Frank Foster wasn’t a nobody, but he was no Colonel Wright.

In other words, Franco-Americans could with reason object to the disparaging remarks written into Carroll Wright’s report on labor conditions in 1881. This was a public report issued by a government agency whose claims were informed by Irish workers rather than Franco-Americans themselves.

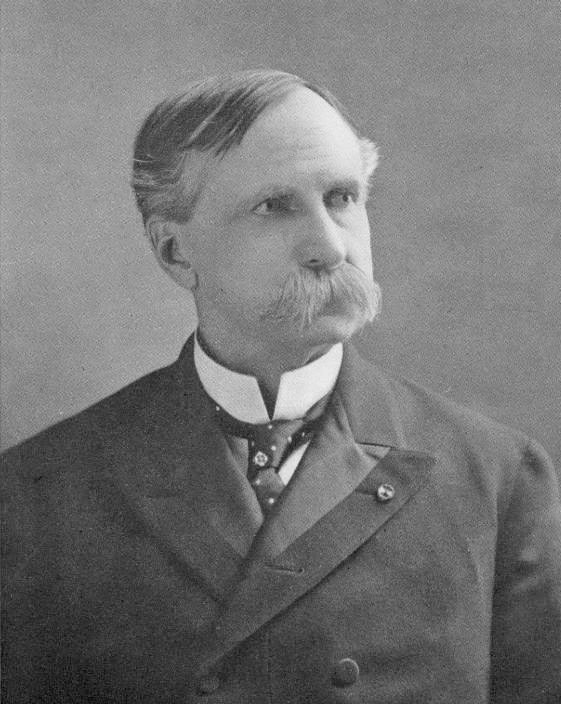

Foster was a printer and a labor leader from Cambridge, Massachusetts and he was presumably entitled to his own views, no matter where he expressed them. Well, it just so happened that he expressed his own prejudice before the U.S. Senate Committee on Education and Labor in Washington, D.C., in early 1883, such that his remarks were given a notable audience. He also happened to quote directly from Wright’s 1881 report, suggesting that this was a continuation of Franco-Americans’ ongoing struggle against the racial slurs used in public forums.

Deemed “the Chinese of the Eastern States” anew, it seemed that Franco-Americans’ vigorous protests in 1881 had been in vain. Franco newspapers were up in arms. Even Quebec’s legislative assembly took note of Foster’s remarks—and took them quite seriously.

This is where Franco-Americans’ struggles again intersect with Prosper Bender. As regular readers may recall, Bender left Quebec City in the fall of 1882. He settled in Boston, where he quickly joined a committee of Brahmins (Peabody, Appleton, et al.) seeking to bring a grand international exposition to the city. Organizers hoped to see this event—initially meant to mimic the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876—take place in Boston in the summer and fall of 1883.

In December 1882, Bender received his close friend Faucher de Saint-Maurice and Etienne-Théodore Pâquet, both Conservative members of the Quebec legislature, and they had the opportunity to inquire for themselves into the exposition’s prospects—and the possible benefits of Quebec’s involvement. The following March, Faucher and Pâquet reported back to the legislature.

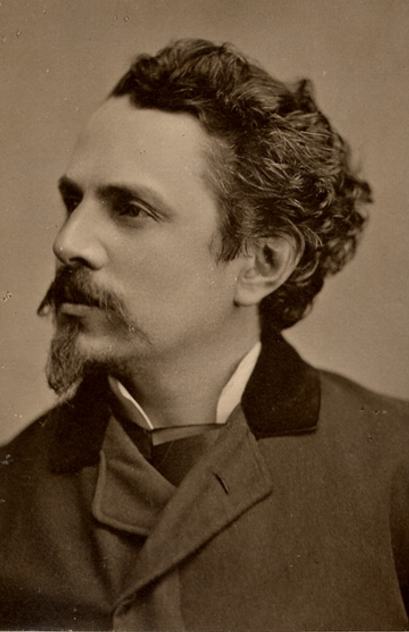

Faucher was as eminent in his day as he has since been forgotten. A school chum of Bender, he then fought with the imperial forces in Mexico in the 1860s—just like Honoré Beaugrand. On his return to Quebec he became a celebrated author, a member of Bender’s salon, and eventually the lead organizer of the French section of the Royal Society of Canada. In 1881, he was elected to the legislative assembly, to which he brought his flair for the perfect word and the dramatic moustaches à l’empereur that captured his personality.

When Faucher stood in the hall of the legislative assembly of Quebec, on March 28, 1883, we may expect that he had a captive and captivated audience.[1] Originally, he had simply planned to share with the chamber correspondence pertaining to Quebec’s participation in Boston’s looming expo. Other events had intervened, however, and actually made the expo question even more pressing. Frank Foster had testified before Congress.

As a preface, Faucher discussed the Wright report and took great pride in the protests that had ensued; Wright had reversed himself and the whole saga had ended with the restoration of French Canadians’ honor. Now Foster had spoken along the same lines.

Luckily, a strong Quebec delegation in Boston, showcasing the resources, advances, and overall well-being of the province might quell once and for all stereotypes about French-Canadian culture. Faucher declared:

Upon seeing the products of our rivers, our forests, our mountains, and our soil, by observing all that makes a man, his home and his international relations, the people of the neighbor country who are strong-hearted and who have a sense of the practical and courageous life will be convinced that we have all that it takes to be a strong, generous, hard-working, moral, and proud nation.

How can they compare the morality of the descendants of New France’s hardy settlers to that of the Chinese in California! And to say that our morals are of a lower standard—that French Canadians’ only purpose in the United States is to subtract as much money as possible from that country! [2]

Faucher provided examples of French Canadians’ service for the Union in the U.S. Civil War; he alluded to their permanent settlements on American soil. He shared similar objections passed by the Franco communities of Worcester, Ware, East Douglas, and New Bedford in Massachusetts; Manville in Rhode Island; and Grosvenordale and Putnam, Connecticut. Pâquet subsequently cited complimentary words from the Boston Herald and the protests of Le Travailleur, Le Messager, and the Courrier des Etats-Unis.

In closing, Faucher argued,

Mr. Speaker: May the unanimous applause that has erupted in this chamber echo through the United States—everywhere a French-Canadian heart beats! May it remind the exiles in our great extended family that, amid our political divisions, we do not forget them. Their joys are our joys; their sorrows are our sorrows; their honor is our honor.

One discordant note through the legislative back-and-forth was struck by the former provincial premier Joly de Lotbinière. The Liberal leader stated that most everyone who went to the U.S. hoped to come back to Quebec. They went south, it seemed, to work, earn an appreciable amount of money, and settle back home. By 1883, a time when this was not wishful thinking was coming to an end. In a sense, it was quite at odds with what Franco-Americans had told Wright regarding their nascent communities—and seemed to confirm Foster’s line of thinking on the transience of French-Canadian life in the U.S. Northeast.

At last, the young premier, Joseph-Alfred Mousseau, denounced Foster and pledged to weigh on the federal government to commit Canada to the Boston event. Ultimately, the expo did proceed as planned, opening in early September 1883, with Canada and Quebec duly represented.

Throughout its history, Quebec’s legislative assembly has regularly risen out of typical sausage making to respond, with near-unanimity, to perceived slights to the honor of French Canadians. The proceedings of March 28, 1883 were even then seen to be of great significance—meriting their publication separately from the regular journals of parliament. We might see in all of this a rehearsal for the outrage bubbling up in the wake of the Riel affair, in 1885-1886.

But, of course, outrage and denunciations come easily. Effective policymaking is another matter entirely. The response of Franco-American communities and the legislative assembly alike conceal the great ambivalence of Quebec leaders towards the emigrants and even greater ambiguity in their policies.

In this greater scheme of things, Foster may indeed have been a nobody.

Sources

The fascinating and extremely lengthy report of the U.S. Senate Committee on Education and Labor is available in distinct parts on Archive.org and HathiTrust.org.

~ ~ ~

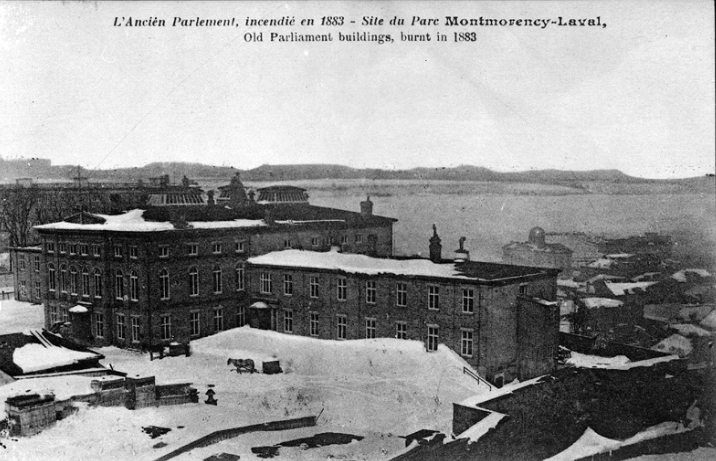

[1] This was not the building that currently houses the National Assembly, which was then under construction. The representatives were provisionally meeting in a nearby hall. That hall went up in flames three weeks after Faucher’s address, forcing the elected officials into Quebec City’s half-completed Parlement.

[2] Many, many parts of the pamphlet issued following this legislative session were extremely defamatory of the Chinese, hinting at the racial blind spots in French Canadians’ thinking.

Leave a Reply