As we’ve previously seen on this blog, nineteenth-century government reports contain abundant information about French-Canadian emigration. Legislative committees studied the issue in 1849 and again eight years later. Emigration was also a matter of debate in the halls of Quebec’s provincial legislature after 1867.

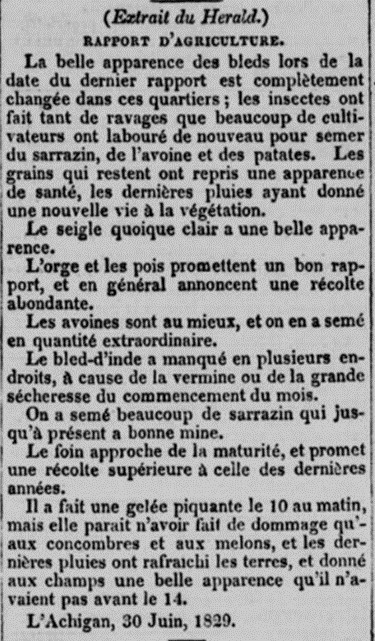

Studies and commentaries commissioned (or received) by the contemporary Canadian press are equally valuable sources. Such articles put forth a wider array of perspectives, explanations, and solutions with regard to emigration than we find in formal government reports. Yet, impressively few scholars have focused specifically on agricultural correspondence—articles about the state of farming in the different districts of Lower Canada. This is a surprising omission, for, if we are to say that emigration to the United States resulted from an agricultural crisis, this rich body of observations should have its place in our discussions.

Admittedly, there has been significant scholarship about the possible agricultural crisis that shook, or might have shaken, Lower Canada prior to the 1850s. Setting aside the finer points of this historical “inside baseball,” the main lines of the debate are as follows:

From his perusal of surviving commercial records, Quebec historian Fernand Ouellet argued in the 1960s that Lower Canadian wheat exports had collapsed dramatically in the first decade of the nineteenth century. This economic downturn did not owe to falling demand in Britain, Ouellet argued. Rather, the colony’s output dropped due to the expansion of agriculture in less fertile regions and to farmers’ conservative practices. Canadian families failed, it seemed, to address soil exhaustion and to improve productivity in older areas of settlement.

Other historians were quick to challenge Ouellet’s interpretation of the data. Gilles Paquet and Jean-Pierre Wallot argued that varying imperial demand molded the level of exports. In response to international market pressures, French Canadians adapted. They developed and refined techniques best suited to their difficult environmental conditions. Paquet and Wallot also studied price indices and parish revenue and concluded that the fortunes of farming families did not, in fact, decline in the early years of the nineteenth century. These authors turned away from the premise of a conservative mentalité among the habitants. French Canadians were willing to modernize; it is this forward-looking approach that enabled them to traverse, at little cost, market fluctuations and that put them at loggerheads with the British regime under Governor Craig.

Ouellet was not persuaded. We might prefer to cast our ancestors as modernizers, but, to Ouellet’s point, subsistence agriculture (then and now) is a field especially averse to innovation, due to the high costs and high risks it entails. In any event, the historical positions staked in the 1960s and 1970s have since blurred as a result of novel research that has exposed regional differences and brought new sources into the conversation. Allan Greer identified no net decline in people’s living conditions in the first third of the century, but posited that demographic growth would have limited opportunities available to the next generation. Christian Dessureault has highlighted the very different circumstances that farming families could experience even within a single seigneurie. Bruno Ramirez has carried the story farther in time and looked at the splintering of the agricultural class according to its means; some families could adapt, others drifted towards poverty and had to resort to other pursuits.[1] Scholars have also looked into the role of seigneurial dues and studied the issue from the angle of an integrated agroforestry sector. The effects of pests like the wheat midge remain little known and little explored.

This extremely long preface is meant to contextualize a body of sources that can move the debate forward and help us make sense of agricultural factors in outmigration. Agricultural reports published in the press by nongovernmental observers provide a helpful glimpse into the practices and climatic conditions that molded farmers’ circumstances from one season to the next. Quantitative evidence may offer the pretense of scientific certainty; qualitative reports, for their part, provide explanations from well-informed individuals that can set trends in their full context.

