Jean Baptiste

In the nineteenth century, Jean Baptiste became an unofficial moniker for French Canadians—a symbolic term applied to them by English speakers to mirror their own John Bull and Brother Jonathan. A glimpse of parish records in the St. John Valley suggests that there was something to it. But in the same records we also find one person who breaks the mold—a Jean Baptiste who by his very presence invites a more complex understanding of the Valley’s past.

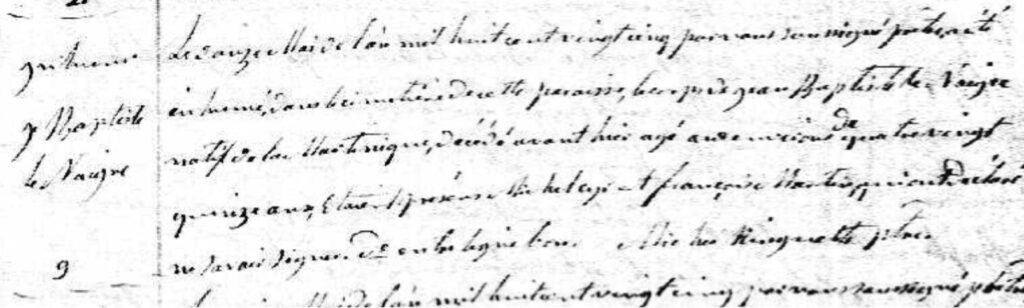

In the spring of 1825, the body of a lately-deceased 95-year-old man was carried to its final repose in the Saint-Basile parish cemetery. The burial record identified the man as Jean Baptiste Le Naigre. Le Naigre is not a surname or a “dit” name springing from either the St. Lawrence River valley or Acadia. From the record, its origin is plain: Jean Baptiste was a native of Martinique and somewhere between his place of origin and his final place of residence, perhaps even only in the latter, people had known him by the color of his skin.

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century burial records often exaggerate a person’s age at death. Even if this Jean Baptiste died at the “mere” age of 80, it is almost certain that he would have been born into slavery. He likely spent his young years toiling on a sugar or coffee plantation. He may have been taken to Montreal while France still controlled the St. Lawrence; he may have found his way to a British ship—and then to British North America—during the wars of the late nineteenth century.[1] The greater mystery of his coming to the Madawaska territory may remain forever unsolvable; his death preceded the Deane and Kavanagh report (1831) that could have offered clues. But here, along the St. John River, were French speakers, here was peace, and here was relative safety from the violent world of Western enslavement.

Two men were identified as witnesses at Jean Baptiste’s funeral: Michel Cyr, husband of Madeleine Thibodeau, and François Martin, husband of Scholastique Levasseur. Both had come to the Valley as youths and were now pillars of the community. When Deane and Kavanagh ambled through the region in 1831, the Cyr and Martin families were living near one another on the north bank of the St. John River, near the mouth of the Madawaska. Cyr seems in retrospect a likely employer for Jean Baptiste. He owned 100 acres and hardly anyone on the north bank of the river had cleared more land. He may have needed extra hands, hired hands, to manage the farm.

Five years after Jean Baptiste’s passing, we find another person of color in the Madawaska settlement. At the western end of the Valley, in or near present-day Fort Kent, lived a Black man between the ages of 35 and 55. The only other person in his household was the man whose name appeared in the census: Isaac Yarrington, who was about the same age. Yarrington, a native of either New Jersey or New York, left traces of his time in the Valley: he married Catherine Nadeau, he passed away in 1862, and his body was laid to rest in Saint-François. His companion, perhaps a hired hand, remains unknown to us, or at least unnamed. He had left the region by 1840 and perhaps even by the summer of 1831.

If the St. John Valley was any kind of melting pot prior to 1840, it was a crucible of two francophone cultures in which a few handfuls of Irish, Scottish, and American settlers were sprinkled. Still, the presence of two Black men—and likely more—raises questions about their experiences and about the history of cross-cultural encounters writ large in this overwhelmingly French-heritage region.

