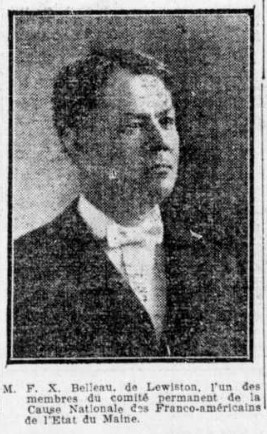

Charles Edmond Rouleau attributed a litany of moral failings to expatriated French Canadians—they were lazy but also greedy, improvident and very often intemperate, they betrayed their homeland and their faith. As the nineteenth century wore on, this type of rhetoric, tending to leave Franco-American communities to their own devices, became dominant among Quebec elites. I have found relatively few direct Franco-American rebuttals to scathing attacks of this kind, which is not necessarily to say that there were few. The following piece, written by François-Xavier Belleau nearly thirty years after Rouleau’s work appeared, is as strong a statement as I have yet come across. It highlights the profound strains that had developed between cultural elites on either side of the border in the intervening time.

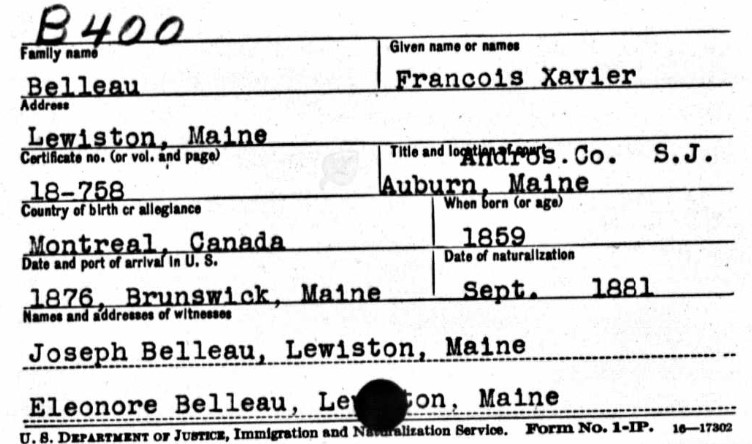

Belleau was born in Montreal in 1859 and came to the United States—first to Brunswick, then to Lewiston, Maine—at the age of 17. Although naturalized in 1881, he did not abandon all ties to the homeland. He married Blanche Martel in Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec, several years later and one of their sons would go on to study in Sherbrooke. A career in law led Belleau to serve in municipal offices in Lewiston in the 1880s and 1890s. His election to the state house in 1892 was even reported in La Presse, in Montreal. For four years, perhaps as a reward for his work for the local Democratic Party, he served as U.S. consul in Trois-Rivières.

He also took an active part in the life of his Franco-American community, notably serving as president of the Club Musical-Littéraire of Lewiston. In 1901, he attended the Franco-American convention in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he emerged as a voice of caution amid dramatic speeches condemning the “Irish Church.” In 1906, he was invited to join the permanent committee of the Cause nationale, which sought to protect Franco-Americans’ cultural rights within the Catholic Church in Maine.

March 14, 1906 (BAnQ)

In short, Belleau was neither a hardline Americanizer, nor an uncompromising son of Quebec. His words remind us that the Franco-American identity was a fusion of different elements, an identity open to diverse definitions and interpretations that are still with us nearly a century later.

Notice, in particular, his desire to quell the rampant nativism of the 1920s not merely by “Americanizing” in a cultural sense but by using the ballot box to Franco-Americans’ advantage.

Always Repatriation

La Justice (Biddeford), December 19, 1924[1]

Sixty years have passed since our element made its first mass appearance in the cities of the Republic’s many states. Sixty years and more have passed since the beginning of this emigration to manufacturing centers where today we are reasonably well established, making a good life, as the young man says, and entirely at home and at peace with everyone.

Why should we not be satisfied to be free citizens benefiting from all of the privileges given to us by one of the greatest political charters ever devised?

It is in this country that we were truly welcome. It was to this country that we came, without any extensive preparation.

A people never migrates without reason. At the time we were leaving the homeland, there were few industries. Only agriculture could have retained us. I have said it once, and again I say, not everyone is made to be a farmer. As honorable as it may be to plough the fields, no where do we find a providential decree suggesting that we ought to be an agricultural people in America, any more so than other races. We were justified in traveling to the United States—we now see convincing proof, but this mass exodus has met with strong opposition from Canada’s notables.

The federal government, the local government of the time, statesmen, some in the press, and other important influences quite naturally deployed all means to halt this movement. But nothing could slow its momentum. The movement became absolutely unstoppable and on the whole irresistible.

Popular reason—for all of the limits to their education and understanding, the common folk still have the right instinct and can discern—, knowing what is practical, good, and useful, saw through other arguments. People moved to the United States. As for those who did not see a need to emigrate, there weren’t two ways of looking at the situation; there still weren’t two sides to the story. In their eyes, this movement was unjustified. There was nothing good or logical to it. Language, faith, and customs—all would suffer for it. Emigrants were simply settling in a land of perdition. Providence had no part in it. Beyond the abandoned province, no new homeland awaited the race. To emigrate was to have one’s heart in the wrong place. For us there was nothing but a long sigh of desperation.

