Like thousands of other families, economic and demographic pressures carried them away from the ancestral heart of French Canada and into the breadbasket of the Richelieu and Yamaska rivers, into the “foreign” Eastern Townships, and into the fields and factories of the Great Republic. The descendants of Jean Lacroix and Marie Anne Fradet—both of them born in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War and old enough to remember the invasion of 1775-1776—would embody the challenges of rural life in nineteenth-century Quebec. They illustrate, en miniature, the expansion of French Canadians within and across political boundaries.

From the arrival of the first Lacroix in Canada, around 1670, most descendants had lived in the Bellechasse region, facing l’Ile d’Orléans just below Quebec City. By the end of the eighteenth century, the region’s parishes were among the oldest in the colony. The area was, by rural standards, densely populated and heads of households could wonder how and where they would settle their sons when they reached adulthood. Perhaps it was that kind of scouting mission that brought Jean Lacroix’s father to Saint-Denis on the Richelieu River in 1787—a trip we only know about because he died and was quickly buried there.

Marie Anne, Jean’s wife, gave birth to their first six children in Saint-Charles, Bellechasse region, in the 1780s and 1790s. Perhaps in the spring of 1801 or 1802, the whole family moved 200 kilometers to the south and west. Their new home was near the little hamlet of Saint-Hyacinthe on the Yamaska River. There, Catholic parish registers had opened about a generation prior. This region, too, was growing quickly; it at least promised more opportunities and access to a broader agricultural hinterland.

The family seems to have lived a relatively settled life in or around Saint-Hyacinthe. Most of the Lacroix-Fradet children who lived to adulthood married there or in neighboring parishes. Whether they lived comfortably or on the economic margins, we do not yet know. But, as Jean remarried twice in the 1830s, when his children had reached adulthood and some level of independence, we may suspect that he personally had the means, in his seventies, to support himself and a new partner.

It is easier to read between the lines of available records with the next generation. Jean Jr. married the widow Marie Mainville, a mother of one, at La Présentation, between the Yamaska and Richelieu rivers, in 1815. Together they would have nine more children and for twenty years they would lead a somewhat uncertain and itinerant life.

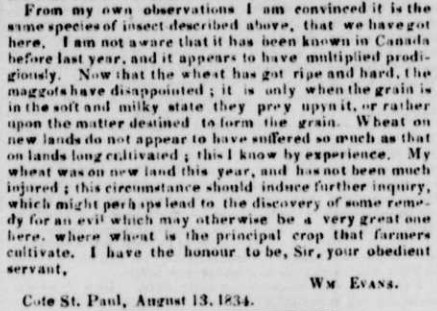

Their circumstances were not unusual. From 1815 to the turn of the 1840s—roughly the span of a generation—the population of Lower Canada doubled. Demographic pressure limited access to the means that would enable people coming of age to form their own households. Intergenerational wealth disparities grew quickly. As historian Allan Greer argues, established households generally fared well, but young men had to go farther and farther afield to find wage work or land; family formation was delayed when it was at all possible. In the same decades, Lower Canadian agriculture underwent a profound transformation. Quebec historians have long debated the primary cause of that transformation (many have called it a crisis) and it won’t be resolved in this post. Some facts are undeniable, however: expansion into less fertile areas of the St. Lawrence River valley; the arrival of pests like the wheat midge, which decimated crops; and the decline of wheat, to be replaced by hardier crops like barley, potatoes, and peas, whose commercial value was negligible.

Opportunities outside of agriculture were few. The fur trade was in rapid decline. The lumber industry, though thriving in the 1820s and 1830s, increasingly faced competition from abroad and would be crippled by changing trade policies in the 1840s. Immigrants rushed into the limited opportunities for wage work in urban centers. In short, there is no wondering why Jean Lacroix (Jr.) and Marie Mainville were so often on the move for twenty years.

The family lived close to kin, in the vicinity of Saint-Hyacinthe, until about 1824. We then find them farther north at Saint-François-du-Lac, near the mouth of the Saint-François River. The last three children were baptized in the 1830s in Saint-Hyacinthe, Saint-Damase, and Saint-Césaire—successive parishes on the Yamaska as one navigated upstream, suggesting that year by year the Lacroix clan was seeking new opportunities farther along the river. As late as 1834, when Jean was about forty-five, he was recorded as a day laborer, by no means an enviable position. The next year, however, we find him in parish records as a cultivateur (a settled farmer) in Saint-Césaire. There he and his wife would remain for the next twenty years, the remainder of his days.

There was little to Saint-Césaire aside from the chapel. The Montreal Gazette carried a report from the area in 1833; a traveler had been quite impressed with the progress and promise of the hamlet. The correspondent added,

A branch of the Yamaska river, which traverses the townships of Granby and Farnham, is crossed at a toll bridge erected at the village of St. Cesaire, the church of which is small, neat, and amply sufficient to supply the wants of what may be regarded as ‘the back settlements.’ The river is said to be twenty-five feet deep here, and is navigable for river craft of about sixty or seventy tons, from St. Hyacinthe as far as this village; and even beyond for vessels of smaller burthen.

Historian Christian Dessureault has, retrospectively, offered a much less sanguine view. The seigneurie of Saint-Hyacinthe, straddling the Yamaska, was then experiencing natural growth and a negative migratory balance. In other words, the population was growing quickly and people were leaving. This pattern was present in each of its five localities except in Saint-Césaire, the edge of francophone settlement in the region. Between 1825 and 1831, this was the only place in the seigneurie growing through migration. It also happened to be exceptional by its poverty, at least in comparison to the surrounding parishes. In new settlements, plots were smaller and economic competition more acute. In this lay a glimpse of Jean and Marie’s adult lives—chronic instability until the mid-1830s, when they put down roots in one of the poorest areas of the Yamaska valley.

Jean and Marie Lacroix’s oldest children had little to inherit and were likely to experience the same kind of life cycle. And so they dispersed. The eldest, Louise, married in Saint-Césaire; she and her husband would move to Stukely in the Eastern Townships in the 1850s. Her brother Edouard—my ancestor—moved to the Townships as a youth of twenty and remained there until his death at the end of the century. (More on him in the next blog post.) The youngest sibling, Antoine Lacroix, lived in Saint-Césaire and almost without a doubt inherited the parents’ hard-earned plot.

We have yet to find marriage records Jean and Marie’s eldest sons, Jean Baptiste and Joseph, but marry they most certainly did. Their spouses, Marie Anne and Domithilde Lavallée, appear to have been sisters. Briefly, in the 1840s, both of these young households were living in the parish of Sainte-Victoire-de-Sorel, east of the Richelieu. By 1850, they were in Vermont. (That may be where the record of their weddings is to be found, if they crossed the border several times.) Félix Lavallée appears in the Sainte-Victoire records in 1849 as a day laborer in the United States; it may be through their in-laws that Jean Baptiste and Joseph Lacroix opted to look south.

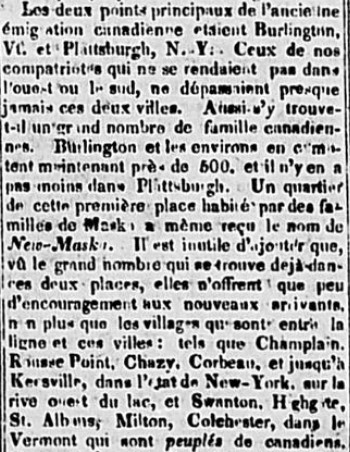

These families settled in rural Franklin County, abutting Lake Champlain at the northwestern corner of the state. The Champlain–Richelieu waterway was then a well-developed commercial axis and a growing migration corridor. Although it is fashionable to begin the story of Franco-America in the era of the Civil War, people in the southern part of Lower Canada were already moving to Vermont and New York in large numbers in the 1840s. A neighborhood of Burlington was even nicknamed “New Maska,” in those years, for the number of migrants who had come from the lower Yamaska River.

As Lacroix became Cross and Lavallée became Lovely, one could easily believe that these families were immersed in an English-speaking environment that ensured rapid and inevitable assimilation. Not so fast. Even in those early years, Vermont’s northwestern quadrant had an immense French-Canadian population. In 1850, in Franklin County as in Burlington, one out of every seven residents was Canadian-born; that is not counting children born on U.S. soil to one or two Canadian parents and who grew up as French-speaking Catholics. These people were constantly in touch with the “homeland” and lived among exiled compatriots. Jean Baptiste and Joseph lived near one another and they were joined by their sister Lucie. She had married Edouard Mercure in 1849. They lived most of their adult lives in Fairfax, Vermont; we find them in census records as Lucy and Edward Marcher and both would live into the twentieth century.

Jean Baptiste, Joseph, and Lucie Lacroix and their partners likely made out better in the United States than they would have in Canada, had they stayed. Gradually, farm labor enabled them to steady themselves economically and provide for their respective children. The story is slightly different for the other sons of Jean Lacroix and Marie Mainville, François and Michel. On November 13, 1846, Francis and Michael Cross, both natives of “Masco” (Maska) in Lower Canada, enlisted in the U.S. Army at Whitehall, New York. Military records help paint the picture. Francis had blue eyes and light blond hair; Michael—later he appears as Mitchell—had grey eyes with slightly darker hair. Both were 5’7” and had a sallow complexion.

Though we might want to characterize these men as adventurous, and no doubt they were to an extent, their decision to enroll must have come from a place of financial desperation. Their prospects were likely lower than their parents’ had been at their age. The brothers served in the Mexican War and earned their military pay, but only one would come back. Francis died in Texas after the end of hostilities. Cholera was the probable cause.

Mitchell raised a family in the Eastern Townships of Quebec but appears to have crossed the border again and again. He was living in the hamlet of Beaver (probably just a small cluster of farmhouses) outside of Fairfax, Vermont, when the federal government awarded him a military pension in 1887. He died in Sweetsburg, Quebec, in 1901. Present at his burial were his nephews Pierre Alphonse Larocque and Orin Lacroix, both of whom already had their own cross-border connections.

In all, of Jean and Marie Lacroix’s nine children, who were born from 1816 to 1835, five earned their bread on U.S. soil. They were already living the grande saignée.

It would be easy to overestimate the significance of border crossings in that era. For one thing, the French-Canadian oikumene, the area of the St. Lawrence River valley occupied by people of French descent, had been expanding gradually and steadily in almost every direction since the beginning of European settlement. Higher population growth accelerated the process. It was perhaps only a matter of time before that area of settlement spilled onto U.S. soil, as it did in the middle part of the nineteenth century.

From a purely economic standpoint, a move to Vermont was not much different from an earlier migration from Bellechasse to Saint-Hyacinthe; it was driven by the same factors. Cultural conditions were different, but French Canadians migrated with their faith, language, and customs and, whenever possible, transplanted their institutions. As they moved, their cultural capital expanded and their bilingual children were provided with new opportunities. Yankee Vermonters were then moving west by the thousands, opening up space for migrant workers who might in time buy land. It was people like these Lacroix laborers who kept the state’s population from dropping in the second half of the century.

Next week: A French-Canadian Journey: Saint-Césaire to St. Albans

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - July 24, 2021 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

Hi,

Came across this site as I was working on my family tree.

I am curious to know if you have any knowledge on the LaCroix’s tied to Penetanguishene, Tiny, Midland areas.

My search has taken me that direction.

Regards,

Chris

Dear Chris: Thanks for reading and reaching out. No, unfortunately I haven’t found connections to those areas, but maybe we’ll find we have a common ancestor. Happy research!

Hi,

Working backwards from Lafontaine area I believe the migration is Drummond Island and/or Wayne County, Michigan.

As I check census, marriage, baptism & death records-everything keeps bringing me back through those regions.

Riveting! As is my habit I keep looking for family intersections. Our ancestors were at the vey least circling each other in St. Hyacinthe.

I also have a lot of Côté ancestors and relatives floating in Saint-Hyacinthe in the same years, in case those connect with your tree.

Hello Patrick –

My name is Donald LaCross (Lacroix). I have been doing research on my Lacroix Roots since the late 1960’s, and through some source of luck, found your article about Lacroix and St. Albans last evening.. I had never viewed it before and I found it fascinating! My Ancestor was Felix Lacroix (Cross, Lacross) who was born in St. Albans Bay in 1849. His father was Jean-Baptiste Lacroix (1818) and his mother was Marie-Anne Lavallée (1817). Felix and his spouse (Adéline-Marie Lanouette (1854-St. Ours Quebec) were married in Bakersfield Vermont in 1870 (I have a copy of the original Marriage Certificate). It has been especially difficult to locate a lot of information about Felix, but I have managed to fill many pages of notes and records.

I began my search long before the Internet was available, and have found it to be a Godsend. So much easier than going to Montpelier, Burlington, St. Albans, and the border community churches in Quebec for vital records. Your article has filled in many gaps that existed in my genealogy of the Lacroix family. I wanted you to know how much it has been appreciated. It was difficult to find many records that existed for Jean Baptiste in the U.S., although my most recent was a Probate Record in Underhill Vermont, where Felix is listed as the son of Jean-Baptiste. (I knew that, but had been unable to locate the death date of Jean-Baptiste until I found that small Probate Record.). There is however, no other documentation of his death that I was able to locate.

My reason for writing you is to express my thanks for the articles you researched about Lacroix in Vermnt, particularly in St. Albans (where I reside).

Thank you so much for your interesting reads of the Lacroix Family and St. Albans, Vermont. It is sincerely appreciated!