In her first memoir, former Vermont governor Madeleine Kunin discussed her experience as a young reporter in Winooski, a predominantly French and working-class city abutting Burlington. Mayor Armand Rathe was then at the helm of Winooski; for a time, in the 1950s, he was deemed politically invincible. Kunin had her journalistic trial by fire when assigned to the meetings of city selectmen. With Rathe, a native of Quebec and a former weaver, as chairman, the use of the French language was so heavy as to make the proceedings almost incomprehensible. Only after the meetings, when sipping coffee with the selectmen, could Kunin start making sense of what she had just heard and witnessed.

If nothing else, this suggests that the idea of “Two Solitudes,” often applied to the English-French divide in Canada, was not confined to the northern half of the continent. In Vermont, too, and all across the U.S. Northeast, French-heritage people and their neighbors were often separated by language and ethnicity. Immigrants might have crossed the international border, but the real boundary was the cultural divide they encountered in their adoptive communities. That boundary was nourished by ignorance and misconceptions; it became self-perpetuating.

Still, there were opportunities for exchange: with the Irish in mixed Catholic parishes, with other workers in the few sectors with labor unions, with “old-stock” Vermonters through patriotic work and service during wartime, with all Americans through sports and popular entertainment. There were bridges that might enable Franco-Americans to live out and find fulfillment in their new, dual identity—if the winds of nativism could only relent. In the first half of the twentieth century, one person outdid all others in seeking to establish mutual understanding between Vermont’s two dominant cultures. This man, a dentist by the name of Joseph Denonville Bachand, straddled different cultural universes and attained a position of political influence that seemed inaccessible even to the mayors of Winooski.

Bachand was a native of the Eastern Townships of southern Quebec; his father served as mayor of Coaticook and then Sherbrooke. In 1902, Bachand crossed the international border and established his dental practice in St. Johnsbury, Vermont.[1] He married Juliette Cormier, the daughter of a prominent Sherbrooke merchant, in the city the following year. Bachand dedicated himself to the cultural life of the French-Canadian community of St. Johnsbury, including parish affairs. But, from a young age, he nourished larger ambitions that may have been inspired by his father’s own political success.

On July 1, 1914, at a French-Canadian celebration held in Rutland, Bachand momentarily departed from the usual remarks about heritage and cultural preservation to wade into partisan politics. The record doesn’t show how his audience reacted, but, in the larger world of state politics, controversy ensued. Bachand endorsed Allen Fletcher as the next U.S. senator from Vermont. The only problem was that Fletcher had not expressed interest in the Senate seat, let alone declared himself a candidate. Bachand’s remarks embarrassed the state’s Republican establishment and forced Fletcher to clarify his intentions. Our dentist’s remarks were not such as to endear him to the wheelers and dealers of Vermont.

If his first foray in politics was ill-advised, Bachand’s second attempt was promising. He had been involved in his local community for years and had served on the state’s dental examination board. There was also a substantial French-Canadian population in Caledonia County that might help propel him towards higher office. One hundred years ago, in March 1920, he announced he would seek a seat in the Vermont State Senate as a Republican.

His statements sometimes rang false, as when he remarked to farmers and workingmen that he too, as a dentist, had to earn his bread by “the sweat of [his] brow.” But there was also substance: he called for improved roads for automobile traffic, vocational training for veterans, state autonomy in the face of the federal Prohibition amendment, and increased state allocations for mothers. Clearly Bachand was at the “Bull Moose” end of the party, such as to earn him the endorsement of the American Federation of Labor.

Bachand faced an arduous primary fight. Outside of a select few urban centers, the Republican Party was the only path to power in Vermont. A person who received the party’s blessing during the primary season was generally assured of winning in November. The significance of the primary is highlighted by the crowded Republican field for the two State Senate seats into which Bachand entered. In fact, by July 1920, Bachand was complaining publicly about being “steam-rolled” by the GOP establishment: other candidates seemed to be getting preferential treatment.

Far from despairing, he doubled down on his outsider status, presenting himself as a figure without “wealthy or popular friends” to help him along. He supported his populist challenge to the establishment with a vigorous ad campaign in the local newspaper. He outdid his rivals by renting cars to bring women—then participating in their first election—to the town clerk’s office on the last day of voter registration.

It was, alas, in vain. Of the five candidates on the Republican ballot, the first two of which would earn the party nomination for the two open seats, Bachand finished last. To his credit, he did finish second in Hardwick and Lyndon and third in St. Johnsbury, but his political career and the opportunity to follow in his father’s footsteps would have to wait.

It is no easy task, with the records we have, to ascertain whether it was Bachand’s ideas, his manner of campaigning, his unconcealed ethnic identity, his limited connections, or some combination of the four that kept him from that State Senate seat. He certainly exemplified the limited political possibilities awaiting French Vermonters. He was one of a very small number of professionals and businessmen who, across the state, straddled the worlds of French-Canadian cultural life and civic involvement. Few had the social and economic capital to take part in mainstream U.S. politics.

In fact, rather than thinking of what Bachand lacked in his bid for public office, we might consider why so few individuals like him sought these higher functions. Surely, there were xenophobic voters; it also happens that few French Vermonters could claim middle-class status. With immigrant workers, those actually earning their bread by “the sweat of [their] brow,” so rural and dispersed outside of Winooski, Quebec elites tended to bypass the state altogether. It was to French Vermonters themselves to slowly ascend the socioeconomic ladder over the course of generations, this in a state with few opportunities for social mobility.

Bachand continued to immerse himself in the cause of survivance in the 1920s. Even Vermont felt the ripples of the Sentinelle Affair and the infighting that shook the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste may have led Bachand to become more involved with the Franco-American Foresters. If a breakthrough in electoral politics eluded him, he did benefit from occasional patronage. Through the 1920s and 1930s, a succession of governors—all Republican—appointed him as an official state representative at various functions, often agricultural fairs, in southern Quebec, not least in Sherbrooke.

In fact, despite the disappointment of 1920, Bachand stayed with the Republican Party (granted, by turning to the Democrats he would have condemned himself to political irrelevance) and slowly began to reap its rewards again. In the presidential election of 1928, while a large majority of Franco-Americans supported fellow Catholic Al Smith, Bachand was steadfast in his support of Herbert Hoover. The local newspaper even took the extraordinary step of publishing Bachand’s French-language plea to his compatriots in its original form. By the mid-1930s, his hour had come: on the strength of his multiple appearances at Quebec events, he was named to the Vermont Commission of Foreign and Domestic Commerce. In 1937, Governor George Aiken appointed him commission chairman.

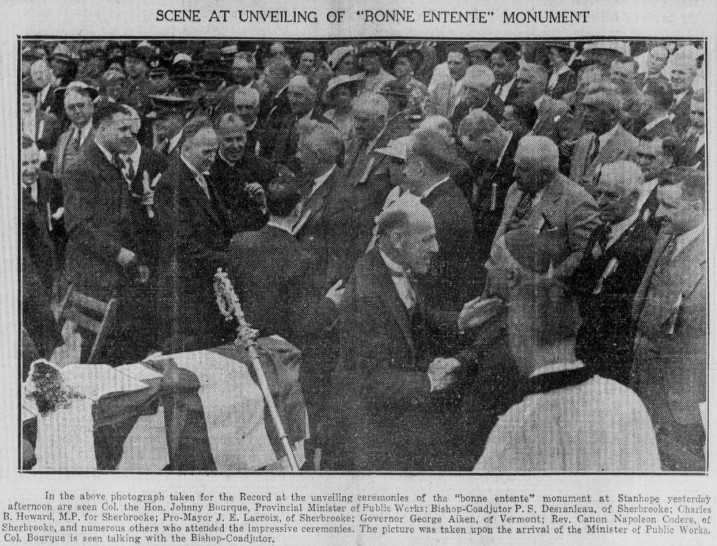

With Aiken’s eager support, Bachand now had the opportunity to put his vision of international amity into practice. The economic bonds between Quebec and Vermont could nourish cultural ties and vice versa; in the process, French Vermonters might gain greater recognition and legitimacy. In 1938, as I’ve discussed on The Conversation, the growing spirit of friendship culminated in the dedication of the Monument de la Bonne Entente, the “Good Will Monument” built in sight of the border in Quebec. Bachand and Aiken represented Vermont at that event.

The two men were again on Canadian soil late on August 31, 1939, when they first heard that Nazi Germany had invaded Poland. Bachand made additional trips to his home province during the war. It is during one of these visits that he declared himself “the pioneer of French cultural survival in Vermont”:

J’accorde toute ma fidélité et tout mon amour à ma contrée d’adoption, le Vermont. Mais soyez certains que jamais je n’ai oublié la foi et la langue de mes ancêtres. Et ce n’est pas sans fierté que je puis me déclarer le pionnier de la survivance française dans le Vermont.

This boast only served to show how sparse of a field he was in.

The Aiken–Bachand partnership had limited long-term impacts on Quebec–Vermont relations. It also had few tangible effects on Franco-Americans’ ability to enter the halls of power. In Burlington, Winooski, and other areas where they were concentrated, French Vermonters were more likely to support the Democrats. Their estrangement from the GOP became a vicious cycle of rejection and underrepresentation.

Bachand at least did his part in both respects and reaped some rewards. Boosted by his role as chairman of the Commerce Commission, he finally won election to the state legislature in 1938. He remained with the Commission and by the mid-1950s he was serving with two other men of French-Canadian descent, Reginald Abare of Barre and Wilfrid Boucher of Swanton. Bachand himself resigned in 1959 at the age of 75. He and his wife Juliette moved to Ormond Beach, Florida, just north of Daytona.

Joseph Denonville Bachand died on March 17, 1970, three days short of the creation of the Agence de coopération culturelle et technique, which in time morphed into the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. The opportunity to build international ties through a shared language and heritage was becoming a reality on a scale that Bachand could hardly imagine.

On March 23, another pillar of Franco-American life passed away: Henri Ledoux, a Nashua Democrat who had led the USJB during the turbulent 1920s and with whom Bachand had no doubt had sharp disagreements. Their near-simultaneous passing symbolized a passing of the torch that would become apparent gradually over the course of the subsequent decade.

Bachand was exceptional in many regards. The political campaign in which he was engaged a hundred years ago this summer reminds us of the barriers to Franco-Americans’ political ascent and influence in the halls power—and how few French Vermonters could achieve as much as he did.

But his struggle to broaden cultural understanding, to end the spirit of “Two Solitudes” was not an entirely lonely one. In Winooski, St. Johnsbury, and beyond, there were opportunities to listen and to dialogue, and some brave souls did just that. We may hope that historians will continue to rescue from obscurity the individuals—French, Yankee, and other—who tended to this hard business and who can inspire us to build figurative “Good Will Monuments” in our own day.

Much of J. D. Bachand’s career, including his 1920 campaign, is chronicled in St. Johnsbury’s Caledionian-Record. The Collections patrimoniales on the website of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) provide keyword-search access to historical newspapers; many detail the presence of a Vermont delegation at public events in Quebec in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s.

Interested in learning more about French Vermonters? Check out the following posts:

- Early Canadian Migrations to the United States

- Those Other Franco-Americans: Barre, Vermont

- Review: Licursi and Paquette, Franco-Americans in the Champlain Valley

- Franco Pioneer Russell Niquette

[1] In the 1910s, his practice was located in St. Johnsbury’s Pythian Block, which still stands.

Leave a Reply