Stand Up and Be Counted

In the 1970s, the Franco-American world was turned upside down. As old institutions declined, new ones that were better suited to the times took their place.[1] This was still the era of the National Materials Development Center, which contributed significantly to the dissemination of Franco-American research and writing. Assumption College’s French Institute was founded in 1979 and began hosting regular colloquia the following year. Grassroots efforts reflected new enthusiasm for French-Canadian culture—and new ways of expressing it. (For background, please see last week’s post.)

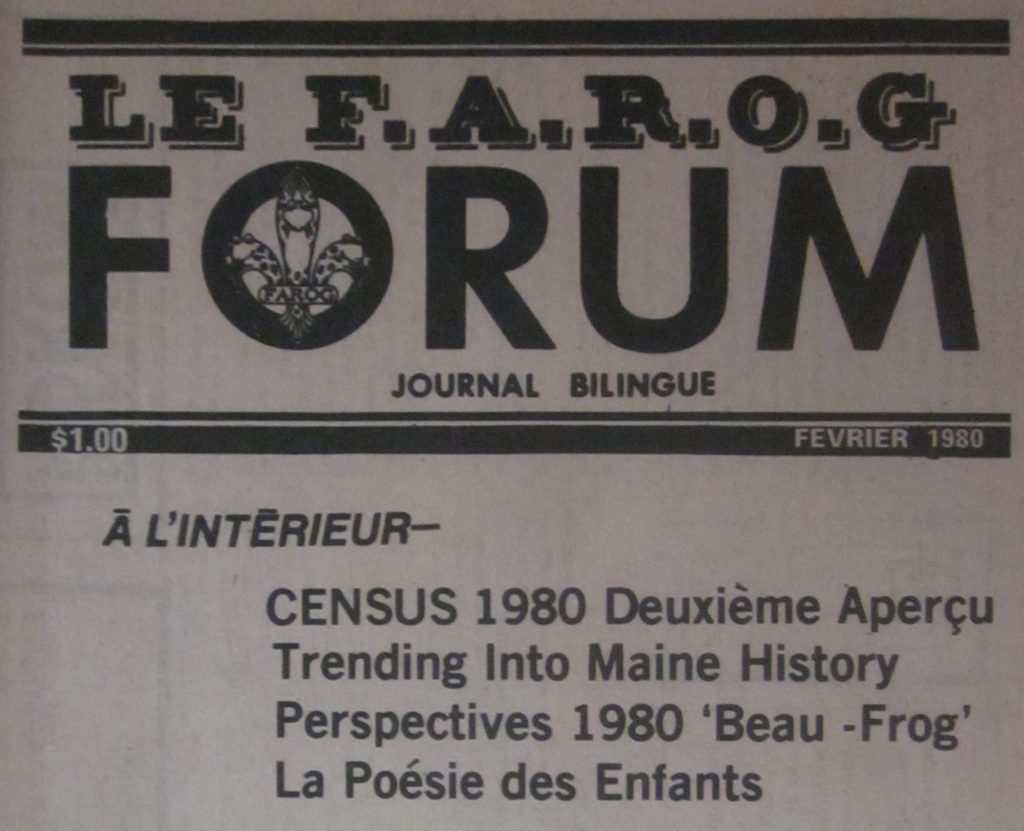

Since 1975, the FAROG Forum had grown into an attractive paper, well-rounded, with a great deal of substance. It had enriched itself with a literary supplement, regular columnists who brought distinct personality to its pages, and the cartoons of Peter “Beau-Frog” Archambault.

Francos in Maine had in fact decisively entered a period of affirmation. A native of the St. John Valley, Lisa Hébert expressed finding new appreciation for her ancestral culture when meeting fellow Franco-Americans at the University of Maine. In April 1980, she wrote,

The Franco-Americans have been ‘in hiding’ long enough. It is time for publicity to come to Franco-Americans. It is time to let the world know about us. We have been considered as ‘other’ too long. By this I mean the many times that Franco-Americans have had to check the word ‘other’ on forms, applications, surveys, etc. to describe themselves. Many ethnic groups are listed, but Franco-Americans come under the group ‘other’. As I grow older, I am becoming more aware of such inequities which kindle certain ill-feeling within me.

Appropriately, this was a census year and it provided people of French-Canadian descent the opportunity to stand up and be counted—to be seen and heard. Madeleine Giguère (the “godmother” of the FAROG youths) insisted on the importance of declaring French ancestry and French-language fluency on the census. In May, in a piece titled “To Be or Not to Be… Buried!” Giguère explained what would come of the census after all of the data had poured in.

This was not the only major event of the year as far as Franco-American life went. Quebeckers went to the polls in May in the first referendum on sovereignty. Tom Vandermeulen provided regular updates on Quebec and Canadian politics until the vote. A significant majority of electors ultimately rejected the Parti Québécois’s campaign for independence. Under “What MacDonald Put Together, Let No Frenchman Put Asunder,” Ludger Duplessis noted the great disappointment at the FAROG office as the results came in. He stated, “We have morally supported Quebec because we know that a strong francophone presence in North America is essential for us to maintain our Franco identity . . . We know Quebec is not our savior, but it certainly is a role model for the feasibility of existing in French in North America, a model for which there are too few.”

