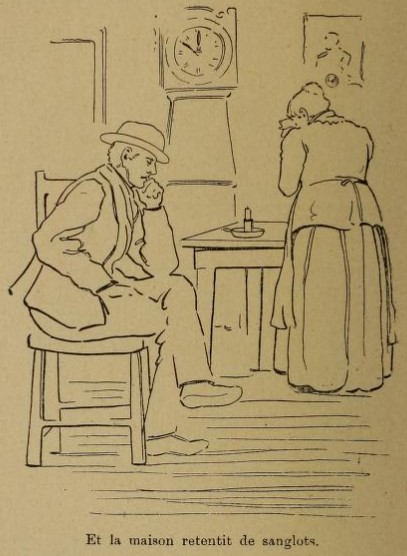

Tremblay journeyed the five miles back to his wife and their small, rocky plot. The initial feeling of relief quickly dissipated. Day after day, he would hear neighbors remarking on the rapid progress on the construction site. And as the bridge went up, so did his sense of dread—how big, exactly, was this debt he had assented to? Where would the man take him? For how long? His wife saw him become more agitated and, day after day, sought to extract the truth from him. Using every device under the sun, she finally won a confession. “You fool!” she cried out. “Don’t you see you made a pact with devil?” She asked how much time was left before the devil came to collect his debt. A teary-eyed Tremblay stated that his new master would visit by the end of that very day.

Darkness fell. Husband and wife sat by a flickering candle at the kitchen table, awaiting l’heure fatidique. They heard the knock shortly before midnight. Tremblay’s wife went to the door and the tall stranger greeted her with a long, almost mocking bow. “The time has come, madam,” he said, no further explanation being needed. “I beg you,” she cried out. “Give us only a few more minutes.” She turned around, looked at her spouse, sitting miserably at the table, and turned back. “See that candle? It is almost at its end. Give us the time that’s left in the wick, that we may say our proper goodbyes. Once the candle has burned through, he will be yours.” Having gained a soul, the devil confidently accepted. It was Mrs. Tremblay’s turn to smile.

She quietly walked back to the table and, standing between the two men, blew out the candle. She looked to the dark presence in the doorway, now framed only by the soft glow of moonlight, and stated, “You will never have my husband, for this candle will never burn again. Now be gone!” And with that, the ground shook violently and the devil was swallowed up.

The candle was buried, the bridge remained, and Tremblay found success in subsequent endeavors. But it seems the stranger continues to search, in these parts, for a soul to make up for the one he lost that night—a loss that shows that women have always been cleverer than the devil.

* * *

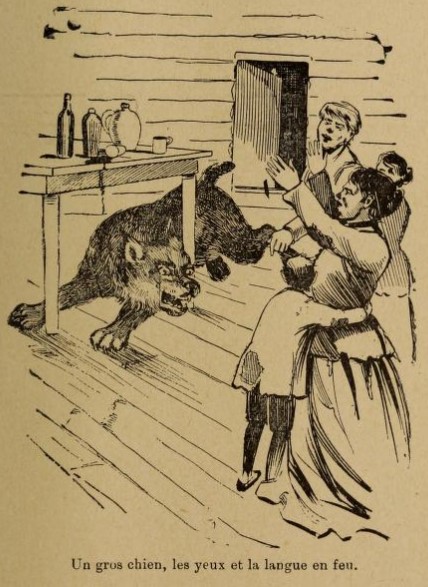

Like so many other societies, Quebec has historically had a rich mythological universe involving revenants (ghosts), talking animals, werewolves, witches, and lutins (elves, gnomes). But no character makes appearances as frequently as the big guy—the devil.

In the early modern Protestant world—and this still holds for some sects today—, anyone can fail to meet Biblical precepts and fall prey to temptation and sin. Evil is part of this world, but, aside from witches, few people have direct encounters with a corporeal Satan, who tends to be relegated to a different world that lies beyond death. That this fallen angel is a distant figure does nothing to lessen the danger he poses.

By contrast, from common folk tales, we might easily think that in Catholic Quebec, the devil is just a regular guy who wanders from one village to the next to stir up trouble—and whose efforts are regularly thwarted. This folkloric universe seems to confirm the old adage that proximity breeds contempt. Satan is taken out of Biblical and theological contexts and becomes a mundane figure. This is not the view expounded in Catholic teaching, but an adaptation that we find in French-Canadian popular spirituality. (Frank Abbot explores how that popular spirituality complemented official theology more than it contested it.) French Canadians, drawing on much older European traditions, purposefully refashioned the devil into a laughing stock. As in Rouleau’s story, Quebec’s devil can be outwitted, and folk tales have upheld popularity morality by celebrating cleverness and showing cases of just deserts. Tricks like Mrs. Tremblay’s provide comfort and challenge the apparent randomness of the universe.

The story above might have been told merely to entertain, or to provide listeners with a sense of control over their destiny. We can still detect lessons that would have spoken to the traditional values of a rural society. The conclusion is particularly effective because it can be read in two ways. Perhaps the storyteller means to say that one should beware of women due to their cleverness—or yet that a discerning, upright woman is the foundation of a strong household. Or is the story a warning against the silver-tongued devils of this world and foreigners (or strangers)? Is it a longer, more entertaining way of stating, careful what you wish for? Or be grateful for what you have? The tale’s specific meaning would have depended on the context in which it was told and the storyteller’s emphases, but it is worth noting that these varied interpretations are all in line with traditional French-Canadian self-conceptions. Today, this kind of folklore remains a valuable glimpse into the mindsets and customs of a society that has since been refashioned wholesale.

People like Beaugrand and Rouleau could not have been farther apart politically—Beaugrand being more than once made to be in league with the devil—, but, across their different emphases, their shared commitment to the making and remaking of Quebec literature helped give new life to a rich heritage. We should take a leaf from their pages as literary traditions are again at risk of being lost.

For more English translations of French-Canadian folklore, check out the incredible work done by Prof. Elizabeth Blood and her students at Salem State University.

Having being away from my French Canadian family for nigh on 65 years, I am amazed as how the rhythm of the tale fits right in. I am also amazed as how the written words (French) can be picked up so easily. I never spoke French as a child. My parents did and it was usually fighting words hurled across a supper table.

But, alas, pull away the grey hair, you will find a young pigtailed French Canadian, loving to hear the folklore of old. Thank you.

This is a great analysis of the tradition of folktales in French Canadian culture. I love how you leave the meaning open to interpretation. And thanks for the shout-out at the end!

Pingback: An Introduction to French-Canadian Folklore & Franco-American Culture – Moderne Francos

That really is a great story. Thank you very much for sharing it with us.