An earlier version of this essay appeared in the fall 2021 issue of Le Forum, the quarterly publication of the Franco-American Centre (University of Maine). Please cite appropriately.

* * *

In early nineteenth-century Michigan, a Chippewa couple adopted four-year-old Leah Campeau, whom they had found wandering alone in the wilderness. After the War of 1812, Campeau, raised as an Indigenous girl under the name Neamata, fell in love with Bruce Marshall, an employee of the American Fur Company. Marshall, however, fell for her white sister, who had grown up in their biological parents’ household and had no knowledge of Neamata. A “giant trapper” named Jacques Cautier (yes, Jacques Cautier) was jealous of Marshall and vied for Neamata’s affection, but the two men won each other’s esteem and Cautier began to connect the dots. With this French Canadian lay the moment of recognition between the Campeau girls as well as the solution to the love triangle.[1]

If this sounds like the plot of a soap opera, that’s because it is. Neamata, Marshall, and Cautier were fictional characters in The White Squaw, a play that made its stage debut in New England in 1909. Its author and lead actress, Della Clarke, contributed to the myth of the “vanishing Indian,” a longstanding trope anchored by the literary fiction of Cooper and Longfellow. But Clarke’s work helped blaze a trail in other regards: like a pair of contemporary plays, it placed French Canadians front and center and enhanced their visibility across the United States.[2]

Playing to the Northern Mystique

We often read back in time the sense that Franco-Americans are invisible. That was not the case in the early decades of the twentieth century. Beyond the sheer number of French Canadians and their economic significance in the U.S. Northeast, immigrants from Quebec and their children attained positions of influence at the municipal and state levels. Their annual June 24 festivities were noticed and they increasingly took part in labor activism. The controversies that pitted them against Roman Catholic bishops won widespread coverage in the mainstream U.S. press.

French Canadians also found representation across the United States through theater and film productions. The Ontario-born novelist Gilbert Parker spurred a whole cottage industry from French Canadians’ frontier experiences, with Della Clarke quickly capitalizing on the emerging genre. From novel to stage to screen, canadien characters populated Americans’ artistic universe.

In these productions, French Canadians provided exoticism; collaboration and conflict across cultures enriched the plot. The setting mattered just as much. The stories were not set in the sooty mill cities of New England or on quiet farms along the St. Lawrence River. With the exception of The White Squaw, playwrights also turned away from the Western frontier, which long captured the American imagination. By the 1890s, experts were claiming that the frontier had closed. From the Plains to the Pacific, Americans had, it seemed, tamed the environment and conquered the original inhabitants. The apparent triumph of “civilization” offered few romantic visions. Another frontier would supplant the West.[3]

Perhaps due to the Klondike gold rush (1897-1899), writers and audiences became enthralled by the mysteries and perils of the great Canadian North. It was in this era that Jack London won acclaim not least as an exponent of the Northern mystique. In these wilds, writers implied, the culture and claims of “Indians” were yet to be extinguished; the people of European descent who penetrated those endless expanses were often trappers or miners and lived by their own code of justice. Stories set in this imagined Canada also brought the Mounted Police and the trading posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company into the American cultural landscape.

