In prior years, this blog has looked at customs surrounding nineteenth-century holidays and shared a unique, French-Canadian take on A Christmas Carol. Following Prosper Bender and Honoré Beaugrand, our guide this year is again a prominent French-Canadian writer—one roughly of the same generation.

In Christmas in French Canada, Louis Fréchette penned short stories in English—without resorting to a translator—to open up North American French culture to people of British and Irish descent, and to cultivate their interest and sympathy. He added,

I have tried, in a few pen sketches, to convey some idea of the wild rigor of our winters, by putting, in turn, face to face with them, our valiant pioneers of the forest, our bold adventurers of the North-West, and our sturdy tamers of the floes, whose exploits of the past are gradually being forgotten in the presence of invading progress. I have endeavored to evoke some of the old legends, to bring back to life some picturesque types of yore, whose idiom, habits, costumes, and superstitious practices have long ago disappeared, or are disappearing rapidly.

In the meanwhile, I took pleasure in leading the reader to some of our country abodes, into the settler’s isolated cottage, into the well-to-do farmer’s residence, beyond the threshold of our villagers, inheritors of their forefathers’ cordial joviality. I have also invited the stranger into some of our city homes, initiating him into our family life, into our intimate joys and sorrows, and introducing him occasionally to some old and pious guardian of our dear national traditions. This I have done with no other concern than to strike the right key, to place the groups in their natural light, and to draw each portrait faithfully.

This collection of short stories revolves almost completely around the winter holidays. The book as a whole remains an enriching (if uneven) read; the extracts below are glimpses of lesser-known wintertime activities and traditions. The images are Frederick Simpson Coburn’s illustrations for the book.

The Breton Heritage

In the nineteenth century, it was a common claim that French Canadians were descended entirely from men and women of Brittany and Normandy. In “The Christmas Log,” Louis Fréchette explores the lore that would have been passed down from breton settlers—though there is ample reason to believe that this was a much later addition to French-Canadian folklore, if not Fréchette’s own addition. The story tells of an evil manorial lord’s attempt to cancel Christmas. In the process, the author parses out the roots of the Christmas log tradition:

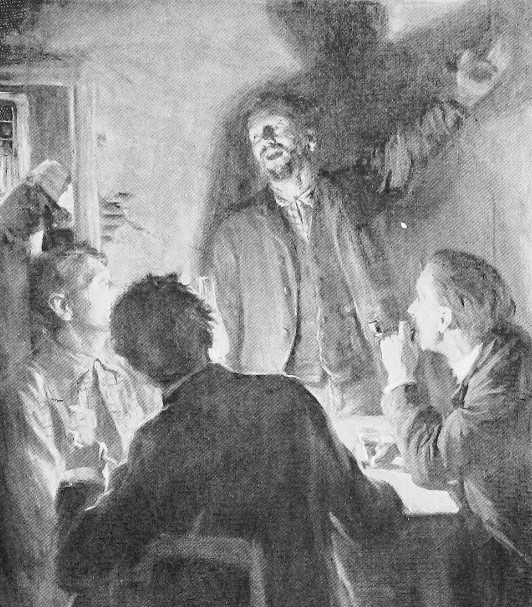

In Brittany—the valiant land of Brittany—in that good old fatherland of our forefathers, Christmas was not celebrated as it is here, where we simply attend midnight mass, and drink a glass of liquor, nibbling a branch of croquignole sprinkled with powdered sugar. There, it was the peasants’ day, the feast of the poor, and the country festival above all others.

The folk gathered in the châteaux and large farm houses; and there young and old waited for midnight mass with all manner of rejoicing.

First, they had what was called the ‘Christmas log,’ a huge fragment cut from the trunk of a tree, prepared and well dried beforehand, which was burnt in the great chimney place, after having been baptized by dropping over it a brimmer of wine from the last vintage; after which they sang the old carols, and feasted with cider and nieulles.

Nieulles, you know, were crusty little cakes baked for Christmas only. No Christmas was complete without them.

So they used to crunch nieulles; crunch [croque] nieulles, you understand. Evidently the origin of our croquignoles.

And they danced. Ah! well, our forefathers had not fine pianos as we have to-day. The violin itself was still unknown in the villages of Brittany. No waltzes, nor quadrilles, nor even cotillions. Boys and girls danced the bourrée and the carole to the sound of the biniou, an instrument something like the bagpipes you have seen with the Scotch regiments.

No floors brilliantly waxed, either, my children; nor Oriental carpets, nor elegant shining pumps. But people did not enjoy it the less for that, I fancy; at all events, it was not the harmonious clic-clac of the beechtree shoes on the resounding flagstones that could spoil the music.

Christ and Claus

Published at the end of the nineteenth century, Fréchette’s work attests to the increasing commercialization of Christmas. A story simply titled “Jeannette,” named for the character who slowly recovers from a childhood illness, highlights the ways in which religion and newer symbols cohabitated:

Crossing Before Quebec

“The Phantom Head” is a classic ghost tale that serves as a call to safety to those who would brave the ice of the St. Lawrence in wintertime. Fréchette takes the time to describe the challenge of crossing the mighty river in prior generations:

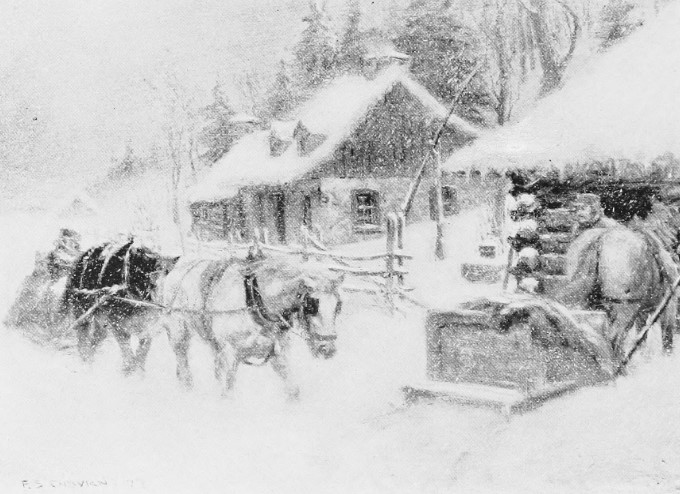

The traveller of to-day [ca. 1899] who crosses the St. Lawrence between Quebec and Levis, during the winter season, comfortably seated between decks in the powerful screw steamers which occupy only a few minutes in passing from shore to shore, forcing their way through the drifting floes, untroubled by mist or wind driven snow, can have but a faint idea of what this crossing, in old days, really meant.

“The trip was made in heavy canoes, or dug-outs, formed of two large trunks solidly joined by a wide and flat keel of polished oak, turned up at both ends, so that the craft could be used as a sledge when needed.

The captain sat astern, on a small platform where he commanded the manoeuvring, steering with a special paddle; while, at the bow, sometimes standing right on the pince—the slender projection of the prow—another fearless fellow explored the passes and watched the false openings.

In the front of the pilot, a certain space was reserved for the passengers lying on the flat bottom, wrapped up and covered with buffalo robes, perfectly protected from the cold, but with hardly the power of moving.

The rest of the canoe was crossed with thin planks, equally spaced, which not only strengthened the craft, but also served as seats for the men, who paddled in time, encouraging themselves with voice and gesture.

It was a hard calling; and, as the Canadian winters of those times were much more severe than those of ours, it was sometimes a dangerous one.

Every launching of the canoe—that is, every start from the shore—gave a thrill to the sturdiest. Down from the top of the batture—(the icy rampart built along the beach by the rising and falling of the tide, and the constant grinding and breaking of the drifting floes)—down from the top of the batture into the dark and swirling waters, the crew hurriedly jumping on board in a desperate entanglement of hands, legs and arms, it was a matter of a few seconds only, but every heart stood still until the flying start was accomplished.

And, Nage, camarades . . . Haut les coeurs! . . . Les bons petits coeurs!

A Deal with the Devil

Although a footnote, Fréchette’s commentary on the chasse-galerie—the most famous piece of canadien folklore—in “Tom Cariboo” deserves mention here.

The origin of this chasse-galerie legend can be traced to the [M]iddle [A]ges. In France and Germany, they had what was called the Black Huntsman. It was a fantastic coursing which rode in the air with wild clamour and desperate speed, through the darkness of the night. In French Canada, by a curious phenomena of mirage observed in some circumstance similar to that related by Fiddle Joe [the old-timey storyteller in this tale], a mounted canoe was seen flying through the air, and the same was naturally substituted for the Black Huntsman, who went also, in some Province of France, by the name of Chasse-galerie. It was supposed that the lumbermen—who, by the way, did not enjoy a very enviable reputation—managed through some devilish process, to travel in this way to save fatigue and shorten the distance.

There Be Wolves

The last short story is an old werewolf tale set in Saint-Antoine-de-Tilly, about 30 kilometers from Lévis. It follows Joachim Crête, who, without being an evil man in every sense of the word, failed to meet the most essential religious observances. Crête was a middle-aged bachelor who operated a grist mill with hired hand Hubert Sauvageau, a former log driver. Sauvageau seemed to encourage Crête’s every mauvais pli, taking advantage of his weaknesses and tempting him farther into the rut of dissolution.

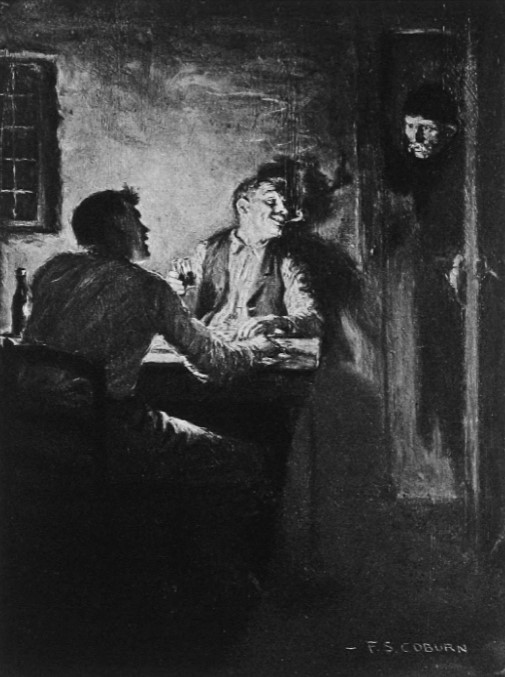

One Christmas Eve, Crête and Sauvageau were running the mill while drinking and playing checkers. Those who passed by pressed them to close the mill for the holiday and join them for midnight mass. The pair laughed off their neighbors’ insistent pleas.

As the men continued to play and the church bells stopped ringing, that night, suddenly the machinery jammed. The mill became deathly quiet. Crête and Sauvageau stared at one another. They slowly got up, closed the valves, inspected the gears and sluices, and found nothing amiss. Knowing the mill through and through, they were puzzled. They oiled the gears and reopened the works and the mill shuddered back into action. That was good enough for them. But as they returned to their game of checkers, sure enough, the gears froze again. And again, the two operators inspected the mechanisms. Yet this time there was no moving any part of it. “The Devil take the whole concern,” yelled out Joachim Crête; “let us go!”

As they were about to sit down, Crête heard a loud oath and everything went dark. Sauvageau, who had been carrying the lantern, must have tripped and dropped his light. Yet as Crête called for him there was no answer. When the door swung open, letting in the soft, grey light of the clear night sky, it wasn’t Sauvageau standing before his companion, but a giant growling dog. “Hubert!” Crête cried out to draw his friend from the darkness—but Sauvageau was to be neither seen nor heard. It dawned upon him that he was in the presence of a werewolf; likely the end of his earthly days had come.

The beast inched forward and, as the church bells rang again, the miller fell to his knees in repentance. Then, suddenly, the dog pounced and as Crête leaned back his left hand fell upon an iron hook, which he instantly raised up in a broad clawing motion. The hook fell into the head of the werewolf and everything went dark again.

Crête awoke the day after Christmas. The footsteps that brought him out of his slumber were Hubert’s. He could also hear the hum of the mill in the distance. Perhaps it had all been a dream. But as the room came into focus, so did Hubert’s face. It bore a long gash on its right side.

Saint-Antoine’s miller lost consciousness and died in the nearby lunatic asylum ten days later. With the thaw, three months later, the swollen river carried the mill away. Crête was forgotten and Sauvageau journeyed to another small town where he could be of service.

Source

Louis Fréchette, Christmas in French Canada (Toronto: George N. Morang and Co., 1899). Accessed on HathiTrust.

At the moment, this is expected to be the last post of 2021. Many thanks to all of you who’ve checked out my articles over the course of the year, with a special thumbs up to everyone who has shared or “liked” my work. While it is unclear what 2022 holds, I hope everyone will feel welcome to reach out and continue to engage on topics relating to Franco-American and French-Canadian history. Happy holidays!

Merci! As someone who did not have the luxury of growing up around my French-Canadian ancestors, this is great to read! Wishing you many blessings for the upcoming year!

Thank you Rebecca! Best wishes to you and yours!

Merci! When it’s – 30 in the Prairies, it’s good to have some new reading material.

Super! Thank you for reading!