Take, for example, the following report from the Montreal area in the dreadful (and infamous) year of 1816:

Since the first week [of September], there has been a continued drought to the end of the month, the weather has generally been very hazy, attended with cold winds; on the 11th a severe frost was experienced. The 19th and 20th were extremely warm; the 26th, 27th, and 28th, the frost was so severe, as to complete the destruction of the Potatoe haulm, which escaped that of the 11th. The effect of such unseasonable weather, has been particularly felt by all the standing crops, which were in a backward state, requiring warmth and rain, to bring them to maturity.

The author went on to present the state of different crops across the District of Montreal. The educated observers who contributed these reports seldom stuck to a descriptive and disinterested style, however. They shared in farmers’ disappointments with weather conditions and regularly shared “best practices.” From 1822:

Some farmers in this neighbourhood [the District of Quebec], being fearful of a dry season after the present rains, have completed the preparatory labour for turnip sowing, in order to take advantage of the moisture now in the ground . . . There is probably no remedy [to the proliferation of weeds] but a proper rotation of crops . . . We have seen on a farm under this rotation, a field of very poor land which was covered with Sorrel, Marguerites & other noxious weeds, & which has had no manure but with the Drill Crop[2] of 1820, that will yield this year at the rate of 300 bundles per arpent of clean Timothy and Clover Hay.

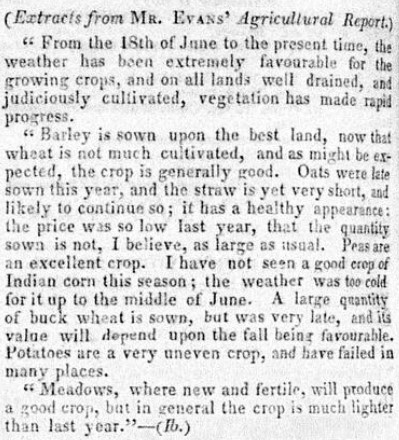

The most reliable contributor on agricultural matters was the Irish-born William Evans, who benefitted from access to foreign information—agronomy being much more developed in Britain. Evans operated a large experimental farm just outside of Montreal. He could afford to work by trial and error when many Canadiens were not so fortunate. He advocated for the expansion of cattle herds to ease access to fertilizer, diversify food sources, and take advantage of demand in Lower Canada’s towns. In addition, the building of local breweries would reduce the cost of transporting grain to faraway markets, ensure that barley surpluses were fully utilized, and raise farmers’ income.

Evans proved to be a regular—and, for historians, valuable—chronicler of Lower Canada’s agricultural woes from the 1830s onward. In the prior decade, farmers had had to contend with invasions of grasshoppers and the wheat rust. Fly larvae began decimating growing wheat stalks consistently from 1832. In 1835, Evans articulated the likely failure of the wheat crop in the District of Montreal. The continued wheat crisis would entail a change in diet, he explained. He recommended mixing barley flour with the wheat to address the shortage.

That crisis grew worse before lifting. In the summer of 1836, the Vindicator reported on conditions around Quebec City:

[N]ever in the memory of the oldest inhabitants have the prospects of the harvest been so unfavorable in this vicinity. It behoves the poorer classes to exert all their industry and practise the greatest economy and foresight, to provide the necessaries of life for the ensuing winter. It behoves the wealthier classes to remember that they are ‘the stewards of the poor,’ to waste nothing, and be prepared for the calls that will be made on them.

