Honoré Beaugrand was a prominent supporter of the Liberal cause in Canada. He left his mark on the Quebec press as the founder and proprietor of La Patrie. He faced down rioting anti-vaxxers as mayor of Montreal in 1885. At last, in Franco-American circles, Beaugrand is best known as the author of Jeanne la Fileuse, the first widely circulated novel about the French-Canadian immigrant experience.

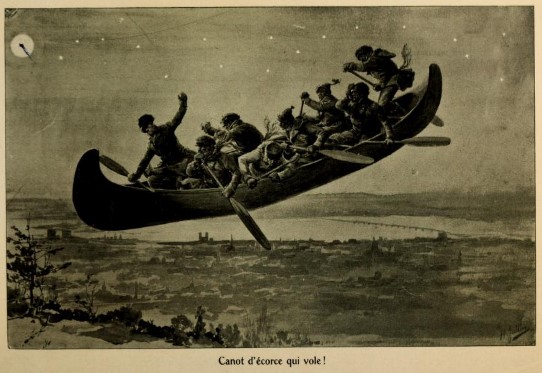

Today, however, the blog turns to Beaugrand’s efforts to preserve—in writing—French Canadians’ most cherished oral traditions. Some of that folklore appears in a collection of short stories titled Légendes canadiennes; though Beaugrand was credited as the author, many of these stories had been around for generations—maybe centuries—and were preserved with various regional inflections across the province. The most famous of these is La Chasse-Galerie.

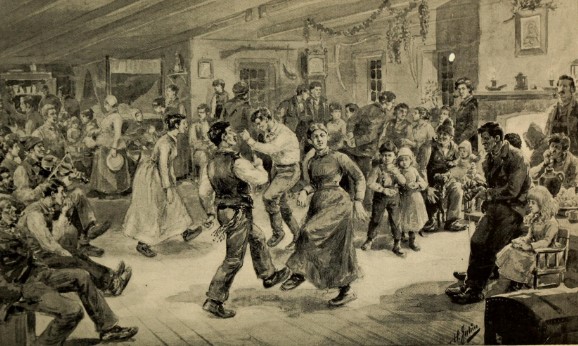

The folk tale that I share below did not appear in the Légendes. Rather, it fits rather awkwardly in the first half of Jeanne la Fileuse, while our main characters still live in Canada. It is the local schoolmaster who shares it at a springtime gathering celebrating the return of young men from the chantiers, the lumber camps of the Ottawa region. But this schoolmaster recounts the legend as he himself heard it from Old Man Hervieux during the winter of ’58. We have, in essence, a story within a story within a story.

Here, then, is the morality tale known as “Le Fantôme de l’avare,” the pre-industrial, French-Canadian counterpart of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol—though as you will see, the events take place on New Year’s Eve. The approximate translation is my own. For more on the French-Canadian Christmas and winter holidays of Quebec, see this excerpt of Prosper Bender’s work.

Every year since the days of my youth I’ve been asked to recount those frightening moments I experienced on the road to Lanoraie many winters ago. I am grey and hunched, now, and this may be the last time I have that opportunity. As you leave the warm glow of my hearth, tonight, remember the terrible punishment to be meted out by the hand of God to he who will not open his door to travelers in distress.

My father had sent me out to Montreal to purchase holiday provisions. Most important of all was a small cask of Jamaican rum, an absolute necessity were we to treat our guests properly on New Year’s Eve. By mid-afternoon on that fateful day I had completed my errands in the city. Eager to be home by nine o’clock, I kept my horse in a lather. When I reached the north end of the island I could see the clouds gathering. It was already snowing heavily when I approached Repentigny.

I’ve seen some awful snowstorms in my time. None do I recall being worse than the one I faced on that day. There was no sky, no ground. The road disappeared just as dusk fell. I passed the church of Saint-Sulpice—but beyond, I went on blindly in the snow. Some time later, thinking myself in the neighborhood of the Robillard farm, I hopped down from the buggy and tied my horse to a fence post, which at least hinted at a human presence. I meandered on foot for a few minutes until small points of light broke through the wintery drape. Was this a mirage? Slowly I pushed through and the outline of an old farmhouse came into focus. I didn’t recognize it, which I could not understand. I knew every house along the King’s Road—if this was in fact still the King’s Road.

As I walked up to the door I saw that a roaring fire was burning within. I could not believe my good fortune. Shivering uncontrollably, I had started to believe myself lost to the storm. I introduced myself when a voice answered my knocks with the traditional Qui est là? The man who let me in was as old as I am now—no, much older. The hand he extended could well have scorched me. The heat was overwhelming and, though the fire was safely confined to the hearth, it is as though the entire house was aflame.

The old man took my ceinture fléchée and my coat of homespun while offering his welcome. I explained in a few disjointed words that I seemed to have lost my way. He served me a warm punch and showed me a chair by the fireplace. He went out to fetch my horse and buggy and place them safely in his shed.

Breathing heavy sighs of relief, I began to take in my surroundings. Hunting trophies were poking through every wall. A hunting gun surely dating to the French regime was perched on a rafter. In a corner, a bench covered in bear skins was likely all that the man had for a bed. And the only seat beside my own was a worn oak log.

Who was this man who lived so sparsely? If this was Saint-Sulpice, how was it that I did not know him? I was still confused when he returned and silently took his seat by the fire. I asked his name. He slowly turned towards me and I instantly recoiled under his gaze. There was something odd and unnatural, something very powerful in his eyes—they were not merely reflecting the dancing flames, but casting their own light.

I felt myself shrink in my seat, so unnerved I was. And yet, I found the strength to ask again. He drew closer and extended his bony hand to my shoulder before looking away. I could feel the weight of the silence. Then he began:

“I do not wonder that I seem a foreigner to you, for you are a lad not yet of twenty. There was a time, long ago, when I was the richest man in these parts. This was well before the English arrived. I was then known as Jean Pierre Beaudry. I had done well in life, but the wealth I acquired I kept all to myself. There came a stormy winter’s day, just like this one. I was here—warm and self-satisfied. And I heard a knock at the door. You see my wealth was the measure of everything and I instantly feared that I might let robbers into the house. I did not open. The knocking stopped and I fell asleep by the fire.

“I was awoken by the greatest commotion on my doorstep. I recognized the voices—young men from a neighboring farm—so I quickly went to the door to upbraid them for the racket they were causing. I didn’t have the chance to say a single word. As I opened, my eyes immediately fell on an inanimate body that had been claimed by the snow and arctic winds. Thinking only of myself, I had left a poor traveler to perish. My sins had come knocking and now lay naked to the world.

“Seized with remorse, I decided to give away my entire fortune to the poor of the parish. Every day I prayed for forgiveness and hoped that God would see my sincere contrition in this act of charity. Only two years later, I was burned to death in this very house.”

Beaudry paused. Those last words hanged uncomfortably. The heat of the fire now felt downright oppressive.

“I stood judgment before the Creator. I was not worthy of His eternal grace. I have lived in the flames of purgatory for these past fifty years—all but for one day each year. Every December 31, I have returned here, in this form, so that I may make amends. I have waited for the visit of another lost, lonesome traveler in need of hospitality, the kind of hospitality that I refused when I lived in this world, that I might prove myself worthy of joining the saved and the saintly. Not once in fifty years have I had that opportunity—until tonight.

“In losing your way, tonight, you have saved me. I am free.”

I have no other memory of that which transpired that night; I suppose I then fell asleep. But when I awoke it was still nighttime; I was in my buggy, in sight of the church of Lavaltrie. The storm had begun to lift and the road was again visible. Terrified, I drove my horse hard until I reached the old homestead in Lanoraie, some time after midnight. My worried father had stayed up and greeted me at the door. When he heard my tale, he gathered the entire household in the common room; we knelt and he led us in prayer. Not a year passed, from that point on, that we did not gather on New Year’s Eve to pray for wary travelers who, tossed in the storm, suffer and lose their way.

Some weeks later, on an errand in Saint-Sulpice, I happened upon the local vicar and asked whether he knew of any Beaudry in the area. He thought for a moment. “There was a Beaudry where Pierre Sansregret built his farm,” he explained, “but that’s forty years past at least. The old men still speak his name. Of course, that’s of no help to you. This Beaudry is long gone, having perished in the fire that consumed his home.”

Now, at least, the miser’s ghost truly belonged to history.

Leave a Reply