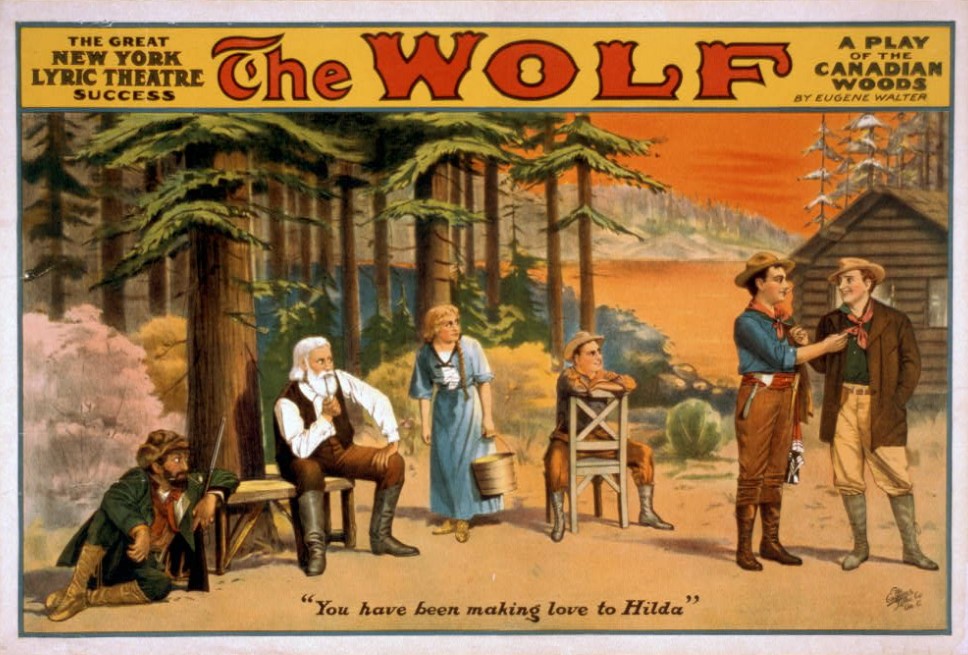

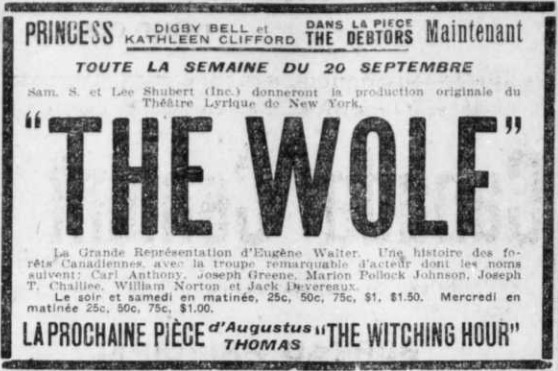

Playwright Eugene Walter’s The Wolf, which made it to the stage in 1908, helped establish both the genre and the fictional setting. Walter was even called the “Columbus of a new field of drama,” which, considering the treatment of Indigenous peoples both historically and in literature, was a little too on-the-nose. A critic stated that The Wolf “was brought out after playrights [sic] of all degrees had dipped their pens into vast avenues of explorations, at a time when it was thought there were [but] a few worlds to conquer in the matter of locale, color, atmosphere and theme. There had been a flood of Western dramas, filled with action and virility of the wild plains and hills, there had [been a] dainty offering from the drawing room, there had been society plays and problem plays, and search was turning to the other side.”[4]

Defining the French

French-Canadian characters occupied this literary landscape. In many parts of the continent, people of French descent had blazed a trail for other European agents of empire. Fur traders had overcome considerable natural challenges and established relations—not always cordial—with the Indigenous nations of the West. Well-read Americans would have been acquainted with the voyageur character thanks to the historical work of Francis Parkman. Novelists and playwrights expanded that image for a wider public.[5]

As Jason L. Newton has argued, ideas about French Canadians’ inherited suitability for certain types of work were prevalent in the economic field.[6] This was not perfectly mirrored in the performing arts. The White Squaw and The Barrier evinced a fascination with racial identity—specifically Native peoples’ relationship to whiteness. But early twentieth-century plays did not establish that French Canadians were a people inherently of the wilderness, for the wilderness.

The range of attributes of French-Canadian characters suggests that playwrights were more interested in successful plays involving dramatic tension, action, and romance than in ethnic commentary. Male figures were often trappers or miners, but they were more likely to be heroes than villains and they were more complex than we might expect. This is not to say that these ethnic representations on stage and screen were without the “cultural shortcuts” that nourish stereotypes and even prejudice. But, at the same time, these depictions formed a relatively bright spot in a long arc of Anglo-Protestant exclusion.

