See Part I here.

Themes

In my edition of Jean Rivard, the editor establishes the influence of Don Quixote and Robinson Crusoe on Gérin-Lajoie’s novel. But the parallels that struck me first and foremost—parallels that will be familiar to American readers—involve Walden and Horatio Alger novels.

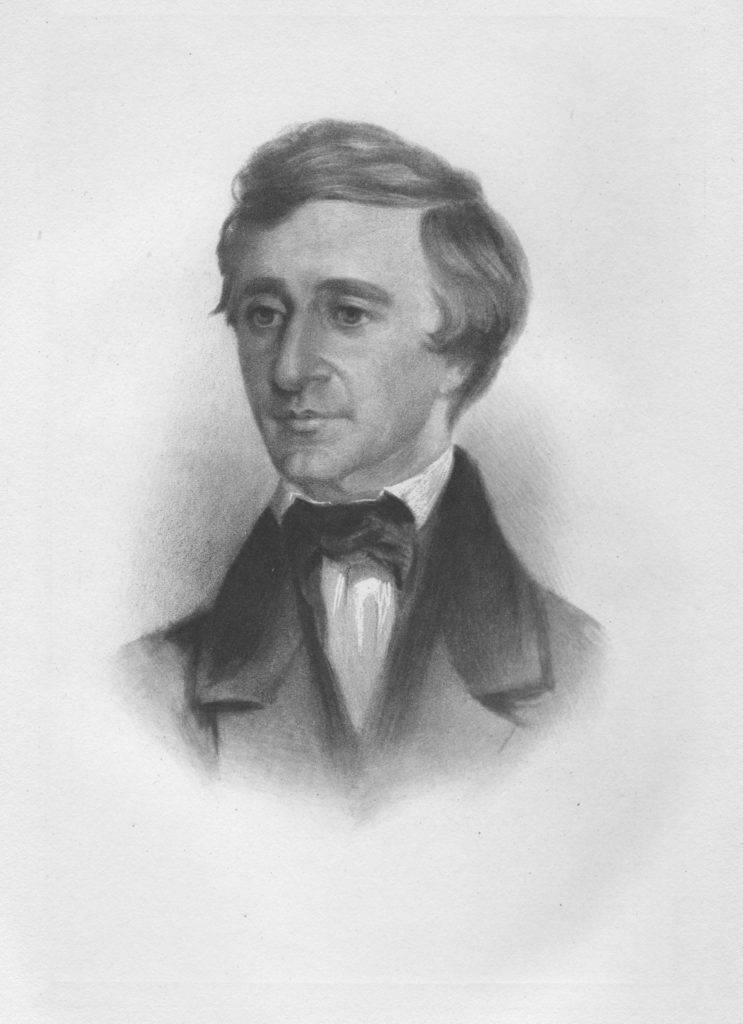

Both Henry David Thoreau and Rivard go into the woods to live deliberately. Their projects are material (each keeps meticulous records of their expenses and income) and spiritual (one transcendentalist, the other conventionally Catholic). While Rivard’s approach to nature is far more utilitarian—it’s a development ethos—both are consciously rejecting urban life as dangerous morally and otherwise. Was this Gérin-Lajoie’s French-Canadian answer to Thoreau? Montreal book shops did carry Walden as early as 1854, the year of its publication. Thoreau’s death in the spring of 1862 occurred just as Jean Rivard was beginning to appear and may have inspired Gérin-Lajoie to revisit the Bay Stater’s writings. Either way, as some scholars have argued (Robert Major, for instance), Canadian writing was by no means insulated from the flourishing American literature of the 1840s and 1850s.

The premise of the typical Horatio Alger narrative (which postdates Rivard) is simple: if you’re an honest, hard-working family man (yes, it’s gendered), you will succeed. You may face struggles, but you are bound to prevail. Again, Chapter XVII of Rivard exemplifies this perspective:

Let’s pause for a moment before the marvelous power of work. What have we seen? A young man admittedly graced with the greatest qualities of heart, body, and mind, but lacking in all other ways—alone, practically abandoned in this world, unable on his own to provide for himself or for anyone else… We have seen him banging his head in hopes that one good idea would come out, when God spoke to him…

Rivard, the author goes on to say, turned wilderness into riches simply through force of will, hard work, and the spirit of self-reliance. And yes, he is also a family man. The trope, again, is quite American.

Of course, these cultural and literary connections should not diminish the essential fact that Gérin-Lajoie was addressing French Canadians and offering a distinctly Canadian agenda. That agenda was political, but not necessarily as we might expect.

Although the story takes place in the 1840s, we find no reference to the Patriotes who had risen up against British colonial power only a few years earlier. In the first tome of Rivard, that British power is in fact wholly invisible—and we might conclude that it is irrelevant. With Gérin-Lajoie, we see clearly the spirit of the Rebellions being displaced by a whole new kind of activism and patriotism.