Some declared, “Poor Canadians who emigrate to the United States, your fate is sadly different from that of your brothers, who remained faithful to the homeland. You crumbled under the sacrifices that your country asked of you.

“How can you sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?”

So it was that those who had left and those who continued to leave were but poor, miserable exiles and traitors to the country that had brought them into the world.

That did little to improve the lot of those who still had no thought of leaving. Before long, as nothing improved, relatives of relatives and friends of friends talked and, in no time, people were in motion anew.

It was in this time that a great mind who shared in governing the country—whose role in French Canadians’ fate in Confederation led the English to rejoice—shamelessly declared, “Let them go, it’s the rabble that leaves.”[2]

The emigration movement continued.

As our friends could not see the work of Providence in our people’s emigration to the United States, they determined to repatriate them. Our friends sent agents after them. The constructive enterprise that was naturalization in this country met the destructive work called repatriation. Repatriation—that we still talk about. Repatriation—impossible, impractical, the cause of such instability, pain, and tears, which stole from people money they had earned from the sweat of their brow, when fraudulently won over to this cause.

Repatriation had no capital but false and exaggerated sentiments. It undermined everyone. For thirty years everyone held their breath while repatriation called us back to the homeland, when in fact the homeland has no specific place—in America, our race is everywhere.

Impossible repatriation, when will you be laid to rest? Is it not time to recognize that it helps no one?

In this country, too, railway agents, those who claimed to be our guides, and our leaders joined their voices to those in Canada and, to all who would listen, declared that naturalization was a crime, that our duty was to repatriate.

Our greatest mind, Ferdinand Gagnon, a repatriation agent, or a relative or friend of repatriation agents, declared in an address in Worcester:

“Patriotism calls on us to repatriate. United as brothers under the cross, our hearts filled with courage on the banks of the St. Lawrence, we will be as a new power that no political change, however brusque, will ever shake in its customs, language, and faith.”

This is how our people were asked to view American citizenship in this period.

Gagnon was not the only one to nourish such sentiments, which, noble though they might be, were but dreams and unachievable projects, as experience has proven.

We might as well have tried to repatriate the Irish. No one ever dared to suggest that. Jews now have an organization aiming to repatriate the entire race of Judea, I believe. It is not taking hold.

Yet it remains that such sentiments still exert among us great influence. It is precisely such sentiments that have kept, and still keep, our own in a state of indecision and indifference. At best, only one-sixth of our people are now American citizens. This is what empowers some elements in this country to call us “Fifty-Fifty.”[3]

Repatriation of our people is not a serious thing, but naturalization is possible and practical and should no longer be delayed. Certainly, naturalization faces challenges. People must go out of their way and spend both time and money. It is harder to gain citizenship now than it was, but it remains easier and more advantageous than to face deportation.

During the war years, thousands of our people took it upon themselves to declare their intention to become American citizens. And that was the end of it. A large number slumbered after this well-meaning act. Seven years have passed. Everything is to be started anew.

Perhaps repatriation wouldn’t do much harm if it seized all those who find nothing of use under the Republic, or who put off to tomorrow what they can do today. They lose neither time nor money by waiting. Alas, in some spheres, legislation is proposed that will eventually find a place on the statute books…

Several weeks ago, a French-language newspaper deplored the apathy some of us manifest in public matters and cried out, “Let’s wake up!”

Yes, let us wake up. Recent statistics show that there are in Maine 53,000 people not yet naturalized. There are 18,000 in Vermont, 205,000 in Connecticut, 78,691 in Rhode Island, and 547,497 in Massachusetts.

Are there some of our people in these states that fall in this category?

Is there anything to be done?

With some work, there isn’t a single state where we cannot increase our number of electors by the thousands. One hundred thousand more voters in these New England states would truly put us on the map in our various districts. Such should be our ambition.

The time would soon come, then, when our influence would spread beyond our numbers.

Anything would be possible for us. Like all other elements that make up the American population, we too would have in the political sphere qualified, upright, and well-supported representatives who would do more for our welfare than all other measures combined.

We must be, or not be. Let us demolish all of the old prejudices that have hurt us, educate young and old, and seek naturalization in great numbers. We are betraying nothing.

We need not be more American than Americans. We must simply be practical and reasonable citizens. That’s all that the Constitution under which we live requires.

F. X. Belleau, Lewiston, Maine, September 14, 1924

[1] The translation is mine (P. Lacroix). If Belleau’s letter was indeed written in September, I have yet to find an explanation for the long interval leading up to its publication.

[2] This is a reference to Georges-Etienne Cartier. Many other writers before Belleau credited Cartier with this phrase, but a contemporary source confirming that he in fact spoke those words is yet to be found.

[3] Belleau is alluding to Robert C. Dexter’s “Fifty-Fifty Americans,” published in August 1924, which assailed Franco-Americans’ supposed dual allegiance.

Leave a Reply