Emigration was political. Most late nineteenth-century French-Canadian emigrants left Quebec for economic reasons. But there were political causes underlying the province’s economic woes; efforts to stanch this demographic hemorrhage and to repatriate the exiles inevitably reverberated into partisan politics.

Early reports on emigration to the United States (issued in 1849 and 1857) suggested solutions; policies implemented in the 1870s and beyond were too little too late. By the end of century, despite the best intentions of some leading figures, large-scale repatriation had failed to materialize and only economic slowdowns in the U.S. had deterred French-Canadian emigration.

For the first thirty years after Confederation, the Conservatives seemed to be the natural governing party in both Ottawa and Quebec City. Liberals found it convenient to politicize emigration—as it deserved to be, considering its scope and effects.

Enter Beaugrand, a liberal and a Liberal. The Liberals had been skeptical of Confederation from the moment it was proposed. They were scandalized by patronage, expensive infrastructure projects, evidence of graft, and limited economic growth. Doubts about the merits of the existing constitutional and political arrangement peaked in the 1880s, with good reason. Prosper Bender’s work is evidence of that. As Jeanne la Fileuse shows, there was ample cause for dissatisfaction in the 1870s.

In addition, Beaugrand prefaced the second half of the novel with excerpts of “La Voix d’un Exilé,” a poem by one-time annexationist Louis Fréchette. Both the poem and the tenor of the novel offer a compassionate view of the emigrants and an account of the United States that is far from a land of eternal perdition. (The poem anticipates Emma Lazarus’s most famous work, which was to be immortalized in bronze.)

Without further ado, I give you the remainder of Beaugrand’s political digression.

~ ~ ~

When American industrialists became aware of the work ethic and frugality of the French-Canadian laborer, and when they compared his soft and peaceable character to the turbulent and bellicose spirit of the Irishman, these industrialists came to understand the worth of his services. Each Canadian family arriving in the United States became a means of propaganda and information for family and friends in Canada. People who had until then known only misery and privation suddenly found themselves in a relatively sound position; the father, the mother, and the children generally worked in a single factory and the combined wages of the family amounted to what seemed like a small fortune at the end of each month. They would write to the native country—to a brother or sister, to a cousin, to friends in the old village—and the migration grew in proportions daily.

Canadian ministers didn’t even bother to inquire into the causes of this mass departure of the French population, let alone seek to find a remedy to circumstances so damaging to the interests of the French nationality in Canada. No, indeed: they were then busy working to amalgamate in a general confederation all of the British possessions of North America. While French Canadians were travelling to the United States, asking for work abroad, the statesmen were travelling to England to sell at the Court of St. James—in exchange for titles and medals—what little influence the French-Canadian nationality still possessed. We have placed the busts of such men on the altar of the homeland, and we have written their names into the pantheon of a certain political party, but we have forgotten to hold them accountable for their inaction on the agricultural and industrial concerns of their indigent compatriots. They indulged in English politics and organized as best as they could the provinces of this new power, but they forgot the Canadian peasant who was being chased away from the farm by suffering and hunger. The placemen found their way into the new federal administration; career politicians became ministers; the leaders became baronets; party hacks now served as informers for customs and the police; and the honest family man sighed as he went into exile, wondering where all of the taxes and public funds were going—wondering also what exactly the purpose was of having these ministers of agriculture and commerce in Ottawa and Quebec City.

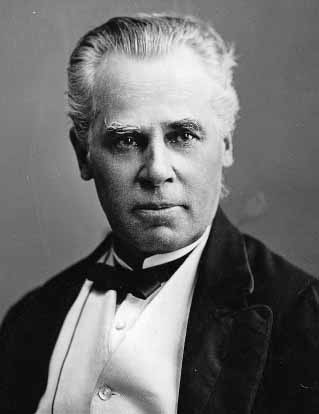

Was it not one of these men, the great architect of Confederation [George-Etienne Cartier], a man who made a principle of servility, who said of Canadian emigration:

– Don’t bother; it is but the rabble that is leaving. The good people stay and the country will be better for it.

The name of this man was entered into the rolls of the titled servants of England. The “rabble” to which he arrogantly referred can be happy, today, despite the sorrows of exile, to be severed from the shame of its political past.

The torrent of emigration increased constantly and the cities of Fall River, Worcester, Lowell, Lawrence, Holyoke, Haverhill, and Salem, Mass.; Woonsocket and the villages of the Blackstone valley; Putnam, Danielsonville, and Willimantic, Conn.; Manchester, Concord, Nashua, and Suncook, N.H.; Lewiston and Biddeford, Maine, in short all of the industrial centers of New England were invaded by an army of Canadian workers who brought as their only means their habits and love of work. While the knight-ministers of Canada were scrounging for power under Confederation, American industrialists were building new factories. New England had become a giant workshop where all of the Americas’ necessities were produced. French Canadians lured by the marvelous news they were receiving from family and friends came in larger numbers. They received their share of work, they were well-paid and well-treated, and it is only by comparing the state of commerce and industry in the United States and in Canada that we see why five hundred thousand people would have left home to ask to be welcomed in a foreign land.

The French-Canadian emigrant comes to, and stays in, the United States because he can win his daily bread more easily than he does in Canada. That’s the simple, unvarnished truth. […]

Leave a Reply