The story of the commercial embargo on Lake Champlain continues with E. A. Kendall. See Part I here.

“I was in pursuit of no palace for my lodging; but, even I was destined to adventure. On the Province Point, on the north side of the boundary, I was taught to expect to find a store, inhabited, and in the bustle of the running business. We reached, at length, what the boys pronounced to be the Province Point, and, on drawing near, we saw a log-hut, but in which there was no light. We landed, and found ourselves in a solitude. From this spot, however, as my conductors assured me, a walk of half a mile would carry me to a public-house; and, here, therefore, they proposed to leave me, being themselves fearful of going round the point. It happened, that I was without change, to pay the reward agreed on for their service. I had relied upon procuring this at the store, and now proposed, that one of the party should accompany me to the public-house. The others were afraid to wait for him; and, at the end of the few moments which elapsed in this conversation, we heard a second canoe, paddling to the shore. At the sound of our voices, it drew off; but, on our speaking to those who were in it, and assuring them that we were friends, it came to land. It happened to contain a gentleman, whom I had previously known, a Boston merchant, who had succeeded in carrying forty thousand dollars in specie, into Canada, and who was returning with the bills on London for which he had sold them.

“He, like myself, was to be carried no further than the Province Point, and I was now to have a companion, on my journey to the public-house. As, where we stood, the path that we were to take was not very obvious, we advanced a few steps, to explore it; but, in so doing, we found, at a very few paces back, that the land was overflowed, and that we were placed, as to all purposes of walking, only upon a diminutive island. I had now reason to rejoice in my want of change; for, so pressing were the fears of my crew, that had I been able to give them money, at the moment of landing, they, at the same moment, would have retired with precipitation, and I should have been left to pass the night at the boundary-stone.

“Upon this discovery, it was admitted to be indispensable, that the canoes should turn the point; and the soldier in mine, with that civility of deportment which I have often had occasion to admire, in the privates of the British army, warmly declared that he would run all risks, rather than not set me on firm land. Having turned the point, we made a further arrangement, for proceeding at once to the public-house, a task which we happily completed.

“The public-house was kept by one Rouse, and stood on a second point, called Rouse’s Point. It was a small building, and in no situation for the enjoyment of large business, except from the actual condition of the country. I found it crowded with adventurers in the unlawful trade, for whom it was a rendezvous. Its contiguity to the limits of Canada rendered it convenient, for those who, as opportunity afforded, carried their goods into the province. The custom-house boats spent the night in cruising in the mouth of the lake, and their absence from this shore was to be watched, and turned to advantage.

“Stories are continually told, of the comfortless lodgings afforded to travellers in the United States; but, in all parts of New England, even those the most recently settled, I had been oftener led to admire the good accommodations which I found, and the furniture and manufactures, which industry, enterprise and economy had accumulated, sometimes in very remote situations, than to make any contrary reflection. In particular, a practice has been mentioned, of lodging two or more travellers together. Nothing of this kind had ever yet fallen in my way; but, I was now, not in New England, but in New York; different manners, as I had been led to believe, existed in these quarters; and, at least, the peculiarities of the times and situation were, in this instance, such as might have apologized for almost any thing. In a very small house of logs, I saw at least twenty men; I considered I was so abundantly clothed as to be independent of every accident for the night; and I resigned myself, without a word, to all that was to come. To my surprise, not less than gratification, the mistress of the house so disposed her numerous guests and family as to leave the best room and a four-post bedstead to myself. The room was the common eating-room; and, in the morning, when I was awaked by some voices speaking French with a strong nasal accent, I found the curtains carefully pinned round the bed.

“Rouse’s Point is part of the town of Champlain, in which certain Canadians and Acadians, who, by joining in the rebellion of the colonists, had forfeited their allegiance, received grants from the United States. It has been said, that the settlement, formed by these people, was subsequently broken up; but, though this may in part be true, many of them remain.

“To reach Burlington, I was advised to proceed first to Chasy [Chazy], a settlement six miles to the southward of Rouse’s Point, and where there was a probability of meeting with some vessel about to cross the lake. For this voyage, I hired a canoe. . . .