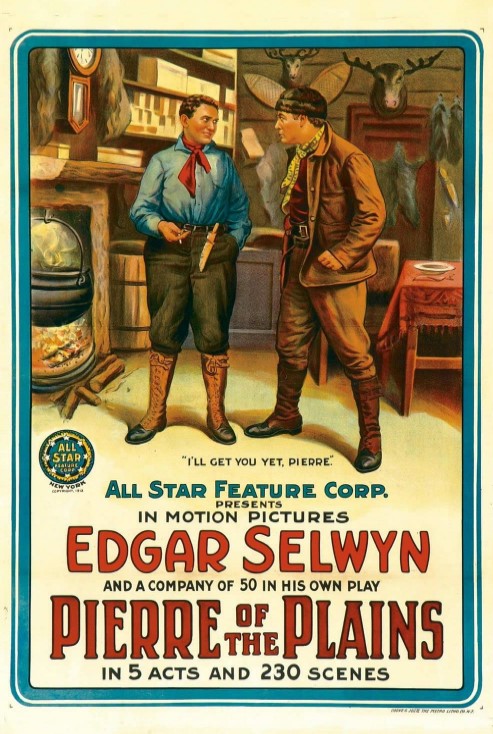

Gilbert Parker dedicated The Lane That Had No Turning, a novel published in 1900 and later a film, to Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier. He praised Laurier for his efforts towards amicable English-French relations in Canada. He added, “In a sincere sympathy with French life and character, as exhibited in the democratic yet monarchical province of Quebec, or Lower Canada (as, historically, I still love to think of it), moved by friendly observation, and seeking to be truthful and impartial, I have made this book and others dealing with the life of the proud province, which a century and a half of English governance has not Anglicised.” The praise continued: Parker celebrated the frugality, industry, and domestic virtue of French Canada.[7] These were not empty words; Parker’s approach was lauded by Quebec elites. Université Laval awarded him an honorary degree in literature in 1912 and with reason. The stage adaptation of his Pierre and His People (retitled Pierre of the Plains) had won the plaudits of the francophone press, which recommended it to its readers.[8]

What’s more, of the lead character in Pierre, Parker explained, “[h]is faults were not of his race, that is, French and Indian, nor were his virtues; they belong to all peoples.” Parker could not escape the language of race, and we cannot exonerate him fully from ethnic preconceptions, but he seemed to reject a racial essentialism that was then quite prevalent.[9]

The theatrical success of Pierre and The Wolf inspired other plays in the same vein—The White Squaw, for instance. Although the story unfolds in Quebec, Eugene Presbrey’s adaptation of Parker’s The Right of Way, first performed in 1907, preceded all of them and helped steer character development across the genre. The character of Joe Portugais served as a template for French Canadians who would be transplanted, fictionally, in the Northwest. Portugais, a critic opined in 1910, “is a type that might easily be burlesqued, but of whom intelligent representation is extremely difficult.” Actors’ search for a fair portrayal of the French Canadian had begun.[10]

Authenticity in Representation

We are currently in the midst of a fierce debate about ethnic representation in literature and the performing arts. Should characters of a certain culture only be played by actors who share their background? Can artists produce an authentic and respectful depiction of other ethnic groups? One of the great virtues of art is to enable creators to explore different identities and to nourish empathy for other cultures. At the same time, minority groups may feel that their story is being misinterpreted, distorted, or commodified. When deploring their lack of visibility, some Franco-Americans cite the representation given to other groups in, say, The Godfather or Gangs of New York. We may, however, justly wonder how a French-Canadian equivalent to these films would be received, for these rely on well-worn ethnic tropes.

We can raise this question retrospectively because few people of French descent had creative input in early twentieth-century productions, even if characters were molded by the real-life encounters of English-Canadian artists (Parker, Edgar Selwyn, Nell Shipman). Annette de Foe (born Gertrude Aucoin in Louisiana) played a French-Canadian girl opposite Mitchell Lewis in The Timber Wolf. The Detroit-born Frank Campeau played a secondary role in the 1922 film adaptation of The Lane That Had No Turning.[11] They were exceptional.