Political Agitation

A few French Canadians—the Ayottes, for instance—joined the initial wave of Acadian settlement on the Upper St. John River in the 1780s. Most Canadiens who came did so gradually through the nineteenth century. In this respect, Joseph Pelletier might be considered a pioneer. He married Madeleine Leclerc in Kamouraska in 1804. The following summer, they baptized their first child in Saint-Basile. The family established itself in the Valley, where many children remained and had descendants of their own. Joseph and Madeleine, on the other hand, left in their later years, perhaps after deeding their land to a son. In January 1840, they were living in Rivière-du-Loup. Their life would seem very conventional if not for a document signed before notary Alexis Beaulieu in 1840 that tells of Joseph Pelletier’s politics. It reads in part:

Before the notaries public for the Province of Lower Canada, undersigned, came and appeared Mr. Joseph Pelletier, formerly a farmer, living at Rivière-du-Loup in the county of Rimouski, formerly of the parish of St. Luce of Madawaska, who by these presents has made and appointed as his general and special representative the person of Mr. Savage, farmer living in the parish of St. François of Madawaska, to whom he grants the power, for himself and in his name, to request and receive in whatever form may be, and from all people authorized to this end, the compensation that may be awarded to him by the American government, to have jointly with many other people of the said parish of St. Luce of Madawaska elected a candidate or member at the said place of Madawaska to represent them in the Chamber of Congress of the said place of America approximately nine years ago, and of receipts give all valid release and discharge, promising to have the entirety agreeable, and ratify should there be a need.

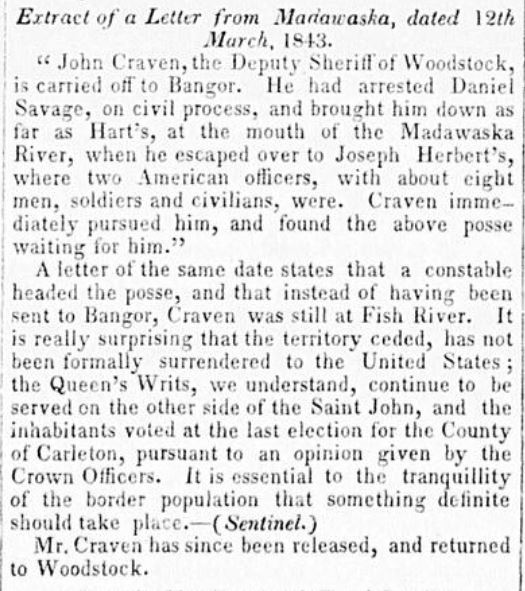

The record takes us back to the summer of 1831. Within weeks of Maine commissioners Deane and Kavanagh’s journey through the Madawaska territory, an emboldened John Baker took action. Baker had previously founded a “Republic of Madawaska” west of present-day Edmundston and Madawaska. He hoped to gain the attention and support of authorities in Augusta, essentially forcing them to formally assert control over the entire region on behalf of the United States. He was imprisoned in Fredericton for what the government of colonial New Brunswick deemed to be sedition. By 1831, again on his lands, Baker was ready for a new volley. He organized a meeting at the home of Pierre Lizotte and there they elected a town moderator, a clerk, and a representative to the state legislature (not Congress, it seems, as Pelletier later claimed). Apparently, Americans in attendance far outnumbered the French-heritage settlers—but we can be sure that Pelletier, who lived near the Bakers, was among the latter.

Also among the attendees was American Daniel Savage, the Mr. Savage of Pelletier’s notarized claim. Savage built the first mill on the Fish River and, though less flamboyant than Baker, shared his Americanizing agenda.

Baker’s latest efforts provoked. They gained attention. But the outcome was as before. In the fall, a Maine paper reported that Baker’s friends and supporters—Savage, Barnabas Hunnewell, and Jesse Wheelock—were facing justice in New Brunswick. They were found guilty of attempting to establish foreign authority on British soil and “seducing [the French inhabitants] from their natural allegiances,” the French being “natural born British subjects.” Each was to pay £50 and serve three months in jail.

Britain had a fair claim to the region. Its colonial government had granted lands to those British subjects on both sides of the St. John River in the 1780s. It also dispatched magistrates and troops more easily, hence Baker’s recurrent run-ins. But this did not make the Upper St. John Valley any less of a disputed area. Even in 1840, when Joseph Pelletier recorded his claim, uncertainty reigned. In recent years, British and American forces had built blockhouses and sought to back diplomatic maneuvers with acts of sovereignty on the ground. The hopes of Baker and others were dashed in 1842, when the Webster-Ashburton agreement established the border as we know it today.