“Our canoe discovering itself to be leaky, we put ashore at the custom-house, which stands at less than a mile from our place of departure, and where there were about forty militia on parade. They were not uniformed, and their situation was as uncomfortable, as their appearance was little respectable. They were the objects, to all the country, either of execration or derision. On the peninsula and a burgh which forms the opposite bank of the lake, there was another custom-house; and, at a point of land on the peninsula, called Windmill Point, another garrison.

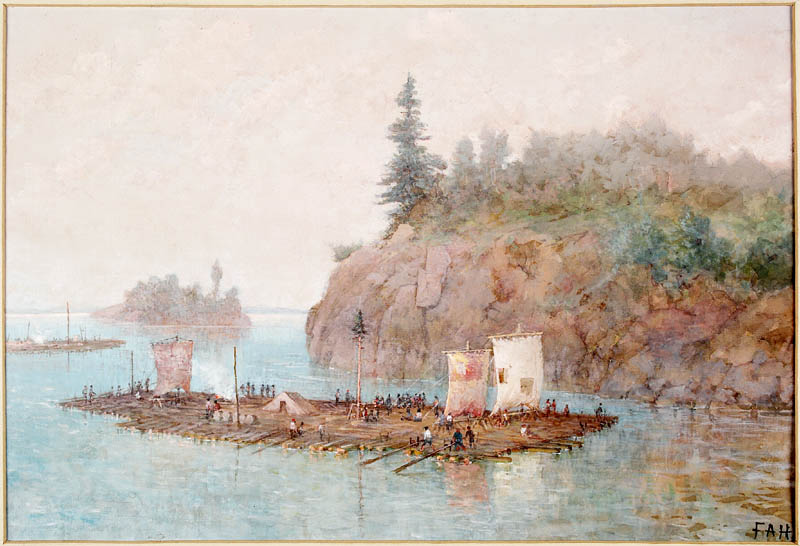

“Within sight of the custom-house, and under Ile de la Motte, lay a raft of masts and lumber, said to be three quarters of a mile in length; and there was a second raft also in sight, lying under the shore of the peninsula. In these rafts consisted the enemy of which the two garrisons were in watch. The former had no other destination than Quebec, and they were waiting only for a south wind, in order to be floated into Canada. Their captains and crews had wooden cabins or houses upon them, where they lived during the time spent, but they were yet frequently on shore. Nothing short of battle was hourly looked for, and both sides were prepared. On the raft, there were breast-works formed of logs; and the conversation of the people, and particularly of my canoe-man, who was to fight on board one of the rafts, ran entirely on how many men would compose the crew, and on what quantity of ammunition was in the magazines. . . .

“At Chasy, there is a village, with a wharf and warehouses, and some appearance of business. In reaching it, we passed Point au Fer, near which are the remains of a fort. Between this point, and Point aux Pommes, which is to the southward, is a bay, in which, and particularly on the points, the lands are said to be good. Along the shore, where there are inhabitants, there are usually potash-works, potash being one of the staples of these recent settlements.

“The inhabitants of Chasy are in great proportion Canadian, many speaking only the French language, and many, though speaking English, having French names. Of the latter class is the landlord of a very decent inn, kept at the head of the village. There was a sloop loading at the wharf; but, as she was to wait for an opportunity of escaping the vigilance of the custom-house, I was compelled to seek for another mode of conveyance. Two Canadians were accordingly mentioned, by whom I could be rowed across the lake. While I waited for their coming, I strolled away from the inn; and, on my observing to my landlord, on my return, that I had not yet seen the Canadians, I was answered, “How the hell should you, when you were out of the way!” At this time, I had been so long used to the polish of the Canadians, as well as to the decorum of New England, that the expression coming, too, as it did, from one of a French name absolutely startled me, as something unnatural. It was said, however, without ill humour, and was a token only of the coarse manners of the country.

“Between Chasy and Burlington, the course is south-east, and the distance thirty miles.—The day was exceedingly fine, but without wind in any direction, and the lake was one smooth sheet of water. Incapable, therefore, of deriving assistance from their sail, the Canadians were constantly at the oar. We left Chasy at one o’clock in the afternoon, and did not reach Burlington till near twelve at night.”

Source

Edward Augustus Kendall, Travels Through the Northern Parts of the United States, in the Years 1807 and 1808, Vol. III (New York City: I. Riley, 1809).

Leave a Reply