See Part I here.

As it still does, commercial prominence translated into political influence. In the spring of 1891, the Chalifoux family welcome William Eustis Russell, the Bay State’s young Democratic governor, then visiting Lowell for the first time since his election. Former Lowell mayors, prominent businessmen, and editor Benjamin Lenthier of Le National were present at the same social affair on Wilder Street. Russell would appoint Joseph Chalifoux to represent Massachusetts at a convention of American states held in Chicago and coinciding with the Columbian Exposition of 1893.

From the standpoint of public policy, Chalifoux believed that continued industrial growth required expansion into foreign markets, since domestic production far exceeded American demand. It may be that he had an expansionist approach in U.S. foreign policy. At a banquet of the Lowell Board of Trade, in 1893, one of his fellow speakers called for the annexation of Canada; those remarks seem to have come without controversy. But Chalifoux’s stance on monetary policy was much less popular within the Democratic Party, to which he belonged. He was a “silverite”; he supported the expansion of the money supply, which would raise prices while enabling Americans to pay back their debts more quickly.

The silverite cause divided and weakened the Democrats at the national level in the 1890s. It was also a thorny issue in Massachusetts. The party nominated Chalifoux as its candidate for the office of state auditor in 1897, but within days he formally withdrew from the race; it appears his monetary views were likely to cause embarrassment to the entire ticket. He accepted to seek the state treasurer’s office in 1900, 1901, and 1902, once the infighting had died down, however. All were losing races for Chalifoux.

His runs coincided with a period of GOP strength at the state level. Only two Democrats were elected to the governorship between 1884 and 1910, and between them they served a total of four years in office. Though a dedicated party member, Chalifoux seems to have accepted his losses—which may even have felt inevitable—with equanimity. In any event, there were silver linings. In 1900, though placing behind other candidates on the Democratic ticket, Chalifoux won more votes in Boston than his Republican opponent. Not bad for the little guy from Mascouche who could not count on the same family connections on U.S. soil.

At this point, we could easily believe that Chalifoux, entering the Anglo-dominated fields of business and politics, abandoned his cultural heritage over time or even turned his back on the Franco-American world. Like his contemporary Aram Pothier, his approach to public life could be read in several different ways. It remains that he maintained interest in the affairs of his fellow French-Canadian expatriates through his time in the United States.

In the 1870s, he served as an agent of Antoine Moussette’s L’Avenir national, a French-language newspaper founded in St. Albans, Vermont. He also attended a planning committee meeting ahead of the great Montreal convention of 1874. From 1898, we also find him leading the Chambre [d’affaires?] franco-américaine de la Nouvelle-Angleterre, which met in Lawrence; speaking at a meeting of the Société historique franco-américaine; and contributing to a monument that would honor Quebec poet Octave Crémazie. In 1909, he traveled to Trois-Rivières by car.

By no means did he turn his back on his French-Canadian roots. Neither was he a cultural separatist. His commercial and political activities are abundant proof of that. He also believed in careful integration by which his working-class compatriots would make the best of their lot. At the turn of the 1880s, he was instrumental in the establishment of a night school for immigrants with bilingual teachers. These classes would help provide newcomers—predominantly French-Canadian—with some of the tools that had enabled Chalifoux to succeed. In 1895, he led the local Union franco-américaine into a mock city election that would educate Francos about the American democratic system. The actual mayor was present; so was the local Oblate pastor. The event raised $1000 towards naturalization efforts.

