What’s in a name? For illustrious Quebeckers of the late nineteenth century, we might think that it was destiny. Honoré Mercier, Faucher de Saint-Maurice, and Prosper Bender, all born in the 1840s, each had a name to match his personality and preeminence.

So it was with Honoré Beaugrand, who survives in Quebec’s historical memory chiefly as the author of La Chasse-Galerie and Jeanne la Fileuse.

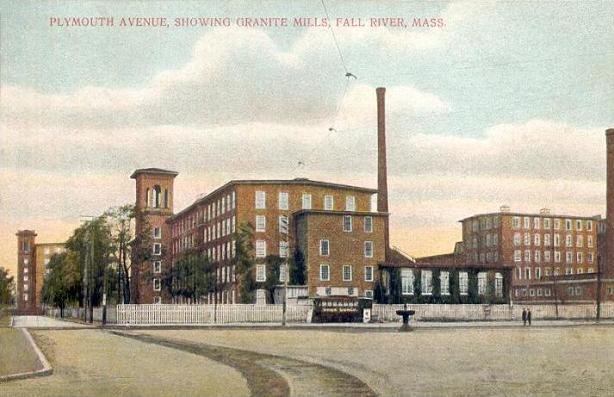

Those works are a rather small part of Beaugrand’s life story. As a young man, he travelled to Mexico and fought for the imperial forces during the invasion of the 1860s. He spent much of the 1870s in the United States. He was a pioneer of the French-language press and edited several newspapers in Fall River, Massachusetts, an industrial boomtown then swelling with immigrants from Quebec.

Back in his native land at the end of the decade, Beaugrand founded the great Liberal daily, La Patrie, which would soon find an acerbic conservative adversary in Jules-Paul Tardivel’s La Vérité. As next week’s post will show, Beaugrand’s Liberal inclinations were already quite explicit at the time of his writing Jeanne la Fileuse.

In the mid-1880s, Beaugrand was elected mayor of Montreal. His campaign and administration are best remembered for his defense of compulsory inoculation in the midst of a smallpox epidemic. (It was so bad that U.S. newspapers expressed new worries about Canadian immigration and what it meant for American public health.)

After leaving office, Beaugrand continued to publish and to challenge Quebec’s clerico-conservative politics.

It was at the end of his time in Fall River that Beaugrand published Jeanne la Fileuse (“Joan the Spinner”), which was tellingly subtitled, épisode de l’émigration franco-canadienne aux États-Unis (“a chapter in French-Canadian emigration to the United States”).

Jeanne la Fileuse is a novel, but it takes very few liberties with the history in which it is situated. Without giving too much away to those who plan to read this classic, much of the action takes place along the St. Lawrence River north of Montreal. We see how young men still seek to supplement a farm’s earnings and to prepare to marry by going en-haut—upriver to work as lumberjacks and log drivers.

The plot revolves around young lovers whose prospects of a shared life momentarily succumb to political resentments inherited from the Rebellion of 1837. When Jeanne Girard loses her father, unable to reach out to her fiancé, she has little choice but to follow a local family to New England. With them she works in the mills… until a final plot twist grounded in real events settles the matter for all. (Jean-Louis Lessard shares the spoilers here; so does Brendan Shanahan, with additional analysis, here.)

The novel is a two-parter. In the middle lies a long digression expressing Beaugrand’s view of emigration and its political context. This, after all, was not a dispassionate endeavor meant merely to regale Quebec readers. Beaugrand used a Quebec that everyone knew, a history familiar to all, to make a very clear point about emigration and its causes.

The excerpt will conclude next week with additional political context. I have found no English translation of this novel, a sad fact that I hope owes to some oversight on my part. What follows, then, is my own translation.

~ ~ ~

A migration possibly unparalleled in the history of civilized peoples has lately taken place in the countryside of French Canada. Thousands of families have gone into exile, pushed as if by an inescapable force towards the industrial workshops of the great American republic. Some statesmen have spoken out to alert us to this new threat to Canada’s prosperity, but such calls have left no echo and emigration has continued in its depopulating enterprise. It is said that over five hundred thousand French Canadians now live in the United States, that is, more than one-third of those who belong to the French-Canadian race in America. If these numbers are accurate, and there is little reason to doubt them, it is easy to understand the disastrous effects of this mass exodus of its inhabitants on the material prosperity of the country and on the influence of the French nationality in the new Confederation. […]

Around 1825, a migratory movement began to affect the parishes on the south shore of the St. Lawrence, downstream from Quebec City. This movement resulted from the establishment of steam-powered sawmills and the rise of the construction lumber trade in the State of Maine. This state, which resembles Canada in every respect, particularly in its climate and agricultural products, had developed the American republic’s premier shipyards for a merchant fleet growing at a stunning pace. A great number of Canadian families drawn by the lure of better income abandoned farm work to seek among their neighbors in Maine the well-being they lacked in Canada. Most of these families settled in the towns and villages of Frenchville, Fort Kent, Grande-Isle, Grande-Rivière, etc., where their descendants still live and preserve the language and customs of the old country. The proximity of Canadians parishes and settlements has done a great deal to uphold in these good people love of the home country.

The revolution of 1837-1838 forced many families from the parishes along the Richelieu River to leave Canada. Most of the “Patriotes” found refuge in Burlington, Plattsburg, Whitehall, Albany, and New York City. But, as this migration owed to political causes and the number of emigrants was relatively small, we will move on. The emigration of which we speak, here, is an emigration of suffering and hunger. The other movements were but partial and insignificant.

A few years later, around 1840, the lumber trade between the United States and Canada produced another migratory current, this one to the towns along Lake Champlain in the states of New York and Vermont. Rouses Point, Burlington, Plattsburg, Port Henry, and Whitehall consecutively welcomed this contingent of French-Canadian emigrants. The largest number of these emigrants worked on the docks, loading and unloading wood and grain for the Canadian trade. Each of these towns still holds a fairly large population of French-Canadian origin, although the lumber trade is far from what it was twenty to thirty years ago.

Some of the families that had emigrated to American towns close to the border pushed towards the interior of the New England states and found work in the wool, linen, and cotton factories that are the wealth of the Eastern states. This was the beginning of the great migratory movement that has haphazardly thrown into American factories the five hundred thousand French Canadians who left the native soil to seek, in a foreign land, the work and bread that they lacked in Canada. This movement began about twenty years ago [circa 1858], but it is chiefly since the end of the Civil War, in 1865, that emigration has assumed truly frightening proportions for the material well-being of the Province of Quebec.

Regular readers may be interested in reading my contribution to the new blog of the French-Canadian Legacy Podcast, titled “Why I Tell the Franco-American History.” On a more polemical note, I also recently wrote on “The End of Canadian Imagination” for Canadian Dimension. More on Beaugrand next week.

Interesting contribution. I remember him as having founded newspapers in Fall River, and also St. Louis, I believe, and maybe New Orleans. I organized a round table for an ACQS mtn in Portland, Maine over 10 years ago ti reminisce about the glory days of FR. There were four of us: one who had had a long expérience with his French radio program; one who had inherited the ownership of the last FR French newspaper. For some reason, I thought he had founded l’Indépendant, but from what I’m reading today,his paper had another name. Maybe it was the Anna Duval Thibault which was connected to l’Indépendant.

Thank you for your comment, Paul. The leading figure in the founding of L’Indépendant was Hugo Dubuque. Your roundtable sounds like a terrific event; I wish I’d had a chance to experience it. If this was the ACQS meeting held in Portland in 2016, we may have crossed paths.