For generations, it was common to hear the most fatalistic in Quebec claim, “on est né pour un p’tit pain.” In other words, French Canadians were to settle for a simple life—without wealth or status—built around moral virtues.

As in most things in Quebec, it is possible to read the influence of British conquest and Catholic power into this. Perhaps, too, this feeling stemmed from systemic poverty and limited opportunities in certain communities. Like all myths, this view of “providential modesty” is easily falsified, but it nevertheless holds explanatory weight. It certainly helped to justify, and later explain, new ambitions that were realized during the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s.

Because of the duration and geographical extent of the migration from Quebec, we would be hard-pressed to identify such a transformational moment for all Franco-Americans—at least a moment different from other watershed events experienced by all Americans. South of the border, in the shadow of hollowed out textile mills, the myth of perpetual modesty could endure.

Yet, there is more to Franco-Americans’ story than the mere absence of a Quiet Revolution, or some like event.

Quebec was a majority French, Catholic society with its own cultural institutions, increasingly master of its fate as early as the 1860s. The Little Canadas, while they may have been equally French and Catholic, with their own institutions, bathed in a cultural mainstream that could prove particularly hostile. Historians must acknowledge marginalization and discrimination—the very real pain, struggles, and humiliation felt by many Franco-American families. Faith, language, and national origin could be barriers to social advancement, with wealth and status seemingly accruing only to very exceptional individuals. The Francos of the U.S. Northeast could feel especially justified in thinking that they were “né pour un p’tit pain.”

For nearly all immigrant groups, there is, after all, profound tension between the preservation of one’s culture and socioeconomic ascent. The disappearance of the Little Canadas owed to mill shutdowns, but also to rising incomes and new opportunities that enabled families to move out of city centers—as much a cause as a result of acculturation. Naturally, then, historical narratives that focus on culture offer a story of discrimination, defeat, decline, and disappearance. Unable to find a Franco-American Quiet Revolution on which history would turn, researchers have overwhelmingly preferred this model. They have drawn attention a string of religious conflicts; the relocation of textile factories outside of the Northeast; the inescapable forces of the melting pot and suburbanization; loss of newspapers and organizations; and the closure of schools and parishes. And they have concluded, in not so many words, that Franco-American success must be a contradiction in terms.

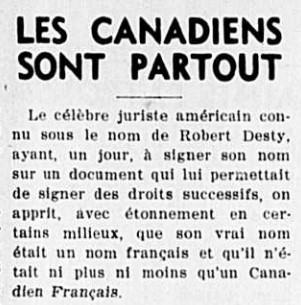

There is, however, another side to the story that still does justice to the facts. Just as the Quiet Revolution was a profound act of collective agency, we must recognize the individual agency of Franco-Americans. There were cultural barriers constraining their agency, but to portray generations of Francos as victims, rather than partial agents of their fate, does them a profound disservice. Such recognition, to begin with, may be a sensible way of reorienting historical narratives.

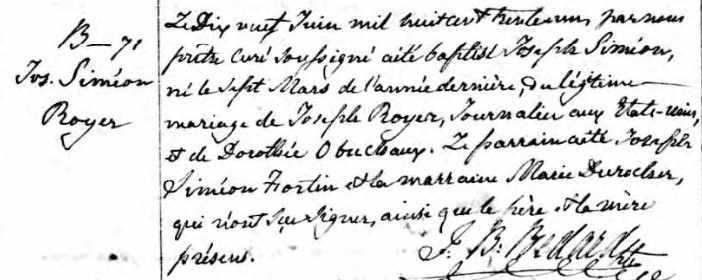

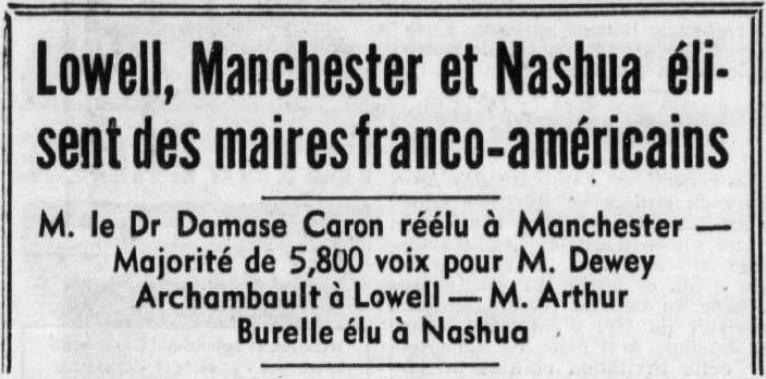

However desperate the migrants may have been, the decision to move to the United States, especially in early times, was a profound act of initiative and empowerment. So, then, was the building of distinct institutions—and voting for Franco-American candidates in local and state elections.

Franco-Americans eagerly attended baseball games and watched Hollywood movies. Many forged alliances with other ethnic groups in civic organizations, the armed forces, politics, labor unions… and matrimonial unions. They sought to offer the next generation a better life—and moving up often meant moving out.

In many respects, Franco-Americans sought to take advantage of the fullest promise of American life and, in the process, became a model minority.

As a historian rather than a community organizer, all I can do is to report my findings while doing justice to my historical actors’ experience. But I think that Franco-Americans, far from seeing the mere, sad tale of gradual disappearance, can afford to recognize the cultural institutions that proved more resilient than those of other ethnic groups; an enduring spirit of exploration and entrepreneurship; political success in many locales across the U.S. Northeast; and a vigorous intellectual and cultural life spanning generations.

Researchers can paint a more comprehensive picture of Franco-American life by including its middle class and those who achieved influence outside of the sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste and conventions nationales. Barry Rodrigue, the author of a biography of industrialist Tom Plant, suggests, in fact, that an alter-narrative of Franco-American history might require new definitions, too:

Franco-Americans are now popularly thought of as French Canadian immigrants to the United States between 1870-1920 who grew up in the ghetto-like petits Canadas of New England industrial towns, worked in mills, spoke French, worshipped in the Roman Catholic faith, voted conservative political agendas and generally did not assimilate into Yankee society until after World War II. The Franco leadership depended on industrial workers and felt that by maintaining the French language and French parishes that [sic] they could promote survivance—the survival of not only Franco-American traditions in the Protestant Yankee world, but their own dominance. In this way, class interest was mingled with ethnicity. However, such a narrow category has become hidebound stereotype that collapses the various waves of French Canadian immigration into one identity. Anyone outside of that experience, such as Tom Plant, simply does not exist. To my mind, such a restrictive definition distorts a rich and varied heritage.

Rodrigue adds, in his conclusion,

By understanding Tom Plant and the early French Canadian migrations to the United States, we can see that many possible paths were open to Franco-Americans. The stereotypical experiences of the petit Canada and survivance were not written in granite. Indeed, such stereotypes are self-fulfilling—those who go beyond it [sic] have been cast into the “outer darkness” and forgotten as Franco-Americans.

By expanding our view of Franco-America, we may view a diverse population beyond a poor working class dedicated to the all-important virtue of cultural and religious preservation. We may find that Franco-Americans were no more born for “un p’tit pain” than other immigrant groups, or white, Anglo-Saxon Americans. Rather than reading into the past “the decline and fall of the Franco-American empire,” we may find a surviving culture of resilience and resourcefulness.

Significantly, we can do all of the above while honoring the tough decisions and tough circumstances of prior generations and while recognizing the considerable odds facing the immigrants and their descendants.

Stay tuned for more on historical narratives as we return to Prosper Bender and the issue of nostalgia in October.

I will be on the road for the next several weeks. I will be speaking on the French-Canadian “Patriots” of the 1770s—arguably the first Franco-Americans—at Fort Ticonderoga’s annual Seminar on the American Revolution. I will also address the American-Canadian Genealogical Society of Manchester, New Hampshire, on Franco-American settlement in upstate New York. I am excited for both and, in both cases, I am extremely grateful for the invitation. The blog will be back with an update and regular posts in October. Until then, please feel free to share questions and comments and meander through this site’s archives. Some recommended reads:

I enjoy the expanded view of the Franco-American experience! It’s refreshing.

Thank you Tim! Glad to hear it!