A year later, as the colony hurtled towards insurrection, Evans found that the wheat fly was “as numerous as ever” (as it would be again in 1838 and 1839). He proposed the very risky idea of sowing wheat in the fall or later than usual in the spring, after the short window during which flies laid their eggs. Evans later reversed course: the seed often did not survive a prolonged frost, while a later sowing entailed a shorter growing season. Meanwhile, dry rot in potatoes became exceedingly common, though this, at least, could be prevented by planting the whole potato instead of the seed. Canadians would not be so lucky when, in 1844, a potato blight not unlike Ireland’s again dramatically reduced production. Through the lean years of the 1830s and 1840s, the agricultural class had little choice but to turn to oats, rye, and peas and hope for ideal growing conditions.[3]

The challenges of this period may have forced families to diversify out of desperation; they did not, however, foster long-term thinking and planning which might have set a new course for Lower Canadian agriculture. Growing competition from other regions of North America—which benefitted from better soils and climates and access to Eastern markets through canals—may also have stunted the agricultural sector. Unable to find outlets for their viable products, Canadian farmers would have been confined to subsistence farming. In the 1840s, Evans would argue that prosperity meant aligning domestic production with the needs of consumers in Quebec City and Montreal, but this could only be a slow transition effected by families of certain means.

* * *

The historical literature on Lower Canada or Quebec’s agricultural troubles is focused almost entirely on the period prior to 1850. Reports of pests, crop failures, and rural impoverishment become much scarcer in the second half of the century—the period when emigration to the United States reached its apex. It is possible to connect and reconcile to these two phenomena in several ways:

- Emigration began prior to the Rebellions and became a large, mass movement around 1840. This movement may have taken on a life of its own, creating chain migration and encouraging more and more young people to seek opportunities abroad, notwithstanding agricultural conditions in their homeland.

- The consequences of successive lean years may have been long-term, creating a cycle of indebtedness and impoverishment that grew over the course of many years. Emigration would have been the solution of last resort.

- Agriculture continued to change in the second half of the nineteenth century. Different activities and the introduction of farm implements may have capped the amount of labor needed in the Lower Canadian countryside.

If these three hypotheses are likely all part of the explanation, the picture is further complicated by non-agricultural factors. The next blog post will fill out the picture by turning to demographic and broader economic factors.

See, as helpful overviews of the debate on agricultural conditions, Alain Laberge, “Crise, malaise et restructuration: l’agriculture bas-canadienne dans tous ses états” (1996) and Peter A. Russell, How Agriculture Made Canada: Farming in the Nineteenth Century (2012). See, on governmental approaches to emigration in the last third of the nineteenth century, my compilations of legislative debates, which respectively cover sessions from 1867 to 1880 and from 1881 to 1900.

[1] This raises the provocative possibility that the conservative well-to-do remained in Quebec while the poor and disaffected—more likely to agitate for change—headed to the United States. Emigration would thus have been an ideological outlet, helping to cement the ascendency of a conservative clerical nationalism in the second half of the nineteenth century.

[2] Presumably, tubers planted in furrows.

[3] This can serve as a continued invitation to study the evolution of Canadian foodways through the nineteenth century. Local wheat production fell—though families turned to flour produced at a lower cost in other parts of the continent. Cattle herds grew. At the end of the century, the provincial government began to actively promote dairy farming. Only later would we witness the rise of a proper agrofood sector and the iconic corn fields in the agricultural belt surrounding Montreal—a commercial crop unmoored from people’s day-to-day diets.

As so often happens, the really good stuff is in the footnotes. Susan Gazaille’s master’s thesis looked at school enrollment in my hometown of Holyoke in 1880 and found that only 30% of Franco-headed households that sent kids to school, sent them to the French school. The others went to public schools or the Irish school. This was partly due to capacity and location, but her thesis suggests that this is evidence that the F-C’s were more concerned with assimilation than survivance. It probably didn’t help that the Quebec-born F-C pastor appeared to be a traditional conservative top-down autocratic leader. It makes sense that F-C’s who emigrated, in part, to escape heavy-handed clerical control resisted it where they found it in New England.

Disclosure – Susan and I were high school friends.

Fascinating! Do you have the title of her thesis?

Education and survivance in Holyoke, Massachusetts ca. 1880 the choices of French-Canadian families.

Here is the link, it’s available as a free pdf. She was able to get a pretty large sample crossreferencing US Census and enrollment data from the schools. Not sure if she did any more historical research – she went into library science and is now the Dean of Libraries at Smith College – Susan Fliss.

https://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/4859

Sounds great – thank you, Dan!