Again has commenced and closed the annual migration of the French Canadians.—Daily have we seen them pass in companies, loaded with knapsacks and covered with the dust of travel; all dressed alike, with Canada gray trousers, homespun shirt, straw hat and moccasins. Every year just before haying, thousands of the French inhabitants of Canada come this side of the line to work during haying and harvesting. They come from all parts of Lower Canada, St. Cesaire, St. Hyacinth, fifty, sixty, even seventy miles, to work two months and return, carrying with them from twenty to sixty dollars as the result of their labors, more money than they would earn in a year at home. Most of them come on foot, but some drive over and sell their horses this side.

– Northern Inquirer [Bradford, Vt.], August 20, 1853

It is an attractive image: a small army of French-Canadian men marching as one, pouring over the border, and meeting the ancestral foe in the field. An inspired observer might see in these migrant Canadians “Normans overrunning and taking possession of another England,” as Prosper Bender would later put it. We may doubt whether this seasonal foray was in fact conquest of any kind. Yet, as we will see, the young, single men were not alone in turning to Vermont in the 1840s and 1850s. Family units began putting down roots. Before French Canadians could lend their hands to the northeastern textile industry, these families sustained Vermont agriculture, prevented the state’s population from declining, and created pathways to other areas of New England.

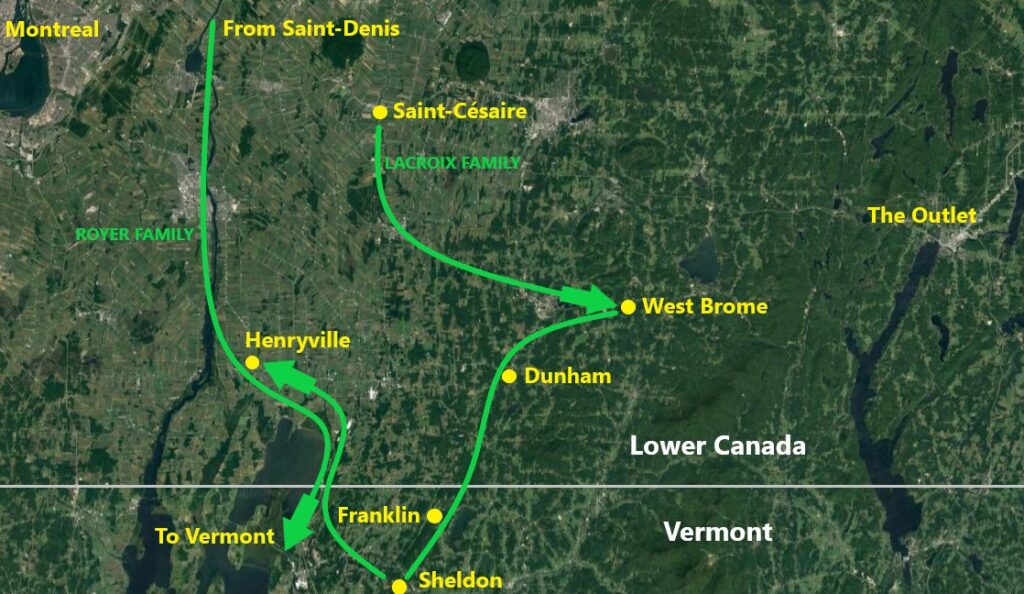

We know instinctively that this is a transnational story. It may be doubly so. In this era, French Canadians crossed cultural boundaries in different directions. They made their way into New York State and Vermont—and into the Eastern Townships of Lower Canada. The international boundary meant relatively little in all of this. The Canadiens and Canadiennes who went to the United States and to the Townships were impelled by similar forces and experienced similar circumstances. We might even say that they established Petits Canadas on Canadian soil, at least in areas that were still overwhelmingly English-speaking and Protestant. It is therefore not surprising to find individual families exploring opportunities on both sides of the border almost simultaneously.

If the written record is any indication, this story is generally better known of genealogists than of historians, no doubt due to the type of sources each group tends to scrutinize. The former have paid much closer attention to parish records, where, as we have previously seen, much of the story of early French-Canadian migration lies. Historians of Franco-America have focused to a far greater extent on the record of institution-building on the American side of the border—the pillars of survivance, which could only rise once relatively stable communities had cohered. (The extent to which institutions “make” an ethnic community will be discussed at a later date.)

The States

The Northern Inquirer correspondent quoted at the outset was not the first to comment on the annual movement of French-Canadian men. A full decade earlier, a traveler had come across just such a Canadien while exploring northern Vermont with a local farmer. He wrote of the conversation it sparked:

“These Canadian French,” said the farmer, “come swarming upon us in the summer when we are about to begin the hay harvest, and of late years they are more numerous than formerly.—Every farmer here, has his French laborer at this season, and some, two or three. They are hardy and capable of long and severe labor, but many of them do not understand a word of our language, and they are not so much to be relied upon as our own countrymen; they, therefore, receive, lower wages.”

The farmer stated that the workers typically received eight dollars per month, “the common rate.” Some men showed their knapsacks before leaving at the end of the season as proof of their honest conduct, but this specific farmer refused to inspect them.

A shower drove us to take shelter in a farm house by the road. The family spoke with great sympathy of John, a young French Canadian, “a gentlemanly young fellow,” they called him, who had been much in their family, and who had just come from the north, looking quite ill. He had been in their service every summer since he was a boy; at the approach of the warm weather, he annually made his appearance in rags, and in autumn he was dismissed, a sprucely dressed lad, for his home.

On Sunday, as I went to church, I saw companies of these young Frenchmen, in the shade of barns or passing along the road; fellows of small but active make, with thick locks and a lively physiognomy. The French have become so numerous in that region, that, for them and the Irish, a Roman Catholic church has been erected in Middlebury, which, you know, is not a very large village.

– Evening Post [New York City], July 24, 1843

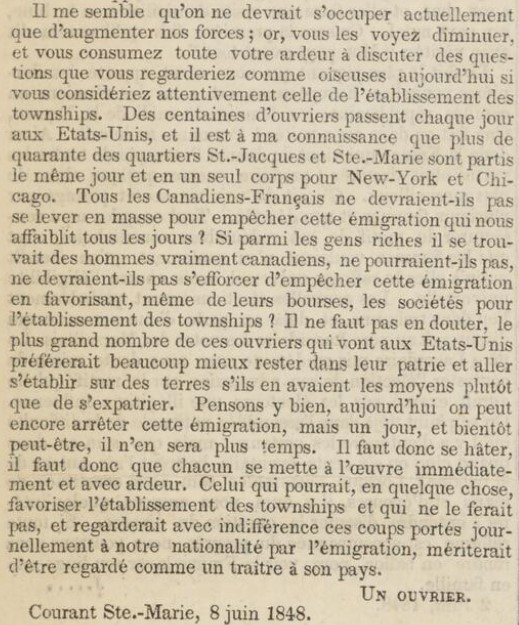

Lower Canada’s newspapers often discussed emigration at a fairly theoretical level. Still, some outlets gave concrete instances of migration. In early spring, 1850, it was reported that “58 young men from Sorel and its vicinity passed through the village of St. Hyacinthe (seven miles from St. Simon) on their way to the United States, where they hope to find employment for the summer (La Minerve, March 28, 1850, transl.).

Parish records complement these news stories. As abundant sacramental acts show, cross-border migrants were not exclusively meandering bachelors and young people eager to marry their cousins.

Dorothée Aubuchon bore two children—in 1829 and in 1831—in the United States before she and her husband Joseph Royer had them baptized in Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu. Joseph’s brother Pierre Royer and his wife also returned in 1831 after a foreign sojourn of at least two years. Another brother, Louis, is presumed to have emigrated and raised a family in the United States. Louis’s son Guillaume was in his twenties when he accepted baptism from a Catholic priest. Yet more members of this large extended family were living south of the border when they had children christened in Lower Canada in the 1840s.

They were not unusual. We need only take a cursory look at census records from Franklin County, Vermont, for a sense of the growing fields of migration. In 1840, Sheldon was home to Elim Gregwire, Joseph Perro, Joseph La Bon, and Louis Rye (our Louis Royer?) and their respective families—to name but a few French-Canadian households. In Highgate, we notably find Modor Tibado, Antwine Dusaw, J. B. Perriso, and Peter Riget (our Pierre Royer?). The Town of Franklin had at the very least 14 such households in 1840; they amounted to 8 percent of the local population. Due to the anglicization of names, the real figure was likely much higher. We could go on.

With regard to the Royer clan, many family units returned to Canada. But the fact that many spent years and years in Vermont tells us something of the nature of the migration even at the turn of the 1840s. Families could support themselves on U.S. soil; they could also find small communities of expatriates in rural regions. The well-established cross-border networks that brought young men to farms near and far also facilitated more permanent settlement.

The Townships

The story of French-Canadian settlement in northwestern Vermont—previously discussed here—is slowly becoming general knowledge among students of Franco-American history. Its connections to different areas of Quebec may be less so. Yet, just as the Eastern Townships proved to be the northernmost frontier of Vermont in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, as Jack Little argues, so the region became enmeshed in French Canadians’ fields of migration.

Semi-official syntheses of Townships history published by the Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture (1998, 1999) make an important point: in the second half of the 1840s, public figures reacted to rising emigration to the United States by proposing the Townships instead. Emigration and domestic colonization were inextricably linked. On the other hand, we see little of the early social and economic history of French Canadians in the region. When did they began arriving? Under what circumstances? Why did they choose one location over another? Did they plan to stay definitively? What cultural compromises did they make—and were these seen as sacrifices?

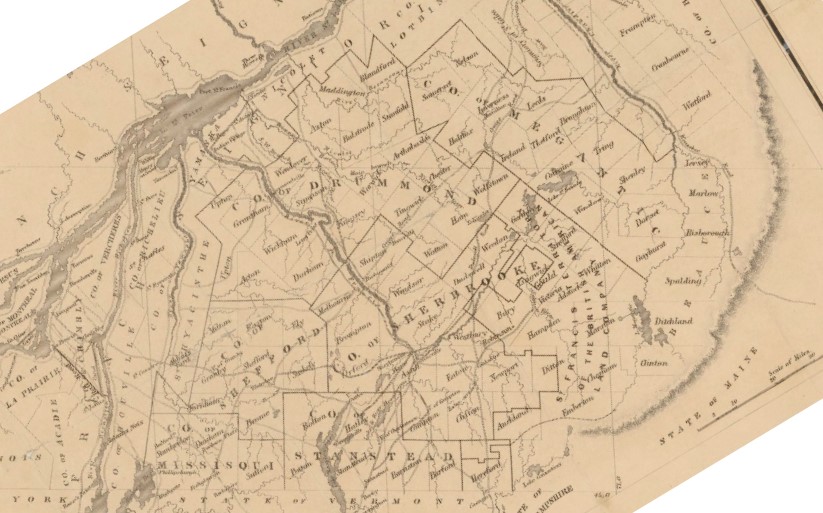

Across the span of the Townships, there were roughly three regions of French-Canadian penetration. The northern part, abutting the Beauce region, was essentially a hinterland of Quebec City. In the middle section, French Canadians expanded in a southeasterly direction on both sides of the Saint-François River. At last, families from the Richelieu and Yamaska basins moved towards the Piedmont region, which fronted the southernmost seigneuries.

Road construction reflected and reified this regional pattern—first with the Craig and Gosford roads, which stretched southward from Quebec City. In the second half of the 1840s, the colonial legislature invested heavily in east-west thoroughfares, particularly the Outlet Road that corresponds largely to the present Route 112. It connected Chambly to the “Outlet,” i.e. Magog, and from there to Stanstead. Improvements in roadways had an undeniable effect on French-Canadian migration into the Eastern Townships.

They were not the sole and only cause, however, for parish records tell of a little-known prehistory that requires further investigation. We might take, for instance, Antoine and Louise Bombardier, who married in Saint-Hyacinthe in 1814. At first glimpse, there was nothing unusual in their baptizing four children in Saint-Césaire from 1825 to 1831. Saint-Césaire was a growing parish fifteen miles above Saint-Hyacinthe on the Yamaska River. But the Bombardier family was already, in 1825, residing in Dunham Township—twenty miles, as the crow flies, above Saint-Césaire.

We should not imagine that Antoine Bombardier brought his family into a nearly-untouched wilderness. By 1831, one-third of Dunham’s arable lands had been cleared of forest. Still, this was a cultural frontier—the region was still dominated by Loyalists, Americans, and British immigrants—and it would require intense resourcefulness.

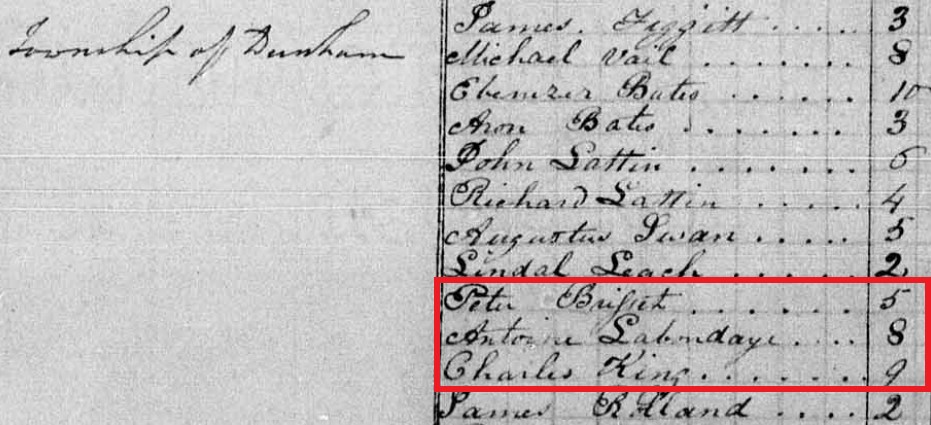

The Roy family (King in some records), which intermarried with the Bombardiers (or Labombardes), also arrived in Dunham well before the development of Catholic parishes or even a coherent missionary circuit. So did the Chrétien family. Maxime Chrétien and Angélique Durant were married in the Anglican parish of Dunham in 1838. The minister was the celebrated Charles C. Cotton. The couple took the Catholic sacrament of marriage two months later from a missionary priest. Maxime’s sister Nathalie married Antoine Archambault the following year; this too happened under Anglican auspices, though it seems that this couple never sought to receive the proper Catholic blessing (over the long term, the family did remain within the Catholic fold).

The Bombardiers were outliers with regard to their early settlement in the Townships. On the other hand, the Lacroix family, which needs no introduction to regular blog readers, was emblematic of a movement that has been too little scrutinized. In that sense, it mirrors the migration of Canadiens and Canadiennes to the United States also occurring in the early 1840s. Whereas his siblings nearly all went to Vermont in the 1840s, Edouard Lacroix settled in the Township of Brome. His father was also said to be in Brome at that time, but it seems this was the nineteenth-century version of dropping your kids off at college: he was helping Edouard get settled, for he himself was a cultivateur in Saint-Césaire.

The French-Canadian world of Brome that Edouard integrated was tiny. But it was there that he met the Royer family, the same we met above. Whereas the American adventure wasn’t quite over for some branches, others had found their way into the Townships, which, all told, may not have offered a particularly different experience. Descendants of Joseph Royer’s brother François Xavier were ascertained in Dunham and in Brome in 1841-1842. Joseph’s daughter Zoé married Edouard Lacroix in the winter of 1844; a Catholic missionary priest officiated. Cultural capital acquired in the United States could serve the extended family in the Eastern Townships.

The establishment of a parish in Stanbridge, west of Dunham, in 1846 helped focalize Catholic activity in the region—the entire transnational region, to be clear. On September 27 of that year, Father Leclair christened more than twenty children. Families came from all around. Two Benoit households made the trek from Enosburgh and Georgia, Vermont. Charles and Marie Laviolette of Berkshire, Vermont, had three children baptized, the oldest being four years old. Also present were Edouard and Zoé (Royer) Lacroix of Brome and the Royers of Dunham.

At the end of October, Father Leclair may have undertaken to cross the border, for the families that brought children resided exclusively in the United States. They came from St. Albans, Swanton, Highgate, Georgia, and Fairfax. Among them was a Royer—believed to be Pierre’s son—who came from Highgate.

One last case study. Like the Royers, the Létourneau family migrated to the United States at an early date. Ambroise and Marie Létourneau had their children baptized at various parishes along the Upper Richelieu River, near Lake Champlain, from 1829 to 1844. In each case, the Létourneaus were said to be living in Vermont. At one time they resided in St. Albans; later, they were in Sheldon. Like many French-Canadian families, they sought out the rites of the Catholic Church when they could. They nevertheless lived on a cultural threshold; it was likely in the United States that young Cyprien Létourneau learned to sign his name “Sylvester Turner.”

Perhaps finding that they could afford land more easily in Canada, all the more so with American cash in hand, the Létourneaus left Vermont and settled in the Townships, where their children married.

Legacies

These connections may all seem convoluted both in terms of geography and familial networks—and they are. But the point is not to memorize every single detail. Instead, we should retain the two main features of these processes.

First, although there were individual men engaging in seasonal work in the Lake Champlain region in the 1830s and 1840s, they were not alone. Families like the Royers and the Létourneaus were going to Vermont as units and spending years south of the border. They lived on a cultural frontier; at the same time, by no means were they isolated. They joined other French-Canadian families and they returned periodically to visit kin and to take part in the rites of the Church.

Second, the migration of families into northern Vermont and the Piedmont region of the Eastern Townships occurred simultaneously, with some kinship networks settling in both areas. It appears the border was at best an afterthought—an imaginary line that barely registered as they made life choices and sought to support themselves.

In 1860, a newspaper correspondent would claim that young people who had sought to build new lives in the Townships were discouraged from the lack of public assistance and from the poor quality of the land. Leaving the frontier “like hungry wolves,” they set their sights on upstate New York (Gazette de Sorel, January 17, 1860, transl.). There was some truth to this. However, the letter easily conceals the fluidity and back-and-forth nature of migration between the old seigneuries, the northern states, and the Townships. As always, in history, the overall picture is complex.

Moving forward a generation, in and around Brome, two children of Edouard and Zoé Lacroix married children of Antoine and Nathalie Archambault. Two daughters married Létourneau brothers. Three married grandchildren of Antoine and Louise Bombardier. We can only imagine the stories and cultural universe in which the next generation was raised, considering the challenges and experiences of all of these families across jurisdictions. It is not too much to think that the ripple effects were tangible. Of Edouard and Zoé’s twelve surviving children, all raised in Brome, five went to live in the United States, some in Vermont.

All of this may seem modest if not microscopic when compared to the French Canadians who tried their luck in Michigan, Illinois, Minnesota, and California. But in this critical phase we have an opportunity to better recognize the transnational connections that led to something bigger on both sides of the border.

A Note on Sources

Bender’s phrase comes from “The French Canadians in New England” published in New England Magazine (July 1892).

J. I. Little’s body of work is an escapable stop for anyone undertaking research on the Townships. See, especially, his Nationalism, Capitalism, and Colonization in Nineteenth-Century Quebec: The Upper St. Francis District (1989); Crofters and Habitants: Settler Society, Economy and Culture in a Quebec Township, 1848-1881 (1991); and Loyalties in Conflict: A Canadian Borderland in War and Rebellion, 1812-1840 (2008). He is also the author of important journal articles on the development of the region and a chapter in La francophonie nord-américaine (2013).

The IQRC books on the Townships are Histoire des Cantons de l’Est (1998) and Histoire du Piémont-des-Appalaches (1999). These works are key starting points for research on the topic and enable researchers to move past the most cited primary sources on the early Townships, to wit a manifesto and a novel.

See, on French-Canadian legacies in rural Vermont, my book review on the topic; on other stories hiding in parish records, see my piece on emigration to Franklin County, New York.

I have enjoyed your blogs; I have read many of them today. My family left Quebec through Ontario into Michigan, and some continued on into the western provinces and states. In Ontario some of the areas did not have regular priests and record keeping was not idea. 🙂 Also, I did do some onsite research in Ontario, and I was told that many Canadian French people left to the states because of the Amercian Civil War. Do you know anything about that? Based on what I read, it was always about the access of land and being able to have their life in the manor that they wanted to live. Another avenue to look at. Not one of my ancestors owned land in Ontario in the mid-1850’s that I could find. There were many British and Irish people that owned land in that time period. They bought land in MIchigan, so they had some kind of money. Thank you…

Hi Yvonne – thank you for commenting. In the early years of the Civil War, Canadians were more likely to repatriate, if they were in the States, than to immigrate. This was due to the economic disruptions of the war and perhaps also to the fear of facing conscription. In New England, textile mills recovered in 1863 and their labor needs changed the flow of population. But the war was a blip in a larger trend. Immigration had risen in the 1840s and 1850s and would continue once the war was over. Except in far northern Maine and northeastern Illinois, land ownership was relatively rare among French-Canadian immigrants in this period. Most worked for wages as factory operatives, loggers, farm laborers, etc.