An earlier version of this essay appeared in the winter 2021-2022 issue of Le Forum, the quarterly publication of the Franco-American Centre (University of Maine). Please cite appropriately.

* * *

Few years in American history carry the same symbolic significance as 1848, which set the stage for what was to come in subsequent decades. Women met in Seneca Falls, New York, to chart a more egalitarian direction in gender relations. Immigration from Ireland reached its highest level. Continued political stability while revolutions swept across Europe boosted Americans’ confidence in their republican experiment. So did victory in the Mexican-American War: the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, signed in February 1848, transferred half of Mexico’s territory to the United States. Finally, a New Jersey native named James Marshall discovered gold on a branch of the American River west of Sacramento. His find transformed the West. The following year, approximately 100,000 people arrived in California; they live on in our history books as the Forty-Niners.

People were on the move, and that’s where “national” U.S. history begins to transcend political boundaries. The discovery on the American River drew fortune-seekers half a world away. Britain’s North American colonies could not escape the tantalizing reports. French Canadians were already spilling out of their historic homeland along the St. Lawrence River. Since the Rebellions of 1837-1838, they had sought new opportunities in Illinois, New York State, and northern New England in ever-rising numbers. Desperate or ambitious, they learned of the events at Sutter’s Mill and heard the call of the California gold fields. In the fall of 1849, a steady stream of migrants linked Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) and California. Canadian and American affairs were becoming entwined on a truly continental scale.

La folie de la Californie

Outmigration attracted the scrutiny of Canadian policymakers in the spring of 1849. If the final version of their report is any indication, California was of no concern to members of the colonial legislature. It seems the prospect of an easy fortune on the other side of the continent was not a leading cause of emigration.[1] We do know anecdotally that some French Canadians from today’s Centre-du-Québec region did start for California in the early months of 1849.[2] But it was a growing number of alluring news items about the American West in the summer and fall that stirred Canadians’ interest—and that threatened to turn a policy challenge into a national crisis.

The publication of a Catholic missionary’s letter in July 1849 helped drive curiosity. After a decade of service along the Richelieu River, Father Jean-Baptiste Brouillet had agreed to missionary work under Augustin Magloire Blanchet, the newly-appointed bishop of Walla Walla in Oregon Territory, in 1847. The two prelates joined tens of thousands of Americans and immigrants who had undertaken the cross-continental trek on the Oregon Trail, a six-month journey that tested even the hardiest and most resourceful traveler. In 1848, as the human deluge began to fall on California, Brouillet volunteered to travel south to minister to the miners.

The wage rate and cost of living had exploded, wrote Brouillet. But fortunes were being made. In December, in San Francisco, he had seen “several of our Canadians from Oregon who were returning after working a little under two months, and each had over $2000 in hand.” The climate and soil of California were equally favorable. Inadvertently, perhaps, reports like Brouillet’s encouraged young men to go West.[3]