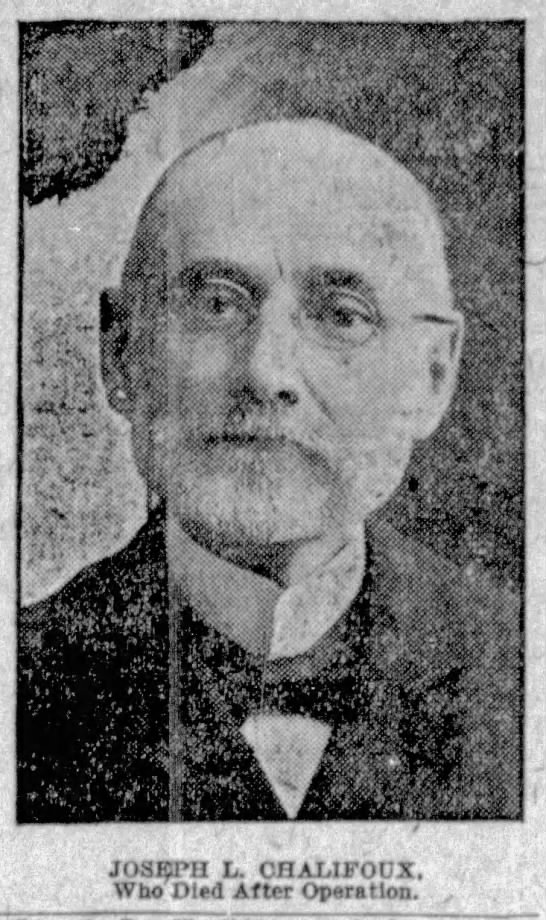

Chalifoux’s final years—he died in 1911—were marked by successive setbacks. He purchased the old Barristers’ Hall at the corner of Central and Merrimack streets in Lowell. In 1905, a large fire devastated that building. A new, elegant structure that still stands went up soon thereafter. Chalifoux may have hoped to move his store to this location; his son Harry carried that vision through in the 1910s. The Chalifoux department store in Lowell appears to have ended its operations at the end of the 1920s.

The Birmingham experiment ended unceremoniously. A fire of mysterious origins gutted that store in June 1907. Most everything was insured, but Chalifoux had seen this before and had no interest in rebuilding. Oliver decided to carry on, but within weeks tension between the brothers was boiling over. Joseph accused Oliver of siphoning money from store accounts, much of which was rightfully Joseph’s as the primary investor, for the purpose of establishing himself (Oliver, that is) in business. Joseph filed a suit against his brother to protect his assets, which now lay mostly in outstanding insurance claims. The partnership was dissolved.

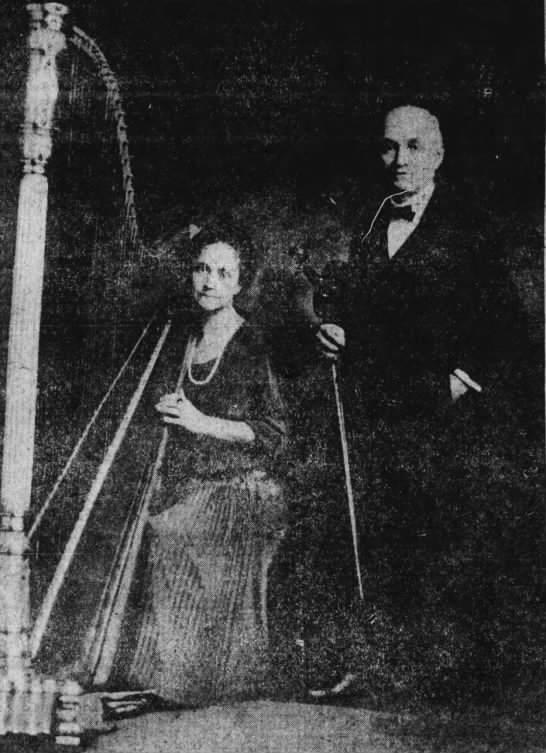

Oliver was back in business in his own name in the fall; yet another Chalifoux brother, Edward, came down from Lowell to help him out. By 1920, Oliver was listed as a merchant of musical instruments. Ten years later, he owned a music house. As the first store went down in smoke, Oliver and his wife Alice, who had married in Chicago in 1892, turned to their true passion. They offered performances as a violinist and a harpist, respectively, seemingly to wide acclaim.

* * *

It remains no small challenge to find the “real” Joseph Chalifoux—whether it be capturing his personality and public persona, or understanding how he leveraged opportunities into an enormous fortune. Victorian-era boilerplate biographies conceal a great deal. One would think that all prominent men of that era were respectable and esteemed—generic and boring. We then await a fuller portrait, which a more extensive survey of available sources would permit.

By virtue of his wealth, Joseph Chalifoux was not a typical French Canadian of his era. He nevertheless played an important role in his community, providing leadership and ethnic representation and molding fellow exiles’ collective action. More research will show what was possible for French Canadians on American soil, given the right experience and the right connections.

Sources

Several short biographies of Chalifoux appeared in print in his lifetime and at the time of his death. See, particularly, W. H. Goodfellow, Sr., ed., The Industrial Advantages of Lowell, Mass. and Environs (Lowell: W. H. Goodfellow, 1895); Boston Globe, October 2, 1897; Boston Globe, September 25, 1911; John William Leonard, ed., Who’s Who in Finance (New York City: Joseph & Sefton, 1911). Quebec newspapers noticed this Franco-American success story and reported on his cultural advocacy but also on his political views. See, for instance, L’Etendard, September 30, 1892, and La Presse, October 6, 1896. The Boston Globe paid close attention to the state races in which Chalifoux was a candidate at the turn of the twentieth century; the Birmingham News carried ads and reported on the drama of the summer of 1907. Further information about the Chalifoux family’s time in the United States was obtained from U.S. federal census returns and Quebec’s Drouin Collection via Ancestry.com. Readers seeking more information about Chalifoux and sources for this article are invited to use the contact form or the comment box below.

Leave a Reply