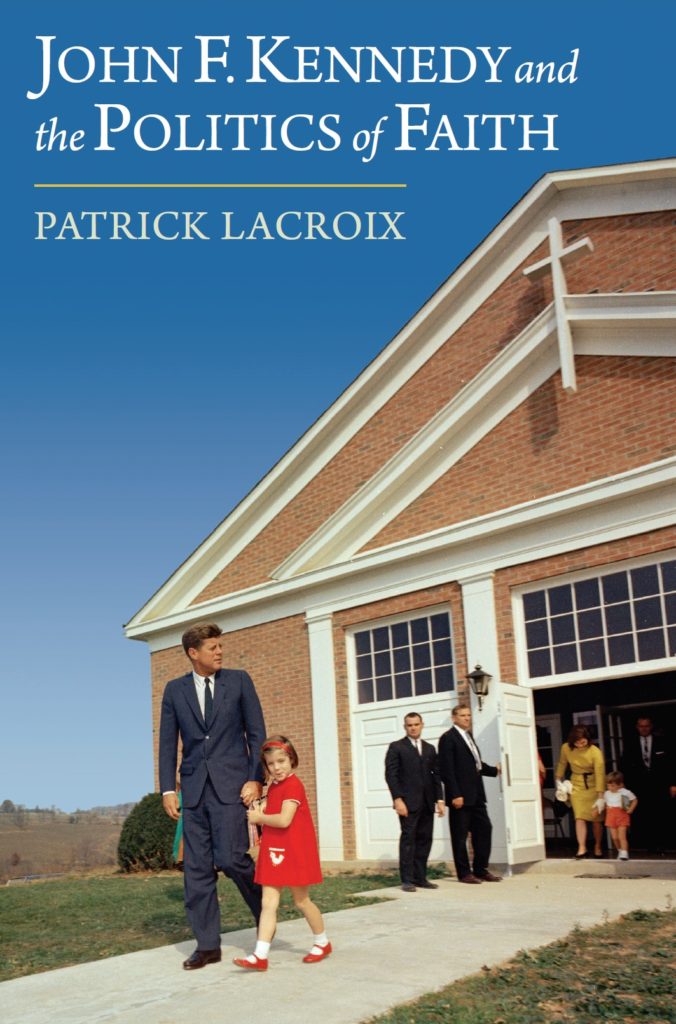

As many of you know, my first academic book, John F. Kennedy and the Politics of Faith, is now available from the University Press of Kansas. I am touched by the expressions of interest and support I’ve received in the last few weeks. As readers might suspect, the book is drawing attention due to its timeliness—and that stems from forces far beyond my control. A reevaluation of the Kennedy years was in order when I embarked on this project, six and a half years ago. The irruption of a certain Republican presidential candidate onto the national stage changed the landscape of politics and political history. With his departure from Washington and the inauguration of a second Catholic president, Kennedy’s time in office has much more to tell us than I could have suspected at the outset.

Many of you also know that my research interests are not confined to wealthy, womanizing presidents from the Northeast. Well before I settled on a dissertation topic, at the University of New Hampshire, I was researching the history of the French-Canadian diaspora. In the last nine years, I have sought to push the bounds of the field—on this blog, at conferences and on podcasts, on other virtual platforms, and in academic publications. I’m fast approaching ten peer-reviewed journal articles on Franco-American history writ large, including its Quebec backdrop. I have never been at a loss for projects, for unexplored sources and topics in this field abound. (I made this case in greater depth in the inaugural post of the French-Canadian Legacy Podcast’s blog.)

That brings me to my second book project. I am pleased to announce that my manuscript, tentatively titled “Tout nous serait possible”: Une histoire politique des Franco-Américains, has been picked up and is now under contract with the Presses de l’Université Laval. It will be supported by the Chaire pour le développement de la recherche sur la culture d’expression française en Amérique du Nord, which boasts a long record of influential publications. CEFAN chair holder Martin Pâquet is a distinguished scholar of immigration whose research experience extends to Franco-Americans.

Here again I am pushing the boundaries of academic and general knowledge in Franco-American history. In my series on “Those Other Franco-Americans” and some of my published work, I have argued that we need to learn more about people who lived outside of the “Crown Jewels” of Franco-America (Woonsocket, Fall River, Lowell, Manchester, and Lewiston), those who lived beyond the shadows of the proverbial “Steeples and Smokestacks.” New York State lies in a strange purgatory when it comes to the Franco story. We need to delve more deeply into pre-1860 migrations. We also need to do justice to women’s experiences, better address the process of acculturation, and study those who did not work in textile mills—including the commercial middle class. My manuscript on Franco-Americans’ political history is no more than a small step in the search for a more holistic representation of their complex journeys on American soil.

In fact, it is meant to build on and enrich existing literature. The thrust of my work has never been to say that the work that has come before mine is wrong. But there is a difference between a historian and a storyteller. A historian is an inquirer driven to explore what we think we know of the past and what we don’t know, ceaselessly endeavoring to refine our understanding of bygone times. Every foray is incomplete. If undertaken in a spirit of intellectual honesty, however, every foray is worthwhile.

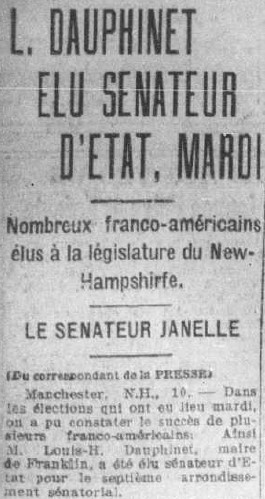

I hope my book will be greeted in that very spirit, for there is much we do not know about the meeting of French-Canadian culture and American values and institutions. That is especially true in the sphere of political action. Drawing evidence from all seven northeastern states, my book challenges the notion that Quebec immigrants and their Franco-American descendants were indifferent to U.S. politics or inconsequential at election time. It also clarifies Franco voters’ partisan allegiances, which changed from one generation to the next and varied from place to place. Concerned about “ethnic recognition,” Franco-Americans also paid attention to more substantive issues; increasingly, they voted as a socioeconomic class, reflecting an important stage in the process of American acculturation.

The book (re-)introduces important figures who are now largely forgotten: the fiercely partisan Ben Lenthier; Henri Burque Highway’s namesake; the leader of a grassroots political rebellion in Berlin and the father of the New Year’s Day holiday in Massachusetts; Harold Dubord, who came within a few thousand votes of becoming Maine’s first Franco senator; the Catholic priest and son of a textile mill worker who became mayor of Plattsburgh; and many others.

Though it stretches to some 350 pages, my manuscript is by no means comprehensive. Thousand-page volumes are unpublishable, but that’s what it would take to truly cover, from a regional standpoint, those seventy years of Franco-American politics—to say nothing of the subsequent seventy years. In other words: there is still so much we can do to deepen our understanding of this political issue and I would invite all researchers, whatever their background or academic credentials, to help enrich this subfield.

Written in French and published in Canada, this book will, I hope, inspire Quebeckers to take interest again in their estranged, mostly English-speaking cousins south of the border. Too often, Franco-Americans have served as a cautionary tale in the public discourse of la belle province. They are held up as fallen French Canadians—even people who betrayed la patrie. I would contrast this to Quebec media outlets’ genuine expression of pride when noting the political accomplishments of their Franco brethren in the first half of the twentieth century. Though I harbor no grand illusions, perhaps this book can help expand opportunities for mutual recognition and understanding among people long separated not only by a border, but prejudice and misconceptions as well.

Publication is currently scheduled for September 2021.

Congratulations, that is great news. Any chance this will be translated into Anglais?

Thanks so much Dan! It is too soon to tell, but some glimpses of the book’s main characters do appear on this blog. I am also planning to give book talks in English – virtual and, if we’re lucky, in person. Stay tuned!

Yes…the strange purgatory of New York!!! Why the empire state was different than New England for Franco Americans?? I can’t wait for an explanation that is better than what’s been proposed – none of which is academic. Then again some say there wasn’t much difference at all. No wonder historians shy away from the strange purgatory.

I’m glad you and many others are seeking to change that conversation and bringing more attention to New York’s Franco-Americans. But with all the books and articles on Francos with “New England” in the title, it’s a narrative that is hard to shake. Meanwhile, U.S. historians too often associate immigration into the state with New York City and those coming from overseas. Those coming in the other direction are overshadowed. From Clinton County to Cohoes and beyond, I’m hoping to help change that in at least some small way.

J’ai hâte de lire ton nouveau livre. Garde-moi au courant. Merci.

Merci beaucoup Ron! J’ai bien hâte de vous visiter dans le Rhode Island!