Although Université Laval students visited Orono, Francos were far more interested in Quebec than the other way around. Earlier, the Forum had received a letter from Thomas Antil, a Holyoke native now studying in Quebec City. Antil realized just how little Quebec youths knew about Franco-Americans, including their sheer numbers. Older Quebeckers he met were willing to share anecdotes about family connections across the border—but they did not see Francos as a distinct ethnic group, only as “des tantes, des cousins, des grand-oncles, etc.” Many simply assumed that the immigrants from Quebec had all been assimilated over time.

Still, the Quebec government did see opportunities in outreach to Franco-Americans. An emblematic effort was the ActFA (Action pour les Franco-Américains), an umbrella organization founded to coordinate communication between the Department of Intergovernmental Affairs in Quebec City and Francos. A delegation to Quebec included Armand Chartier, Grégoire Chabot, Normand Dubé, Yvon Labbé, Claire Quintal, and coordinator Paul Paré, who were tasked with preparing a report that identified the needs and aspirations of the Franco-American community.

In the States, another campaign was under way, this being a presidential election year. Stephen Duplessis took advantage of political rallies to bring Franco-Americans’ concerns to the attention of Senator Edward Kennedy and Governor Jerry Brown, who were challenging Jimmy Carter in the primaries. In response to Duplessis’ questions, Kennedy shared a few words in French, but offered an unsatisfying response. Brown encouraged Francos to organize in the spirit of “Ask Not.” Duplessis was at least happy to see them both acknowledge Francos’ existence.

Even as the fight for recognition was on-going, there was a great deal of renewed enthusiasm among Franco-Americans, as seen in new organizations and events. Joseph Edward Martin, a physician from the Rumford region, announced the recent creation of the Acadian Heritage Society of the Rumford-Mexico Area. Local residents had felt emboldened to bring attention to this part of the American French community after hearing a talk by a Sister Claire on Acadian history. News of the establishment of a Société canadienne-française du Minnesota trickled eastward.

Meanwhile, a showing of Grégoire Chabot’s “Un Jacques Cartier Errant” at St. Michael’s College in Winooski received high praise. Plans were under way for the fourth annual Franco-American Festival in Lewiston. The University of Maine developed a new major in North American French culture and language. Eloïse Brière was inspired by various efforts in Maine and wished to launch a cultural sensitization campaign at SUNY–Albany. The Albany area had, after all, a rich francophone history, with seven French national parishes in and around the city.

All was not emancipation and satisfaction, however. As in 1975, many Franco-Americans were struggling to come to terms with a difficult past. So it was with Gerard Robichaud, born to a Berlin family and now living in New York City. Robichaud explained, “once upon a time I also felt a quiet shame at the mangled, earthy, if somewhat picturesque language of my p[a]rents. In time I found I shared this shame with many compatriots but in time also, looking back at my parents’ lives, I soon began to say: shame on me!” After seeking to escape his culture, he found himself making a decisive U-turn.

To look back into the past . . . can be for many of us a painful adventure. When our grandparents and parents emigrated from French Canada away from what was for them a future of near poverty in agriculture, they only moved into the misery of factory life, sweatshops really. My own mother died at 45 from a lung disease contracted, I’m sure, from the fumes and dust of a box shop in Rumford, Maine. Some, however, made out better than others. On the whole, it still comes out a quiet saga of daring, courage, survival, and a better future for their children, and all of it, somehow, without food stamps and federal subsidies. Or equal rights legislation.

Contributors to the FAROG Forum did look back in the search for a usable past. Paul Chassé and Paul Paré successively offered glimpses of Maine’s Franco history. The paper carried an address by Gilles Auger to the Lions Club of Sanford about the importance of honoring the Franco past and recognizing French-Canadian culture as part of American culture. Dr. George André Lussier, president of the Comité pour l’avancement du français en Amérique, contributed a piece on the Sentinelle Affair of the 1920s. In addition, certain issues contained oral interviews with older Franco-Americans. Dr. Pierre Aucoin, born to a family of twelve in Grosvernordale, Connecticut, shared his experience as a student at Assumption and, starting in 1937, a physician in Rumford.

In the spring, the FAROG as a whole recognized Franco-American women and highlighted the double challenge standing before them. Josée Vachon wrote about stereotypes concerning Americans in Quebec and those facing French Canadians in Maine. Debbie Gagnon added that “[d]espite the roar of the women’s movement and E.R.A., we’re still trapped into believing that ‘all that is male is good.’ We strive, not to succeed as women, but to succeed on men’s terms.”

Amidst it all, the Forum remained a pluralistic platform and a means of openly expressing the realities of Franco-American life. As it entered the 1980s, the paper received high praise from French Studies scholar Gérard J. Brault—hinting at the achievements of the prior five years:

It would be misleading, of course, to suggest that all’s right with our little Franco-American world, yet one cannot help feeling encouraged by such meetings [as a recent one at Assumption College] and by the banquet celebrating Assumption’s Seventy-Fifth Anniversary held the same evening. At both gatherings, one sensed a great diversity of perceptions of our heritage but one also felt a shared pride in what has been and what is being achieved by the Franco-Americans of New England. What struck me most was the extent of the informal networks that bind us together.

But I did want to tell you, too, how useful FAROG Forum has become for us all. It keeps us informed about what is going on in Franco-Américanie. True to its name, it offers a forum for discussion of current issues. It’s fun to read because of its lively and unaffected style. And, above all, it helps us keep matters in perspective.

Next week: Le Forum in 1988: “Making Connections”

[1] A Forum correspondent from Belgium noted the passing of an era, in 1980, by paying tribute to editor Wilfrid Beaulieu, who passed away shortly after shuttering his Travailleur.

Leave a Reply