It has become a rite of passage for any scholar of Franco-American history to address the report issued by the Massachusetts Bureau of Labor Statistics in 1881. The Bureau was one of many publicly-funded agencies created in the late nineteenth century to provide policymakers with information on industrialization, urban life, the workforce, and general economic conditions. Colonel Carroll D. Wright led this particular agency for years and he earned the opprobrium of Franco-Americans in 1881 when identifying them as “the Chinese of the Eastern States.”

The connection might seem strange from the vantage point of the twenty-first century. Wright was equating French-Canadian migrants with a marginalized, visible minority that would soon face curtailed immigration through the Chinese Exclusion Act. He added that they were highly mobile and had little or no attachment to U.S. institutions; they kept apart from the mainstream and would not melt into the American cultural casserole. Franco-Americans vigorously protested. In light of the times, Wright was remarkably obliging in hearing their concerns in person—at the State House in Boston no less—the following fall. (See here for a summary of the entire episode.)

Wright included Franco-American testimony in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ next report. But by no means had his apparent generosity resolved big questions concerning French Canadians’ values, economic role, and allegiances. In fact, politicians and labor leaders resurrected the main contentions of the 1881 and 1882 reports during a federal inquiry into labor relations in 1883. Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Education and Labor, in Washington, D.C., a young printer and labor leader from Cambridge, Massachusetts, relied extensively on Wright’s recent reports.

Frank Foster, affiliated with the Knights of Labor, was questioned over the course of several days in February 1883. Though perhaps not the best-informed observer of industrial conditions, by virtue of his occupation, Foster provided the committee with a glimpse of conditions in the textile industry, paying special attention to the respective conditions of American and English textile workers. He also brought the issue of female and child labor in the mills to the fore. His testimony and that of other labor organizers helped to place the concerns of workers—as well as employers’ abuse of power—on the national agenda, a rare opportunity to redress the uneven relationship between capital and labor at the height of the Gilded Age.

Foster was sincerely committed to worker rights. On the surface, his commitment to a more equitable society was laudable. But late nineteenth-century labor organizations had, like later progressive groups, their blind spots—especially in regard to ethnic and racial minority groups. Foster made that quite clear when drawing extensively from Wright’s last two reports. He quoted the Bureau of Labor Statistics to provide a glimpse of living conditions in textile companies’ tenements before referring to “the Chinese of the Eastern States.” Foster acknowledged the forceful statements of Franco-Americans leaders in Boston, in the fall of 1881, in response to the disparagement of the Canadian immigrants. But it was the better sort who had testified, he declared. Said Foster, “[Wright’s] argument remains, I believe, in the view and understanding of most of the people of New England, substantially sound and unshaken by the testimony that was adduced at that hearing.”

The young printer reiterated the main claims of the 1881 report, declaring that French Canadians saved wages earned in the U.S. and aimed to “invest their money in the land, buy a farm, and settle down ‘at home,’” i.e. in Quebec. He cited as evidence the existence of a repatriation society, which he called an “anti-colonization society,” under the control of Catholic Church north of the border.

Committee members were intrigued. They asked whether there were concentrations of French Canadians, living long enough on U.S. soil to form distinct communities. Foster answered that

That is sometimes the case in the larger towns, and, as I stated before, it is very often their custom in the smaller places to occupy a section of the town by themselves, several rows or blocks of houses. I know that in many villages I passed through I was told that such a portion of the villages was the French quarter, or ‘French row,’ or ‘French block,’ or whatever name of that kind might be given to it.

The witness brought a table showing the population makeup of thirty-two cities, towns, and villages where the Canadiens were present in large numbers. The table showed a total of 88,653 French Canadians, more than one-fifth of these communities’ aggregated population. Evidently policymakers could not afford to ignore this element.

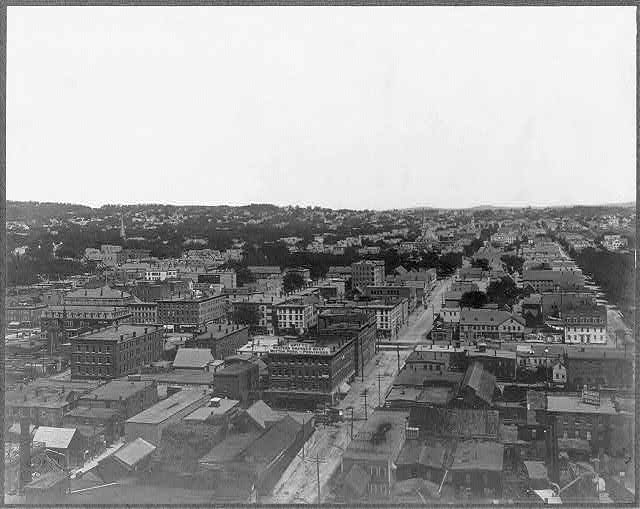

In the summer and fall of 1883, the Senate committee travelled extensively to obtain a better sense of local conditions, going as far north as Manchester, New Hampsire, and then south to Alabama and Georgia. An interesting exchange during hearings in New York City indicated that business interests could prove more reliable allies to French-Canadian immigrants—at least in their rhetoric—than the more overtly nativistic labor leaders.

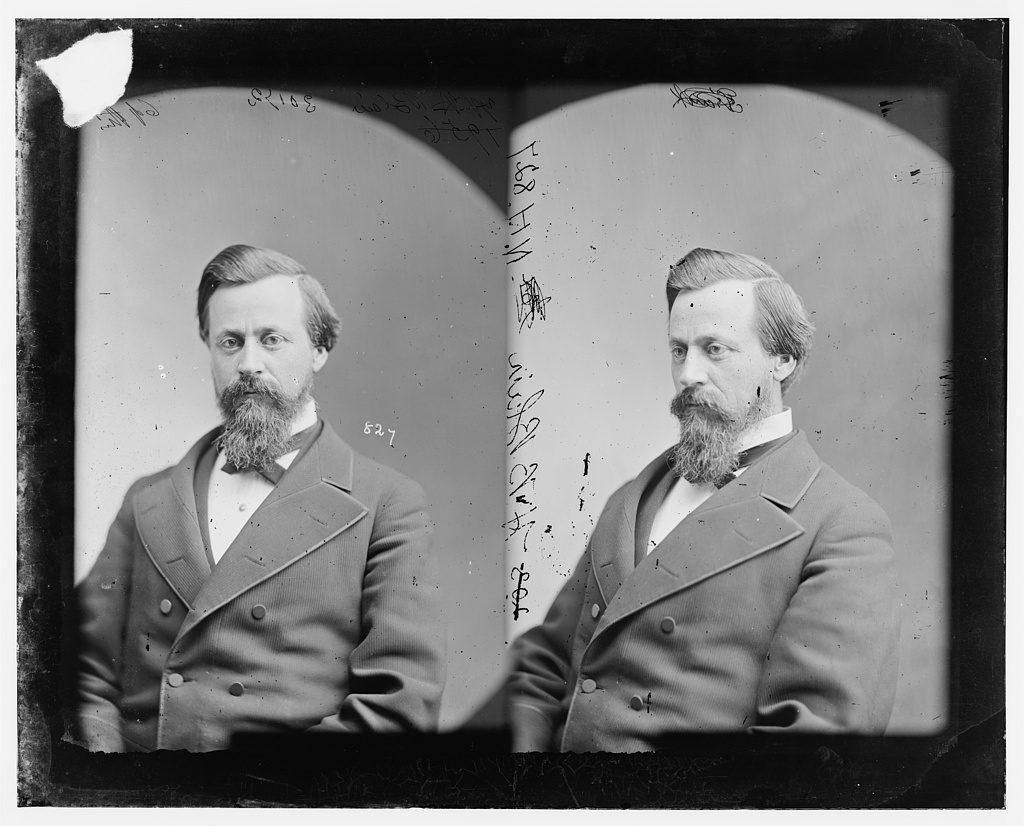

It just so happened that the chairman of the Senate committee was Colonel Henry W. Blair, Republican of New Hampshire, who from personal knowledge of the immigration situation in his home state, insisted on French Canadians’ increasing dedication to the host society. While interviewing P. J. McGuire, a New York labor official, Blair spoke for the Canadians:

I want to say at this point, since the French Canadian and his status in New England are spoken of so often, that of late he is becoming more and more a real-estate owner, and is looking more to a permanent residence in the country that he has adopted.

“The percentage of that class is small,” replied McGuire. Blair continued:

It is increasing. That is all I say about it. I do not mean to controvert the general force of your statement. There is an improvement in that regard, and if you go to Manchester, Suncook, Great Falls, and those various manufacturing places where the French Canadian is employed you will find that he is there with his family and his little school, and that he owns a little property, probably, and intends to stay.

In Manchester, an industrial city still without organized labor of any significance, testimony on French Canadians became much more positive—thanks in part to the presence of mill managers and a Catholic prelate at the October hearings.

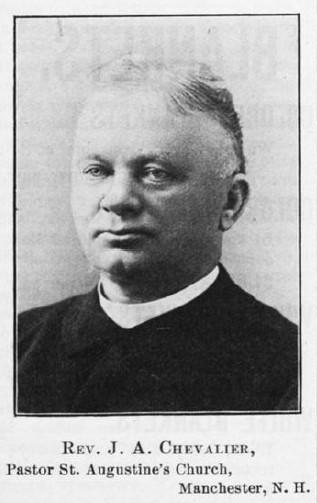

Charles McDuffie, representing the Manchester Mills, offered a friendly portrait of the Canadians. But it was arguably the testimony of Rev. Joseph Augustin Chevalier that was most noticeable. Perhaps out of Christian charity, Chevalier declined the opportunity to rebut statements previously made before the committee by specific individuals. Instead, he acted as a spokesperson for his parishioners and the larger French community of Manchester, expressing their interests and concerns.

French Canadians were coming to the United States to improve their lives, he declared. He insisted that low wages and the state of tenements prevented them from doing so. But his overall view differed in significant ways from Frank Foster’s. With reason: these hardworking migrants obeyed their priests and opposed strikes. As noted elsewhere, they were a conservative force in the labor landscape of late-nineteenth-century New England. Despite recurrent efforts to integrate them into a strong, cohesive labor movement, the Canadians remained apart: they wished to avoid disorder, and to avoid losing wages or risk expulsion from the tenements.

Chevalier provided signs of acculturation among the migrants. Children born in the United States or raised in this country from an early age easily picked up English and generally preferred it outside of the home. Families often lived too immoderately to save up and settle in Quebec. Although many claimed a desire to return to Canada, effectively few did. But, one committee member asked, “do their leaders and clergymen and others that have influence with them encourage them in the idea of remaining and being permanent citizens here?” “Certainly,” the prelate answered, afterwards confirming that that was his own “personal desire.” Of course, the Church in Quebec would have questioned this desire—its repatriation efforts in fact providing steam to statements like Wright’s and Foster’s.

The most striking aspect of these hearings in Boston, Washington, and Manchester, in the 1880s, may be their circuitous nature. More so with French Canadians than the Irish and many other groups, debates on their commitment to the United States and involvement in organized labor had a long life. Although much changed in American life from the 1870s to the interwar period, the questions raised by a Franco-American writer in 1924 were reminiscent of the language used in public hearings nearly two generations earlier.

The proximity of Quebec and the inability of elites north of the border to stanch the expatriation of French Canadians had much to do with this. Families did acculturate and rise in socioeconomic status, but a near-continuous influx of French Canadians in the United States (with dips in the 1870s and early 1900s) reinvigorated debates for the better part of a century. Far from suggesting a perpetual “apartness” from mainstream U.S. society, this serves to highlight the perpetual relevance of events in Quebec to the course of life (not least in labor) south of the border.

Bibliographical Note

The four-volume report “Testimony on the Relations Between Labor and Capital” issued by the Senate committee in 1885 is available in separate parts on Archive.org and HathiTrust.org.

Britannica paints a generally rosy picture of Senator Blair’s reformist impulses. Gordon B. McKinney’s Henry W. Blair’s Campaign to Reform America: From the Civil War to the U.S. Senate (2013) provides a glimpse of Blair’s relationship with French Canadians, who became a natural constituency for Republicans, in opposition to the predominantly Democratic Irish. (Ignore the Google Books description, which is actually of a different work; much of the book on Blair is available online.) McKinney notably addresses the hearings of 1883. He also authored a more focused study of those hearings, which appeared in Historical New Hampshire in 2001. In a fascinating twist, following his Senate career, Blair was appointed ambassador to China. His involvement in excluding the Chinese (not “of the East”) from U.S. shores led that kingdom to exclude him and declare him persona non grata.

Leave a Reply