It is still unclear what kind of reward, exactly, Pelletier thought he would receive for his part in the 1831 proceedings. Well, it would be a moot point and not merely because of the terms of the Webster-Ashburton agreement. Joseph died in the spring of 1840.

Widowed, Madeleine returned to the parish of Frenchville to live with a child.

Cold, Hard Cash

The Anglo-American struggle for control of the greater Madawaska territory had much to do with the area’s vast timber reserves—foremost among which, stands of giant white pine.

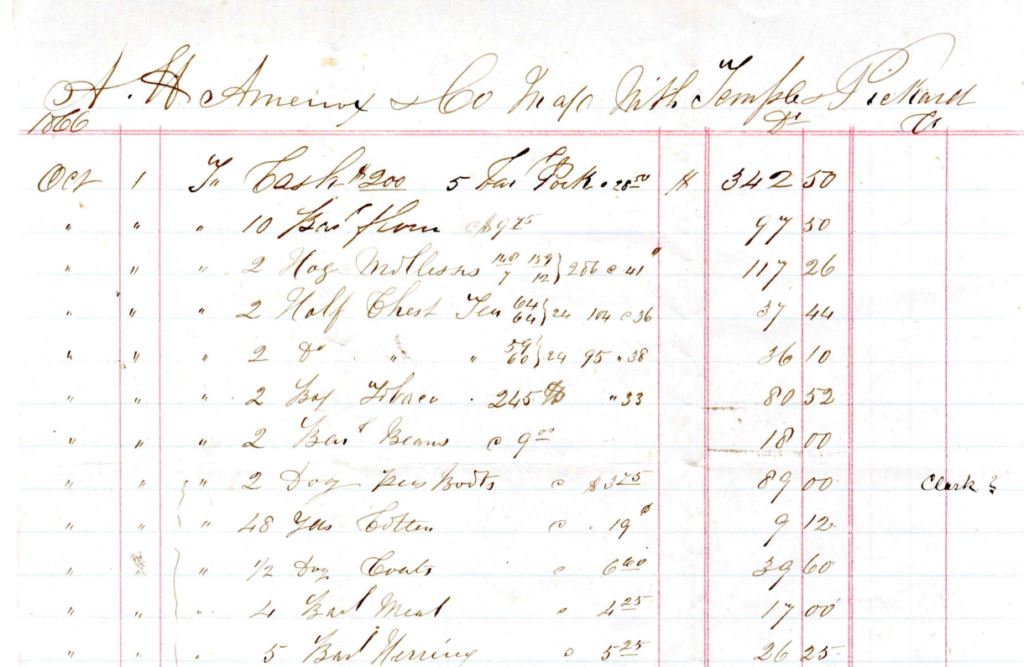

There was more to timber than geopolitics and large-scale economic forces, however. Lumber merchants revolutionized life in the St. John Valley. They were responsible for the first major influx of outside capital to the region. They had money with which to pay lumberjacks and yarding crews—though we should not discount the prevalence of a credit system through local stores operated often by the same merchants or contractors. Buttressed by financial connections to markets along the Atlantic, the same well-placed people had the resources to feed, equip, and support workers.

Thus arose an agroforestry system where, previously, farmers had exploited and managed lumber reserves on their lands. Any commercialization occurred locally. Residents could and did live from agriculture. Small luxuries—a few essentials, too—could be purchased on the ledger system in the few Valley stores. But, from the 1830s onward, there was another option. Young men could spend five months in the woods and thereby help support the family farm and slowly collect the means of founding a household of their own. This newfound opportunity was tangled in the challenges of economic development, including uneven power relations and dependence on the whims of capitalist market forces.

According to some newspaper reports, there were other drawbacks, the agricultural foundation of the St. John Valley itself being threatened.

In March 1855, a Portland paper reported on the “[g]reat distress . . . on account of the scarcity of provisions” that prevailed in far northern Maine. The situation was such that the state legislature appropriated $6,000 to supply residents and assist them in their battle against smallpox.