In Chapter XIII, we discover that Rivard is fulfilling “a sacred duty to his country, his family, and to himself.” In our main character’s voice, the author writes, “The man who doesn’t work, supposing even that he is wealthy enough to be independent, as we’d say, deprives his country of the wealth that his labor would bring, and though he might call himself a patriot, I wouldn’t believe it. One who does nothing to increase the general welfare is no patriot.”

Here is the influence of the 1850s—an era of energy, of rapid technological and economic advance, of competition among nations, all carried by a sense of new possibilities. To work fruitfully as Rivard does is a divine injunction, but its blessings are not relegated to the afterlife.

That is, there’s work to be done. Let’s cast aside our petty squabbles and grand political theories alike, Gérin-Lajoie seems to be writing, and focus on the practical measures that will quickly contribute to the prosperity of Canada. That program is even more explicit in the sequel. In Chapter VII of Jean Rivard, économiste, titled “The March of Progress,” the author describes the spirit of development carried by the construction of grist and lumber mills. “After the ringing of the church bells,” we learn, “no music could be more pleasing to the poor settlers’ ears than this sound of saws and milling, or that of the cascade providing hydraulic power.”

We might think that this economic progress—this patriotic pursuit of the general welfare—is dependent simply on hard work. Quite nearly it is. But Gérin-Lajoie isn’t letting the government off of the hook. In Chapter XX of the first book, he castigates the political class for a half-century of failures that had led to mass emigration.[1] Under Lord Elgin’s “administration,” finally, public authorities had turned their attention to the development of unproductive lands. (This is slightly anachronistic; Elgin had yet to appear on the horizon when Rivard was clearing his plot.)

Gérin-Lajoie follows the recommendations of a legislative report issued in the late 1840s and cites the observations of Catholic missionaries in the Eastern Townships. Prosperity and progress will come from domestic colonization—expansion into the undeveloped regions of Lower Canada, including parts of the Eastern Townships. That much is clear. But young men will be deterred from becoming pioneers, and expansion will stall, until and unless good roads are built.

As we consider the political aspect of the author’s program, it’s not much of a misinterpretation to think that better roads into the wilderness will be Lower Canada’s salvation—roads will unleash Canada’s productive energies.

Legacies

We’ve seen that it is a priest who counsels our young man to go east, into the wilds of the Townships. We’ve seen that the musical hum of the sawmill is surpassed only by the ringing of church bells. It is a pastoral injunction that ends the first book; in the next, as a parish is founded in Rivardville (Chapter IV), we find our hero and the newly-appointed priest symbolizing “the temporal and spiritual powers supporting one another and working hand in hand.”[2]

We thus see economic progress that is compatible with Catholic obligations. We cannot help but connect the two books’ religious themes with the likes of the curé Antoine Labelle and the ultramontane Jules-Paul Tardivel. But it is important to note that Jean Rivard contributed to the ideological climate that makes Labelle and Tardivel (or at least their visions) possible. From 1862, Rivard was held up as what might yet be—the standard, the ideal, the achievable utopia. It fed into a providentialism, not the transnational providentialism that would lead to reconciliation with Franco-Americans, but a vision that favored the development of Quebec as an agrarian French-Canadian homeland.

The novels’ legacy was also literary. Admittedly, Rivard was almost alone in its genre for forty years. It found a strong response in the next decade in Honoré Beaugrand’s Jeanne la Fileuse, which also offers an extended view of life in rural Quebec. Beaugrand also insisted on the failures of public policy—the failures of political leadership. But his work was in many ways a call to compassion for those who had left the province, something different from the clerical appropriation of Rivard that assailed all those who lacked the fortitude to become défricheurs.

The littérature du terroir reached maturity in the 1930s, shortly before new artistic winds and social realities displaced it entirely. Works like Trente Arpents, Le Survenant, and Marie-Didace were far less romantic: they discussed intergenerational conflict, friction between neighbors, financial ruin, illness, laziness, and so forth. Still, they were nostalgic and, like Rivard, written by folks who needed not worry about late frosts.

Works in this genre have their artistic merits and, certainly, they should be read for the glimpses of rural realism they offer. But more significant yet is the intellectual and political climate to which they contributed and whose effects were felt until recently.

[1] This is the most explicit reference to emigration to the United States in Jean Rivard, le défricheur; there are also a few passing references to those who would seek their bread in a foreign land. In Chapter XII of the sequel, Charmenil mentions their old college mates who have go to the United States; one works in a New York inn, another has gone to California. The fictional letter also mentions that one friend had gone to join “the army of Mexico,” one of the few contemporary references to those Canadians who had fought in the Mexican-American War of the 1840s.

[2] Although it is not explicitly religious, the heavy emphasis on temperance may come as a surprise to many readers, the temperance campaign having been far more marginal in Quebec than in Anglo-Canada and the United States.

Leave a Reply