Actors at least strived for verisimilitude. Theodore Roberts, who long played Joe Portugais, crossed the border specifically to study French Canadians and master the role.[12] Helen MacKellar, who became Mannette Fachard in The Storm, a Broadway sensation of the late 1910s, also gave serious thought and study to her role. She had learned French in school in Spokane and Chicago, but soon realized her accent was all wrong for the role she had accepted. She spent a summer in French-Canadian circles to master the language, its idioms, and its intonations.[13]

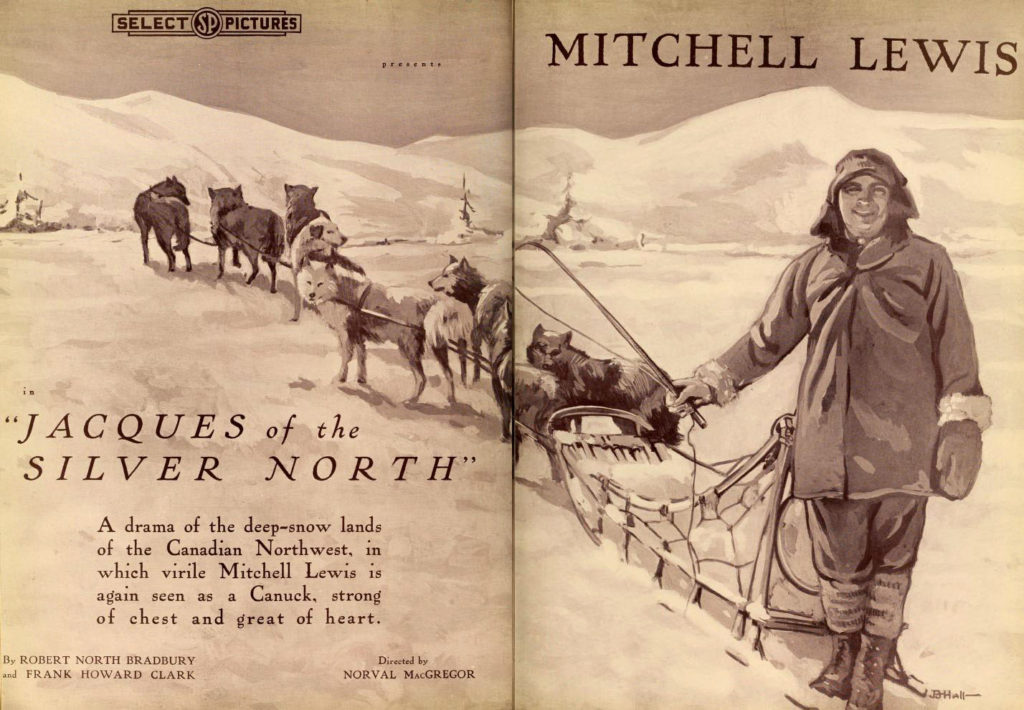

Stage and screen actor Mitchell Lewis probably played more French-Canadian characters than anyone else and developed the Portugais figure. He played Cautier in The White Squaw and took on French-Canadian and Métis figures in The Barrier, Sign Invisible, Code of the Yukon, and The Timber Wolf.[14]

From one role to the next, Lewis was the quintessential rugged but friendly giant. His part in The Barrier—a novel by Rex Beach published widely in newspapers in 1909—is informative. Beach set his story in Alaska in the era of the gold rush. A main character was ‘Poleon Doret, who instantly earned the admiration of a blue-eyed Southerner for whom proper lineage was everything. Doret “stood a good six feet two, as straight as a pine sapling, and it needed no second glance to tell of what metal he was made. His spirit showed in his whole body, in the set of his head, and, above all, in his dark, warm face, which glowed with eagerness when he talked, and that was ever—when he was not singing.”[15] The film version was released eight years later, with Lewis starring as the “lovable” Frenchman. It was through this character’s “nobility and self-sacrifice” that the girl for which he cared could find love and happiness.[16]

We have yet to unearth signs that Franco-Americans took issue—if in fact they did—with Pierre of the Plains, The Wolf, The White Squaw, and other productions where cultural others depicted them. Theirs was a different historical moment when representation by English Canadians and Anglo-Americans was an honor of sorts. Additionally, stories about innocent French-Canadian girls torn between two lovers, or about tough, resourceful men, appealed as much to people of French heritage as they did to the wider audience. These plays and films also served as a point of entry to the culture, the beginning of a conversation. In the U.S. Northeast, where nativist prejudice persisted, a Jacques Cautier could highlight French people’s historical presence on the continent and offer mill workers exotic and noble parentage.

The French—Far and Wide

We cannot underestimate how prevalent these images were. Pierre debuted in Toronto; its cast played in Montreal, then under the bright lights of New York City, and the tour went on. By 1911, it was being performed in San Francisco. In 1914, it became a widely-distributed film with actor Edgar Selwyn reprising the role that he had made famous on stage.[17] The Wolf was played at least as far as Conway, Arkansas.[18]

That visibility grew with film. In 1917, movie goers in Oklahoma turned out to watch Lewis as Doret. Like Lewis, silent-era superstar Monroe Salisbury more than once played a Canadien. A star of The Flame of the Yukon (1917), Dorothy Dalton then became Colette Brissac, the orphaned “daughter of a French-Canadian miner” in The Idol of the North (1921). Nell Shipman played “a beautiful, brave French Canadian girl” in The Girl from God’s Country (1921).[19]

These are but a small sample of a cultural craze that began in 1907-1908 and endured to the mid-1920s. The copycats were such that as early as October 1908, one critic had had enough of tales of the Canadian Northwest. Unimpressed with Pierre of the Plains, Charles Darnton complained: “The same old habitant, the same old accent, the same old girl whom two men love, the same old mounted police who seem to be kept busier than the local contingent, and the same old runaway and fight all go to make up the same old story. Canada never was an alluring region for stage purposes, and now that it has become the stamping ground of two-dollar melodrama it is a weariness to the spirit.”[20] Darnton’s was a voice in a different kind of wilderness. Thriving stage production that toured the country and countless films are evidence that audiences felt differently about the genre.[21]

Historical Questions

As noted, widely-travelled plays and films furthered ethnic visibility. Those portrayals were at odds with the lived experience of French Canadians of the day; they also skewed history for dramatic effect. The use of the type of French dialect speech popularized by William Henry Drummond was not always flattering. On the other hand, these films and plays do not fit neatly in our received narrative about U.S. nativism; in many respects, they redeemed French Canadians and they matter because they were culturally ubiquitous and more widely accessed than the mythmaking of a small intelligentsia. How they may have counteracted xenophobia requires further exploration.

People of French descent were not merely fictional participants in these productions; they were also consumers of a genre that could be viewed in New England as in any other region of the country. They must have been eager to see themselves on the big screen. Like political involvement and sporting events,[22] Hollywood cinema reminds us that Franco-Americans did not live in a cultural silo that suddenly burst after the Second World War. French-Canadian immigrants and their descendants engaged, even in limited ways, with American mass culture in the early twentieth century. The intersection of ethnic and “mainstream” culture demands greater exploration.

At last, to circle back to The White Squaw, we must also continue to delineate the representation of French-Canadian, Métis, and Indigenous characters in all of these works. We may notice, as initial evidence suggests, that these characters were subjected to far different literary treatment. That the French Canadians benefitted from a kinder portrayal than Native peoples indicates that the former had acquired certain cultural privileges as a colonizing people that could be fully white.

[1] Knoxville Sentinel, February 23, 1910; Tacoma Sunday Ledger, magazine ed., June 26, 1910.

[2] The Journal [Meriden, Conn.], September 14, 1909; Fall River Daily Evening News, September 24, 1909; Bangor Daily News, October 16, 1909.

[3] Frederick Jackson Turner made this argument about the end closing of the Old West in “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” in 1893.

[4] Quebec Chronicle, January 22, 1909.

[5] Parker was in fact classed alongside Parkman and William Henry Drummond, whom he knew personally, as a popularizer of French-Canadian history and culture. Prosper Bender, who straddled the cultural line, would have been another such figure. See “The Pioneers of Eastern Canada,” Educational Record of the Province of Quebec, May 1912, 184-188.

[6] Newton, “‘These French Canadian of the Woods are Half-Wild Folk’: Wilderness, Whiteness, and Work in North America, 1840-1955,” Labour/Le Travail (2016).

[7] Gilbert Parker, The Works of Gilbert Parker: The Lane That Had No Turning, Imperial Edition, Vol. XI (New York City: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916), v-vii, xi.

[8] “Doctorats honoris causa,” Université Laval, 2021, https://www.ulaval.ca/notre-universite/prix-et-distinctions/doctorats-honoris-causa?tid=40 (accessed 2021-08-21); La Presse, September 26, 1908; Le Samedi, October 3, 1908. See, on later cinematic depiction of Franco-Americans in Quebec, Pierre Lavoie, “Moi, c’est l’Autre: L’histoire des Franco-Américains dans la culture populaire télévisuelle et cinématographique au Québec (1949-1992),” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française (2018).

[9] Parker, The Works of Gilbert Parker: Pierre and His People – Tales of the Far North, Imperial Edition, Vol. I (New York City: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916), xv-xvi. John C. Stockdale explores the blind spots in Parker’s mental landscape in “The French Canadian According to Gilbert Parker,” Modern Language Studies (1973).

[10] Whereas other plays offered a more complex depiction of French Canadians, Portugais was a “child-like, brutal, half-bestial man, simple-minded, full of a joyousness which had too few chances to show itself, loving with almost reverent awe, Charley Steele, the man who had saved his life.” It may be of some solace that Steele was an “unscrupulous lawyer” leading a life of dissipation, and each man had his turn at redemption by saving the other. See San Francisco Examiner, March 23, 1909; East Oregonian [Pendleton, Or.], evening ed., January 12, 1910.

[11] Fifi d’Orsay (the stage name of Yvonne Lussier) had yet to begin her career. See Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1921; News and Observer [Raleigh, N.C.], August 13, 1922; New York Times, December 4, 1983.

[12] Examiner, March 23, 1909.

[13] New York Tribune, November 9, 1919.

[14] Fitchburg Sentinel, October 28, 1909; Tulsa Democrat, August 6, 1917; Spokane Chronicle, March 30, 1918; Norwich Bulletin, June 14, 1920; Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1921.

[15] Fort Worth Star and Telegram, January 1, 1909 and January 2, 1909.

[16] “‘Barrier’ Proves Gripping Film,” Tacoma Daily Ledger, May 13, 1917, 6.

[17] The Gazette [Montreal], September 23, 1908; The Sun [New York City], October 13, 1908; San Francisco Examiner, alternate ed., August 1, 1911; Alaska Citizen [Fairbanks], July 13, 1914.

[18] Log Cabin Democrat [Conway, Ark.], March 9, 1914.

[19] Tulsa Democrat, August 6, 1917; Washington Herald [D.C.], September 22, 1918; Dallas Express, August 16, 1919; Los Angeles Times, July 2, 1917; Norwich Bulletin, July 9, 1921; Courier-Post [Camden, N.J.], December 15, 1921.

[20] Evening World [New York City], October 13, 1908.

[21] “Canuck chic” did survive in some form; many plays and films became standards that were remade. Pierre of the Plains was adapted to the radio in the 1920s and inspired a second movie of the same name in 1942. See Quebec Chronicle, April 10, 1924; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 30 1942.

[22] See, on sports’ impact on acculturation, Richard Sorrell, “Sports and Franco-Americans in Woonsocket, 1870-1930,” Rhode Island History (1972).

Pingback: An Introduction to French-Canadian Folklore & Franco-American Culture – Moderne Francos