Bad harvests were nothing new—but the reason given for the incipient famine was. According to the same article,

The cause of this destitution is said to be the employment of a large portion of those settlers who cultivate farms in the farming season, upon the river in driving logs, till too late in the spring to sow and plant their fields as usual. Consequently a large number of the farms in that settlement yielded no crops last season.

Could it be that the press, misunderstanding the realities of the Madawaska territory, took liberties and offered its own original and dubious explanation? It wouldn’t have been the first nor the last time. What’s more, during the summer of 1854, the St. Lawrence valley had been affected by intense heat and dry conditions that burned hay as it grew and sparked wildfires. In some areas, animals had to be slaughtered prematurely with the understanding that there wouldn’t be enough forage to feed them at the end of the winter. The farms on either side of the St. John River likely experienced the same conditions.

Still: there was likely some kernel of truth, however small, in the article. That is borne out by a similar piece, this one published in Fredericton and reproduced in Kamouraska, almost exactly twenty years later. Again, a “great distress” had befallen the Valley. It read:

Agriculture has been shamefully neglected for ten years [in Madawaska], and to it shingle manufacturing has been substituted. The consequence is that shingle wood has become scarce and the price of shingles is quite low; poverty is the common state of a large number of families. Seed grain is lamentably scarce, and in general people have no money to purchase any, even if seed were abundant. The last several years have not proven very favorable to the harvest, which is to be attributed as much to the bad management of past years as to bad weather.

This brings us closer to the kernel of truth. Northern Maine and northwestern New Brunswick had suffered from a short growing season and maladapted crops from the beginning of agricultural settlement. Families could meet their needs in good years. Too much or too little rain, late frosts in the spring or early frosts in the fall, the wheat midge or potato rot—any of it could bring the region to the brink of famine, such that more than once it had to rely on the charitable graces of governments.

In the decades after Webster-Ashburton, the influx of lumber capital and small-scale industrialization complicated the matter. It seems some people were now taking chances by seeking a living from wage labor either year-round or for as long as they could. Work in lumber-related trades may have been relatively alluring to young men. But this, like many other factors, would have upset the region’s ongoing and delicate reliance on subsistence agriculture to meet its dietary needs.

The opportunities of capital were also its costs.

Sources

The record of Jean Baptiste Le Naigre’s burial appears in Acadia, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1757-1946 on Ancestry.com. Census data was also drawn from Ancestry.com. The Deane and Kavanagh report appears in the Collections of the New Brunswick Historical Society, vol. 9 (1914), 344-484; excerpts appear on The Upper St. John River Valley. Joseph Pelletier’s notarized claim is available on the BAnQ website. Roger Paradis’s “John Baker and the Republic of Madawaska,” also available online, provides valuable context, as does Wiggins’ History of Aroostook. The November 1, 1831 issue of the Eastern Argus carried the story of the Americans facing justice in New Brunswick. The reports of distress and neglected agriculture appeared in the Eastern Argus, March 14, 1855, and the Gazette des campagnes, May 28, 1875. See, on the harvests of 1854, L’Ere nouvelle [Trois-Rivières], September 2, 1854, and Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, September 22, 1854. The works of Béatrice Craig provide valuable context on forestry and the early market economy of the St. John Valley. Primary sources covering commerce and financial transactions may be accessed in the Acadian Archives’ digitized Gerry Morin Collection.

For more on the St. John Valley:

- Those Other Franco-Americans: The Madawaska Mirage?

- Hauntingly Silent: Some Questions Concerning Maine’s English Education Bill

- Othering the Madawaska in Travel Narratives

- The Unique Story of Public Education in Northern Maine

- A Complete 180? Webster-Ashburton in Hindsight

- Lesson Plan: Maine Acadians

Readers may also be interested in my recent “Making Acadianness in Northern Maine” (Part I and Part II).

[1] Massachusetts, which at that time included Maine, abolished slavery in the early 1780s. The long journey towards emancipation in the British colonies began in the 1790s.

Fascinating! I love seeing how real people are affected by events, environment, personal choices.

And then I look for the personal connection to gauge whether there might be some unknown-to-me influence of a place and time personally.

Joseph and Madeleine are “somehow-cousins” when I look at their lines.

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree