We continue to see online posts and comments about the Patriot invasion and occupation of Quebec in 1775-1776. The subject has become something of a niche parlor game for Quebec history buffs. Some people are quick to opine on the merits of British rule and whether French Canadians in the St. Lawrence River valley might have fared better as the fourteenth state.

Though the events took place nearly 250 years ago, this is not an entirely sterile debate, for it helps us ponder causes and effects, the political culture that developed on each side of the border, and the conditions that molded the experiences of white minority groups in the United States and in Canada. On the other hand, some of these questions seem futile when placed in the context of that which ordinary people lived through, often as bystanders caught up in circumstances whose outcome was inscrutable. They could not know whether the British or the Continentals would prevail—or that both could prevail in their own way—and Canadiens on both sides of the conflict suffered for that.

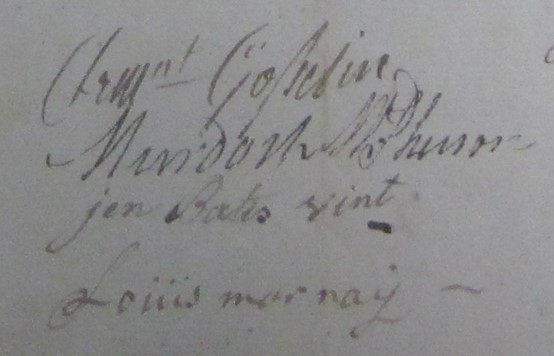

In Quebec, the war was quickly over—though no one could know that for certain at the time. Elsewhere, it lasted eight years, to say nothing of the difficult aftermath. Some exiled French Canadians continued to live on army rations, essentially as refugees, for four years after the Treaty of Paris. It is likely that some went twelve years (at the very least) without seeing their native land. War injuries and illness (as with Clément Gosselin), poverty, uncertainty, estrangement from friends and kin, backbreaking work—this was just the tip of the iceberg. What did liberty and independence truly mean when such were the outcomes of the war?

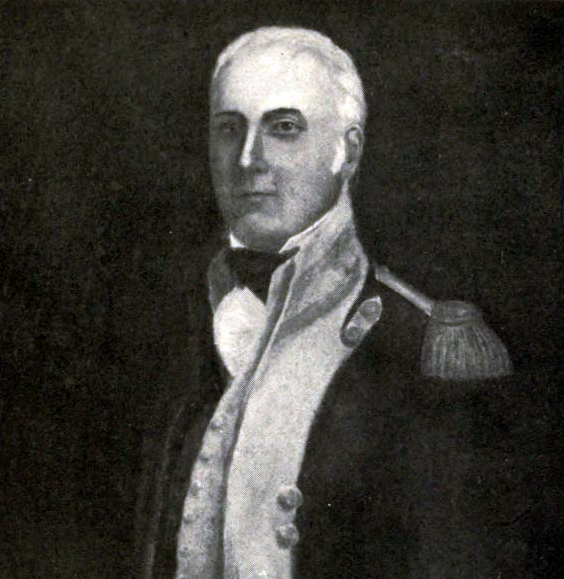

Those personal stories survive in part in the Kent-Delord Collection at SUNY–Plattsburgh. The papers of Benjamin Mooers (1758-1838) are a cornerstone of that collection. Mooers served with the Continental Army during the War of Independence. His uncle, Moses Hazen, led a regiment of exiled Canadian soldiers. After the war, as Hazen became ill, Mooers was entrusted with his affairs and became an advocate for the former officers and soldiers, many of whom awaited a pension or an official title to land in upstate New York.

The following arrangement was fairly typical:

I John Gayney a Refugee from Canada do Constitute and Appoint Benjamin Mooers Gentleman of the State of New York my Attorney in all causes Real personall or mixed moved or to be moved for me or against me, In my name to appear pleas and persue to finall judgment Execution and sattisfaction, with full power of substitution –

witness my hand and seal this sixteenth day of Sept. 1786 –

John Gayney Mark [X]

Signed Sealed and Delivd in the presence of –

Jon Batis Vinet [KD 66.7e 6.8]

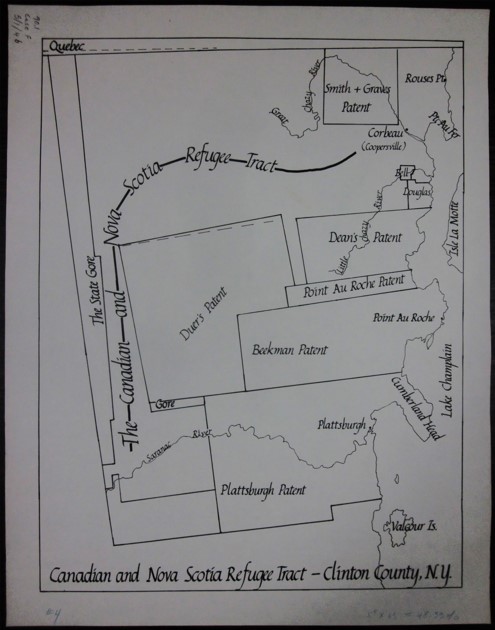

Most claims and power-of-attorney agreements were specifically about land. At the end of the War of Independence, though states might have made small provisions for their soldiers, Congress had no funds with which to compensate veterans of the Continental Army, for which it was responsible. Canadian soldiers pleaded for support; they faced not the intransigeance of authorities but an empty treasury. They received rations and, through the good will of New York State, an occasionally comical amount of land that many of them would never see. Desperate for specie, they sought to sell remote blocks of land that had yet to be surveyed. They were quite simply land rich and cash poor and it made sense to appoint Mooers to represent them as they secured a proper title—and then aimed to quickly sell it.

So it was with Charles Cloutier, originally of Saint-Pierre-du-Sud, District of Quebec, who joined the rebels during the occupation of 1775-1776. According to Gaston Deschênes’ research, Cloutier left the Lake Champlain region between 1787 and 1790 and eventually lived in Saratoga. Mooers’ papers point to a more specific date and highlight the perennial land issue:

Know all men by these Presents that I Charles Cloutier, for divers Goods Causes me there unto moving Have nominated, and Appointed, and do By these Presents nominate and Appoint my trusty Friend Murdock McPherson my true and Lawfull attorney In all causes real, Personal + mixt, to be moved for me or Against me, For him to Draw all dues and Patents Necessary In my name for the further security of Five hundred Acres of Land Granted, sold and Conveyed to me (as shows the above writing) by Joseph Chartier, which Lands were Granted to him as a soldier in the Continental armies and a Refugee from Canada [By the state of New York], for the said Murdock McPherson to Bargain and Convey the said Land to any Person or Persons As he shall think Proper, and to issue deeds and patents in my name In as ample a manner as I my self Could do was I Personally Personally [sic] Present, and to make use of my name and sign as often as need will require Either in Getting the Patents or issuing of them, and all that he shall do will be accepted, as well done By me, the whole Expences and Costs to be Paid out of the said Lands, As Witness my hand this Eight Day of August one thousand seven hundred and Eighty Eight At the little river Chazy.

Charles [his X mark] Cloutier

Signed and Delivered

In Presence of

Charles Caronsel[?]

Clemnt Gosselin [KD 66.7e 6.14]

McPherson transferred this “written instrument” to Mooers the following year.

In some cases, the large tracts of land became a burden. In 1797, “Batiste La Floure and Catherine La Floure his wife of the Parish of St Marks in the province of Lower Canada” (on the Richelieu River) surrendered their land and any claim to it to Chauncey Fitch for $100. Catherine had inherited the parcel from her brother, Sgt. “Michael Myzon,” a refugee.

A year before the battle of Yorktown, while the outcome of the conflict was as uncertain as ever, George Washington had issued his own plea to Congress on behalf of the exiled Canadians:

[B]oth justice and humanity make it infinitely to be desired, it were in our power to make some better provision for persons, who have left their own country and involved themselves in every kind of distress in compliance with our invitations. There have been of late frequent representations to me of their sufferings; I am persuaded Congress will do every thing their means will permit for the relief of these unhappy people. (November 1, 1780)

That call for relief may as well have come a decade later, with Washington now president, for distress and sufferings had hardly lifted in the intervening time. The only difference was land—land that may as well have been fictitious.

The Canadian soldiers’ transnational story fits neatly in an American “national” narrative that finds space for the postwar tumult of Shays’ Rebellion. At the same time, the record of transactions and contracts in the Kent-Delord Collection speaks to the unfortunate circumstances of families that had won the war but lost the peace. The records humanize them and take us beyond “macro” political debates. What had the war wrought? Beneath the story of a fractured continent, we find hundreds and thousands of fractured lives.

Further Reading

Quebec parish records are also invaluable in assessing and understanding the lives of the refugee soldiers and their families. On U.S. soil, they arguably created the first Little Canada. For more on their wartime experience, see Holly Mayer’s Congress’s Own.

I’m so glad to find the history you have provided ! My paternal WELCH genealogy I have studied for years ties into much of what I see in your information. It brings me from early MA across America, in Nova Scotia, etc to the place of my birth in Gratiot County Michigan in 1948. Ancestors served in N.S. during the French and Indian War, the Acadian expulsion, a land grants there in 1761, down into VT and N.E. NY (Clinton County). In western NY/NE OH/MI I find among others, Dutch and French names buried in the cemeteries where my ancestors are buried. For the French in particular the names of Ladeu and LaBounty have interested me. Ladue, Ladow, Labonte along with Moses Hazen, Benjamin Mooers, Clement Goselin, Antoine Paulin(t), William Beaumont and many others are listed in the early censuses with my Welch ancestors,James Welch specifically (sometimeswritten Welsh). There was a Hazen Welch I want to believe was named after Moses Hazen ! Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak MI is where my son was born. My investigation finds that Beaumont Hospital was named for THE William Beaumont in the census with my 5th great grandfather (my belief). Beaumont experimented with digestion of food. The Newcomb family is connected to my family in Michigan. Too much to tell ! But I’m excited to read so much I’m finding on your site and I deeply appreciate your efforts. Thank you !

Thank you for reading, Kathy! What a journey your ancestors had! I hope you enjoy clicking through the site; I have several other posts on the early French-Canadian settlements of far upstate New York. Best of luck in your on-going research.