Although there is ample room for concern about the state of Franco-American culture in the U.S. Northeast, we can take (some) solace in the sustained pace of research on—and the level of interest in—Franco-American history. New works have shown that we need not envy the research endeavors of the 1980s and 1990s that led to landmark studies still in use today. Such recent publications are perhaps more impressive for the fact that they arise from a much less favorable academic and cultural climate.

In the last five or six years, we have witnessed the publication of—among others—David Vermette’s A Distinct Alien Race, my work of political history, historically-informed texts in French All Around Us, and several memoirs and biographies. Such veterans of Franco-American historical writing as Yves Frenette and Mark Paul Richard are as prolific as ever and a younger generation of researchers are following in their footsteps. Crucially, new projects and publications are feeding upon one another—a sign of a genuine historiographical conversation and a living and breathing field. People on the field’s periphery are taking note. Laura Demsey’s Indiana University thesis on linguistic shifts among New England francophones, completed in 2022, is a good example. This is not a work of history per se, but it does distill available historical information by way of an introduction. The context offered by Demsey exposes the sources that early-career scholars are accessing. Her thesis draws from standards like Armand Chartier’s synthesis, but also works published in the prior five years by Leslie Choquette, Robert Forrant, and Robert Perreault.

Here I offer a list—by no means comprehensive—of works that have added to that impressive body of research in the last year. These are significant articles and books that also speak to the vitality of the field and deserve our attention.

Rhea Côté Robbins, “Where Are the Franco-American Women in the State of Maine?” Maine History (2023)

If we have long lamented the relative invisibility of Franco-American history, the relative invisibility of women within the Franco-American narrative should be doubly concerning. In this article, Côté Robbins identifies the historic challenges—prejudice in various forms and the power of homogenizing identities—to the assertion of women’s experiences. Scholars can redress that injustice by seeing through the dominant tropes of Franco-American women as mothers and mill workers. To highlight the variety of experiences yet to be fully represented, the author includes short biographical notes for more than thirty women who made a lasting mark on their communities. She insists, further, on the importance of personal testimonials, gleaned in ethical research, and work that addresses the “knowledge vacuum” among people of French-Canadian and Acadian descent.

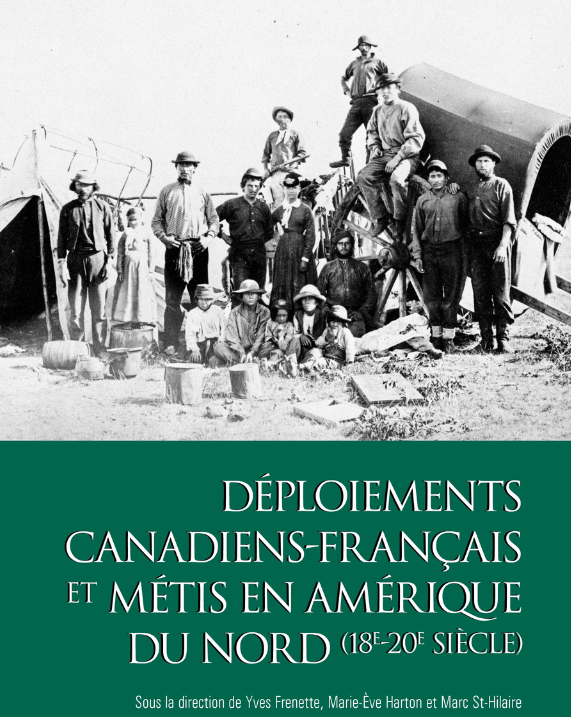

Yves Frenette, Marie-Ève Harton, and Marc St-Hilaire, ed., Déploiements canadiens-français et métis en Amérique du Nord (18e-20e siècle) (2023)

It is no small task to represent, in so few words, a work that includes eleven substantive chapters on disparate aspects of French-Canadian migration. Those studies cover, as the title suggests, nearly two centuries of history, as well as migration fields spanning the continent—from Washington State to New England via the Canadian Prairies, Minnesota, and Quebec.

Most contributing authors utilized population databases to better understand patterns of settlement. This is a methodologically rich book. Danielle Gauvreau’s chapter quantifies the French-Canadian population in Quebec that had previously lived in the United States in the early twentieth century. This type of work can help guide new research on the cultural and economic effects of repatriation on a societal scale. Historian John Willis draws attention to a woman who, though atypical in many ways, highlights the sheer mobility and versatility of her national group. Aurise Gill lived on the Prairies before migrating to New England; a dressmaker, she lived in Lynn and Boston.

Still in the Northeast, co-editor Marie-Eve Harton and Léon Robichaud explore Canadian residential patterns in Manchester, New Hampshire. In 1910, two-thirds of French Canadians in the city lived outside of the Little Canada. In these other urban areas, occupations were more diverse. Cohabitation with non-nuclear relatives declined the longer a family unit stayed in the United States. Although some families remained in Little Canadas for generations, life in these ethnic neighborhoods may have been transitory for many more people. Beyond these small gems, it is also worth highlighting the value of bringing different regions of study in a single volume, in hopes that research on New England and on more westerly states might be mutually enriching. (See, for a longer description of Déploiements, my review on HistoireEngagée.ca.)

Jacob Albert and Susan Pinette, “Franco-American Newspapers and Periodicals in the Northeast: An Inventory,” Québec Studies (2023)

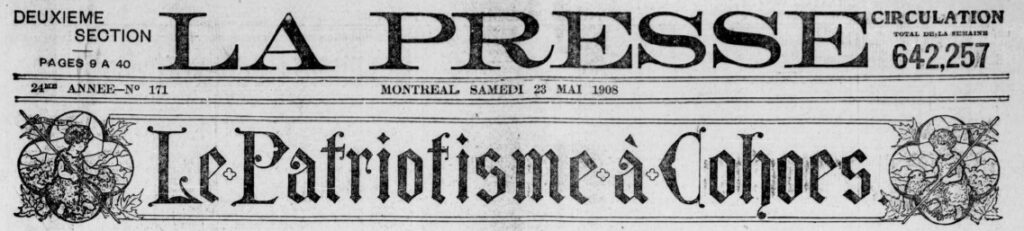

Not quite a traditional research article, this study introduces an indexing project that holds great promise from the standpoint of historical research. The authors highlight the challenge of accessing original sources written by French-Canadian and Acadian expatriates and their descendants due to lack of funding, cultural devalorization, geographical breadth, etc. In light of these obstacles, Franco-American-focused institutions joined forces to inventory known French-language periodicals on the Franco American Digital Archives/Portail franco-américain. A work in progress, as new information comes to light through archival repositories and the public, the online index aims to address the neglect of Franco-American periodical sources in research. In fact, much of the Franco story remains sealed in newspapers that have lain untouched for generations. Albert and Pinette’s article includes an eleven-page appendix listing French periodicals known to have existed in the United States.

Mark Paul Richard, Catholics across Borders: Canadian Immigrants in the North Country, Plattsburgh, New York, 1850-1950 (2024)

Faithful followers of Query the Past read about Richard’s latest work in a recent blog post. Catholics across Borders is a deep dive into a community that does not perfectly fit our common understanding of Franco-American life. Plattsburgh was not dominated by gargantuan textile or pulp and paper mills. Its proportion of French-Canadian residents was much higher than in many other locales. These Canadians arrived earlier and developed generally more cordial relations with residents of other backgrounds. Richard highlights aspects of community life that have often escaped other scholars’ glance, not least blackface performances. Yet, it is the depth of research in religious archives that truly stands out—much of which tell of the contribution of women religious to the development of Plattsburgh’s cultural institutions. Richard shows the promise of such archives in the study of other communities across the Northeast.

By sheer coincidence, Richard’s book appeared in print on the same day as my article in New York History. My study sacrifices local depth to establish the general terrain of French-Canadian settlement across the state and offer quantitative estimates for different areas. Despite the availability of census records, this is an imperfect science; enumerators were not expected to distinguish English and French Canadians until the end of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, there is a sound case to be made that New York was, of all states, numerically the largest destination for French Canadians by the time of the U.S. Civil War. That startling fact—and the persistence of Franco-American communities well into the twentieth century—should invite further research on this and other neglected regions. (Let’s note, in passing, that of the periodicals indexed by Albert and Pinette, 33 were published in New York State.)

Maxwell Pingeon, “Nationalizing American Catholicism: Irish Power, French Canadians, and the New England Language Wars, 1853-1936,” University of Virginia (2024)

Pingeon sheds new light on seemingly familiar issues in this recently-defended dissertation. It is best not to reveal too much at this juncture; we can save the extensive commentary (and fanfare) for the publication of the resulting book. Suffice it to say that Pingeon places the religious battles stretching from the Flint Affair to the Sentinelle controversy in a wider context and on a scale heretofore unattempted. Research at the Vatican archives speaks to the significance of this project. Ultimately, Pingeon takes Franco-Americans’ cultural battles as a case study in larger dynamics, particularly the construction of nationality and a specifically American Catholic Church—with conclusions that might hold equally for Poles, Germans, and other white Catholic immigrant groups.

* * *

Undoubtedly, for the foreseeable future, a small number of keywords—Little Canadas; the Catholic Church and textile factories; discrimination and assimilation—will continue to serve as linchpins of the Franco-American historical narrative. There is something to all of that. At the same time, we can broaden that vision, enrich historical narratives with nuance, and portray past lives in their full unguarded messiness. Through quantitative data, through unexplored newspapers, through religious archives, through conceptual shifts, new research is helping us do that.

Some aspects of Franco-American history clearly call for more attention. Although scholars conventionally place the grande saignée between 1840 and 1930, proportionally little work has been undertaken on social and economic conditions, community building, or the intellectual climate prior to 1865. Studies of the post-1945 period are for the most part cursory. What’s more, Franco-American history has traditionally been written from a strictly ethnic perspective—meaning that researchers have not always paid attention to developments outside of the ethnic community. Increasingly, they are looking laterally or placing Franco-Americans in a larger context and thus engaging in comparative work. In the 1970s and 1980s, a new generation of academics integrated the insights of the new labor history. Now, we are catching up to debates in gender studies, race studies, and other fields.

The next major contributions will come from a special issue of Recherches sociographiques edited by Yves Frenette and Danielle Gauvreau; it will mark sixty years since the publication of a similar issue. At that time, texts by Albert Faucher, Gilles Paquet, and Léon Bouvier had offered a fresh look on the French-Canadian diaspora. Beyond this journal, as noted, we can expect much more from of the abovenamed researchers and many young people who are coming up through the ranks.

The real challenge, then, may not be the richness or strength of research in this field, but accessibility. Books published by academic presses are often expensive; journals are often paywalled. Just as this blog came into existence to bring research to a wider public, so we should invite other scholars to look beyond the academic silo. Podcasts, public lectures, op-eds, and museum exhibits are already contributing to the dissemination of highly specialized research; we may hope the trend continues.

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - May 11, 2024 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

Is there any published work (or sources of material), other than the local church records, on the French who settled in Franklin County, New York, especially in Constable or Malone? I and some of my distant kins, are researching John Baptiste Landry (parents unknown, but several children christened at St. Regis Reserve before 1830), who is listed on the 1840, 1850 Censuses for Constable, NY., then he disappears, but descendants live in Franklin County, NY & Springfield, Massachusetts.

Hi Wanda. Unfortunately there are few printed works on the French-Canadian history of Franklin County. You may want to check with the Northern New York American-Canadian Genealogical Society in Dannemora and the Franklin County Historical & Museum Society in Malone.

Jean Baptiste Landry appears in my post on Franklin County:

https://querythepast.com/franklin-county-new-york/

As the post suggests, part of the family’s story may lie in parish and missionary records north of the border. The Drouin Collection on Ancestry.com holds the baptisms, marriages, and burials performed by Fr. Moore.