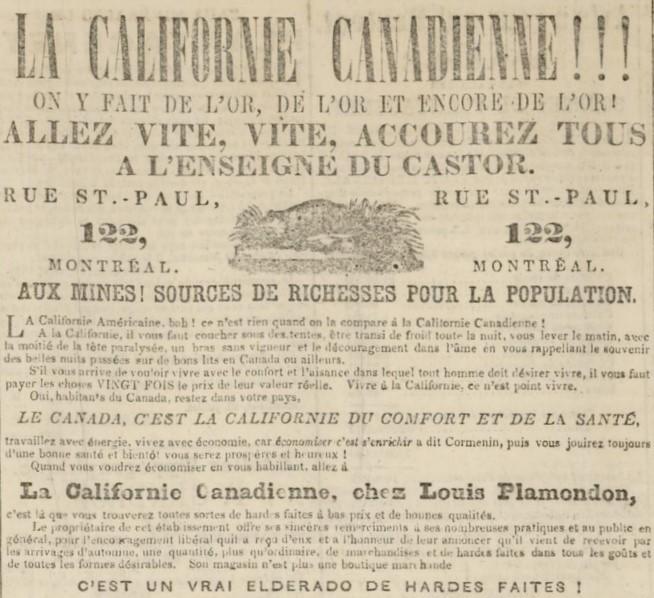

French-language newspapers expressed ambivalence about migration, but, in the early days of the gold rush, some like L’Avenir proved sanguine about Canadians’ prospects. So it was in September 1849 when five men from Sainte-Elisabeth—C. H. Beaulieu, O. Brissette, Alexis Pépin dit Lachance, Joseph Robillard, and Maxime Goulet—departed for California. “We disapprove of large-scale Canadian emigration because it hurts the country,” L’Avenir declared, “but it will be a delight to see a certain number of our young compatriots set off to the gilded regions of California, and play a role in the rush to riches that draws in this country people from all parts of the globe. Those who do not have the means to leave at this moment and travel in comfort are ill-advised to leave, as we have stated. We recommend that they stay here and settle for visiting the ‘Canadian California’ [the riches] of Mr. Plamondon’s store [in Montreal].”[4]

For a time, the press’s cautious tone was no match for the lure of easy gains. By November, “California fever” had reached Quebec City. L’Avenir printed a list of people who had boarded the Rory O’Moore and the Panama with California as their ultimate destination. These passengers were predominantly of British and Irish origin, but in their midst were such names as Rousseau, Garneau, Lévesque, Lacroix, Gagnon, Picard, Dionne, Ledroit, and Duchesnay.

Letters from New York City added to that number and again named names. On November 12, many French Canadians set sail aboard the St. Mary and the Washington; among them were former residents of Montreal, Saint-Rémi, Sainte-Thérèse, Baie-du-Febvre, Nicolet, Saint-Michel-d’Yamaska, Bécancour, Saint-Grégoire-le-Grand, Stanfold Township, Trois-Rivières, and Gentilly. The exodus of young, adventurous men had touched nearly all regions of Lower Canada. L’Avenir concluded that “the number of emigrants to California is increasing and gold fever appears to be just beginning in Canada. Everyday our office is besieged by people seeking information about the marvel of the American Republic.”[5]

Journeys

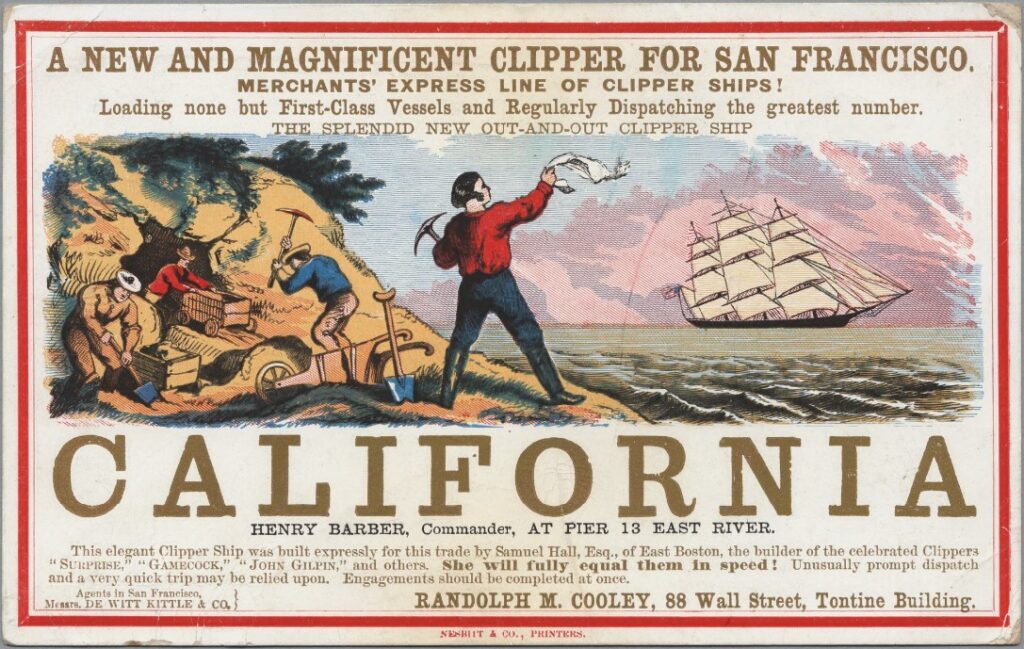

Published reports suggest that most migrants chose not to follow in Father Brouillet’s footsteps. Foregoing the difficult journey across the Plains and Rockies, they opted instead for the oceanic route. They boarded ships in Quebec and New York; some vessels committed to the long route around Cape Horn, others docked in Chagres, in Panama, leaving passengers to portage to the Pacific shore and take a second ship north to California.

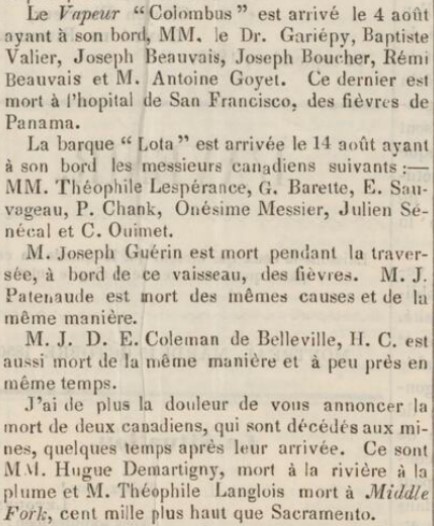

The oceanic trip did not require any less planning than the overland one. Writing from New York City in October 1849, Dr. A. J. Desrivières explained that California-bound steamers were fully booked until December. Anyone leaving Lower Canada without making reservations would waste their precious savings in New York while they waited for a berth to open. Another writer added that emigrants should travel in large groups for security and mutual support. What’s more, not all ships and captains were alike—not all would reach their destination in a safe and timely manner. This is to say nothing of poor drinking water or food supplies and seasickness, which weakened passengers. Disease thrived. The following year, a Forty-Niner with the last name of Robert left California with a rather large stack of letters from fellow expatriates. He wouldn’t make it home. He died of cholera in Panama. What a life, and what an end for a little guy from Saint-Jean.[6]

A small controversy that erupted in the fall of 1849 highlighted other challenges. A Canadian merchant named Robillard was conducting business in what is today the financial district in Lower Manhattan. Having lived in New York for some years, he offered to provide guidance and support to prospective emigrants to California. He may have been well-intended, but he was not above exacting a certain fee and setting terms for his services. Five California-bound Canadians who felt misled about Robillard’s work complained publicly.[7]

Others quickly came to Robillard’s defense; he had provided valuable support to a group of Forty-Niners from St-Jérôme and Montreal: Louis Beauchamp, François Bonacina, brothers by the name of Innes, a Dr. Larocque, and others identified by their last names—Archambault, Grenier, and Guénette. Support also came from Father Charles Chiniquy, who would soon play an essential part in the French-Canadian colonization of Illinois. He stated that it was thanks to Robillard that his brother Achille Chiniquy had been able to set off to California. It’s certainly clear that there were characters far worse than Robillard—swindlers, so-called travel agents, and shipping lines taking advantage of young people who spoke little English and who knew little about their destination or how to get there. Robillard himself added that there were “runners” who, as far north as Albany, sought to fleece travelers.[8]

“Misery and Privations”

From this point forward, reports from New York City and California did not get much better. Already, in early December 1849, Lower Canada’s newspapers were sharing “Mauvaises nouvelles de la Californie.” Emigrants discovered a West far different from the one they had imagined. From the muddy streets of San Francisco, many people had to journey to the Sierra Nevadas on foot. The heat was often unbearable; people died along the way. One young man from New Hampshire who collapsed from heat stroke asked, in his final words to a travel companion, “How is it possible that I’ve come here to die?” Survivors had to contend with the highly-inflated cost of living and the struggle to acquire necessities. Some had lost a small fortune simply by traveling to California and keeping themselves fed. Now they wished to earn just enough money to make it back to friends and family at home. Although the gold rush was seen as a get-rich-quick scheme, one wonders how much money left Lower Canada, in 1849-1850, as people went abroad with what they could amass, only to promptly lose it.[9]

Tellingly, in June 1850, a new letter from Father Brouillet, who would soon be returning to Oregon, offered a vision far different from the prior year’s. He alerted his compatriots to the declining fortunes of emigrants—a warning, at last.[10] In Saint-Jean, Gabriel Marchand confirmed the changing narrative in letters to his son Félix, a future premier of the Province of Quebec. In one missive, the elder Marchand highlighted the ordeal of the overland journey that acquaintances had attempted. “The accounts from California as to gold gathering are good,” he wrote. “But, misery and privations to their full extent [are] in fact represented as above human indurance [sic].” One wonders whether Marchand was simply relaying available news reports to his son or trying to deter him from also trying his luck in the West.[11]

About the same time, Montreal notary J. A. Labadie shared with L’Avenir a letter from a friend who was now in California. The author, probably François Bonacina, returned to common complaints about California, but now with the benefit of having personally experienced the gold rush—the heat, the debilitating work, the cost of living, and so forth. He also had a great deal to say about the throngs in San Francisco and the gold mining regions. Many were ignorant, of the lowest morals and passions. This, the correspondent explained, was a Sodom of the most diverse crimes. Meanwhile, Victor Beaudry’s letters regularly added names to the growing death toll; Louis Beauchamp communicated similar reports, including the drowning death of Chevalier de Lorimier’s brother.[12]

The story of French-Canadian migrations cannot, however, be reduced to sorrow and privations. It is also a tale of resilience and collaboration.

Digging In

From the Hudson River and New York City to Panama and California, Canadians found one another. “F. B.” wrote home of time spent with the Innes brothers, Mexican War veteran Robert d’Estimauville, and others on the west coast of Panama while they awaited the arrival of the next northbound ship. He added that the Canadian miners in California had concentrated at Mormon Island.[13] A later letter from Victor Beaudry stated that 60 Canadians were now in San Francisco; many of them would soon set out for the gold fields west of Sacramento. Like Robillard in New York City, Beaudry was well-informed and could provide guidance to emigrants. Joseph Rassette, who established a hotel in San Francisco, would earn the gratitude of travelers in the same role.[14]

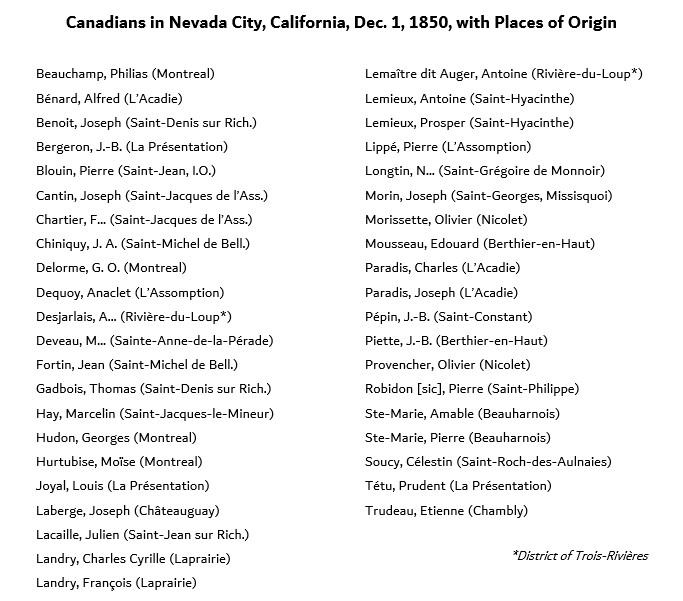

In November 1850, one man wrote from Logtown, about 15 miles from Mormon Island, “Here we are over 100 Canadians and we will spend the winter together. May God help us.”[15] The next month, 41 emigrants hailing from all parts of Lower Canada held a meeting farther north in Nevada City. After appointing Achille Chiniquy their president, they passed a small number of resolutions with a clear message to friends in Lower Canada: don’t come. However unenviable their circumstances, the expatriated Canadians found solace in their mutual company. Back in Logtown, 2,500 miles from home, emigrants held a modest Christmas dinner. They ate, drank, and sang. They toasted “our friends back home,” “our speedy return home,” and “Canada’s fair sex.” Robert d’Estimauville sang “Oh! I’m a used up man.”[16]

As conditions improved in the following year, d’Estimauville sought to correct misperceptions in the Lower Canadian press and change the narrative once again. While recognizing that those seeking a quick fortune had best stay home, d’Estimauville—who as Robert Desty would become a celebrated jurist—challenged the California-as-Sodom narrative. Schools and churches were springing up and displacing card rooms; families were settling down.[17] He issue a protest again in 1853, this time alongside fellow Canadians, who had to defend their good name when a letter in the Journal de Québec claimed they and other exiles were reduced to the lowest circumstances.[18] This type of defense in the face of Quebec misperceptions of the United States would occupy Franco-American elites for more than a century.

Undoubtedly, the most resilient migrants and those who arrived with an entrepreneurial spirit could, over time, improve their lot. Yet, as California society stabilized, the gilded regions lost their luster and Canadian emigration returned to its former pattern. Charles Chiniquy sought to attract settlers to northeastern Illinois. French-Canadian centers along Lake Champlain and the Hudson River grew quickly. Industrialization in Boston’s broad hinterland exerted a more potent pull on those who would willingly settle for far less romantic but far less deadly pursuits.

Legacies

As is typical in history, there is no perfect measure of the gold rush’s effects in Canada or among French Canadians. Even an assessment of its numerical significance could easily miss the mark. From contemporary press reports on French-Canadian participation in the gold rush, one would likely collect several hundred names, far from a full or representative sample. The U.S. census of 1850 states that 834 natives of British America were then living in California. That figure is surely a rough approximation in light of the constant flow of people in and out and between different regions of the state. By 1860, there were over 5,000 residents originating from the British American colonies. These snapshots, in which English Canadians were likely always the majority, do not include people who cycled through between census dates.[19]

Whatever the number of French Canadians who emigrated, their mark on California outlived the height of the gold rush. A small community in San Francisco held a Saint-Jean-Baptiste celebration in the immediate aftermath of the U.S. Civil War. Victor Beaudry moved to Los Angeles where he conducted business with his brother Prudent, a future mayor of the city. Another native of Lower Canada, Damien Marchesseault, served in the same office.[20] The region may also have served as a springboard to even farther locales. In 1858, Frenchmen were reported to be leaving California and traveling to the Fraser Valley of British Columbia where another gold rush was under way. Joseph Rassette planned to build a hotel on Bellingham Bay, near the Canada–U.S. border.[21]

We also have to account for the ripples of Forty-Niners’ decisions in their home communities (beyond the loss of cold, hard cash and the loss of life). These were explorers who relayed valuable information about the Great Republic and gained cultural capital that could serve them in the U.S. Northeast. That one of the first sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste on American soil appeared in New York City in 1850 may be a practical result of the heavy flow of Canadians who were passing through on their way to California or, unexpectedly, choosing to stay.[22]

The gold rush also reminds us that we have long underestimated the extent of French-Canadian mobility between the demise of the fur trade and the U.S. Civil War, both in terms of numbers and geographical reach. Continued study of migration patterns in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s may lead us to surprising discoveries. It may also help us find ways of integrating transnational stories in national narratives that often lead us to compartmentalize past and present experiences. A carpenter’s fortuitous find in 1848 transformed the United States. Countless are the French-Canadian lives that were touched, and just as theirs is an American story, so American history bears the indelible mark of the Canadian presence.

Further Reading

- Aubin, Georges, Les Québécois et la soif de l’or en Californie (2022)

- Brettell, Caroline, Following Father Chiniquy: Immigration, Religious Schism, and Social Change in Nineteenth-Century Illinois (2015)

- Foucrier, Annick, “Français et Canadiens français en Californie,” La francophonie nord-américaine (2013)

- Limerick, Patricia Nelson, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (1987)

- Patorni, François-Marie, The French in New Mexico: Four centuries of Exploration, Adventure, and Influence (2020)

- Roy, Alain, “Sur la piste de Santa Fe, 1721-1880,” La francophonie nord-américaine (2013)

[1] Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Assembly, Appointed to Inquire into the Causes and Importance of the Emigration Which Takes Place Annually, from Lower Canada to the United States (Montreal: Rollo Campbell, 1849).

[2] Quebec Gazette, March 28, 1849.

[3] L’Avenir, July 31, 1849; Kevin Abing, “Directors of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions: 1. Reverend John Baptiste Abraham Brouillet, 1874-1884,” Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, 1994, online, accessed December 11, 2021.

[4] L’Avenir, September 29, 1849. Items from L’Avenir are all drawn from the second edition of the newspaper when available.

[5] L’Avenir, November 23, 1849.

[6] L’Avenir, October 19, 1849 and October 26, 1849; Journal de Québec, March 1, 1851.

[7] L’Avenir, November 16, 1849, November 23, 1849, and November 30, 1849.

[8] La Minerve, February 4, 1850.

[9] La Minerve, December 3, 1849.

[10] Journal de Québec, June 8, 1850.

[11] Gabriel Marchand to Félix-Gabriel Marchand, June 22, 1850 and July 14, 1850, Fonds Félix-Gabriel Marchand, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, P174, S2,P153 and P174,S2,P155. If the oceanic journey was preferable to the overland one, this was no assurance of a smooth and speedy voyage. Victor Beaudry stated that the Rory O’Moore had taken 167 days—more than five months—to reach California from Quebec. See L’Avenir, June 15, 1850.

[12] L’Avenir, July 19, 1850, August 2, 1850, and October 12, 1850. An equally fascinating travel account from Louis Beauchamp, who depicted the realities of the Panamanian isthmus, appeared in L’Avenir, January 25, 1850.

[13] L’Avenir, July 19, 1850.

[14] L’Avenir, October 12, 1850; La Minerve, July 4, 1857. In an interesting twist, it appears Robillard and Rassette had once been business partners. See La Minerve, August 10, 1843.

[15] Journal de Québec, March 1, 1851. The French Canadians’ presence may have given nearby Frenchtown, California, its name. More research is required here.

[16] Le Canadien, February 21, 1851 and March 7, 1851.

[17] Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, October 17, 1851. See, on Desty’s later career, Patrick Lacroix, “American and French: Robert Desty (1827-1895),” Parts I and II, Query the Past, 2019, online, accessed December 11, 2021.

[18] Journal de Québec, February 17, 1853; Montreal Herald, June 17, 1853.

[19] It is possible that some French Canadians were, in 1850, counted among the 1,546 persons listed as France-born. See Table XV: Nativities of the Population of the United States, Seventh Census of the United States: 1850 – An Appendix […] (Washington: Robert Armstrong, 1853), xxxvi; State of California, Table No. 5 – Nativities of Population, Population of the United States in 1860; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), 34. According to one estimate, French-Canadian soldiers in the Mexican War represented 19 percent of British North American enlistments, or nearly 300 individuals. Contextual information suggests that involvement in the California gold rush would have been much greater. See Lacroix, “Canadian-Born Soldiers in the Mexican-American War (1846-48): An Opportunity for Migration Studies,” International Journal of Canadian Studies (2020).

[20] Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1865 (1st ed.). C. C. de Vere’s blog on Los Angeles’s French and French-Canadian history, Frenchtown Confidential, is a particularly helpful resource on Marchesseault, Beaudry, and entrepreneur “Crazy Rémi” Nadeau.

[21] French Canadians also looked beyond the oceans. In 1852, different groups left New York City like their Forty-Niner predecessors, but those who boarded the Ascutna and the Ocean Eagle were going to Australia. Many of them were from a large ring of parishes around Trois-Rivières. See L’Avenir, October 13, 1852; The Age [Melbourne, Australia], August 13, 1858.

[22] Jules Jehin de Prume, Les Canadiens-Français à New-York: Historique de la Colonie Canadienne-Française et de la Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de New-York (Montreal: A. P. Pigeon, 1920).

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree