It was half past three on July 5, 1888—well, shortly after half past three, some members of Quebec’s lower house being perennially slow to take their seats. Speaker Marchand turned to the honorable member for the riding of Bellechasse, on his left. Faucher de Saint-Maurice had the floor. So did, vicariously, the Franco-American community. Faucher had, several days earlier, returned from Nashua, New Hampshire, site of the latest national convention of French Canadians in the United States. With him on that excursion had been L.-O. David, a friend who sat on the government benches and who would also address the legislature. They had gone to Nashua as a bipartisan delegation of the Quebec government. The time to report on their findings south of the border had now come.

Since 1867, the Quebec government’s relationship with expatriates had been complicated to say the least. Members of the legislature could not agree on the causes of the French-Canadian diaspora, let alone policies that might keep more residents in the province or help repatriate those abroad. Elected officials worried about the emigration movement that imperiled Quebec’s economic fortunes and diminished its influence within Confederation.[1]

Many refused to see the structural forces causing the province’s mass exodus; instead, they tarred the emigrants with every conceivable vice. These were—supposedly—lazy, self-indulgent individuals who cared nothing for hard work or their country. Not all officials viewed the emigrants through this moral prism. For instance, Félix-Gabriel Marchand, future premier and speaker of the House in 1888, was a steadfast advocate for those whom poverty had driven to the United States. But contempt there nevertheless was in public discourse.

The other factor that colored policy responses was the growing sense that the French-Canadian nation could only “happen” in Quebec. The fates of a culture and a province were increasingly entwined in the work of the provincial government. That was most apparent in domestic colonization schemes, the settlement of Quebec’s outlying areas by French-Canadian farming families. In the 1870s, the government created “colonies” in the Eastern Townships and in the Témiscouata region. It hoped to divert emigration from American industrial centers and entice possible repatriates. The sale of affordable Crown Lands north of the St. Lawrence River might also do the trick. Ultimately, for every person who took advantage of these settlement schemes, ten went to the United States.

The industrial depression of the 1870s raised hopes in Quebec City. By the next decade, however, French Canadians were leaving the St. Lawrence River valley in record numbers. Provincial authorities struggled to remedy the situation and many simply followed Antoine Labelle, the colonizing curé, in his efforts to settle likely (or former) emigrants in the Quebec backcountry.

Then came Mercier.

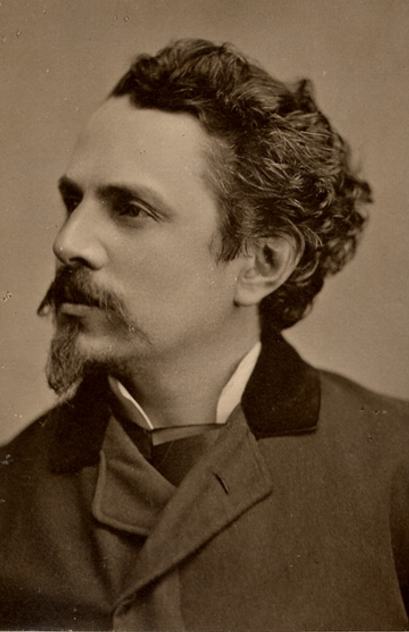

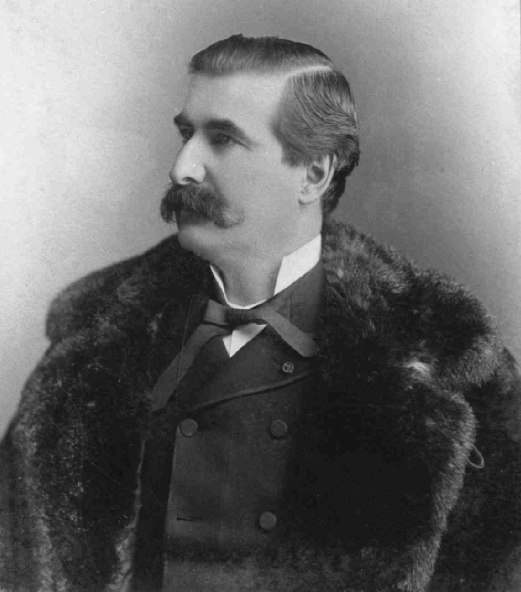

Honoré Mercier, a moderate Liberal, became premier in the wake of the North-West Rebellion, or Resistance. Though leading a nominally bipartisan coalition, Mercier got into hot water early in his time in office. He had expressed reservations about Labelle’s claims; left and right, defenders of the holy apostle of colonization shot back. In the spring of 1888, in the spirit of reconciliation, the premier appointed Labelle to a senior civil service office. To substantiate his interest in the emigration issue, he also appointed Faucher de Saint-Maurice and L.-O. David as goodwill ambassadors to nascent Franco-American communities. The pair might sell repatriation to those who had deserted the homeland and, by reporting back to the legislature, offer guidance to Quebec policymakers.

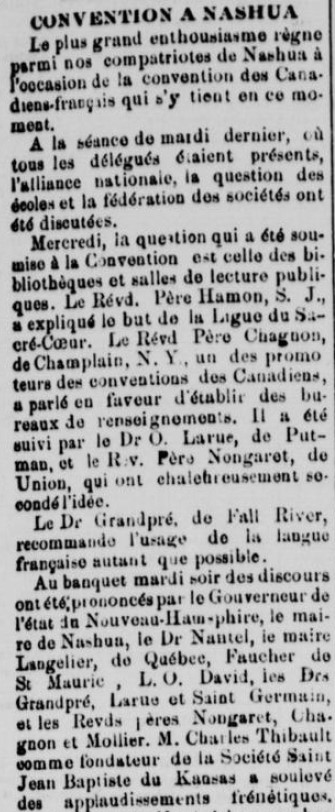

Thus the two legislators went to the national convention in Nashua, which coincided with Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, 1888. The event was a veritable who’s who of the Franco-American world: Major Edmond Mallet of Washington, D.C.; Louis J. Martel of Lewiston; Omer Larue of Putnam, Connecticut; Hugo Dubuque of Fall River; and many other figures of importance. (Dubuque’s remarks in Nashua have previously appeared on this blog.)

Quebec’s political leadership was meeting the cream of Franco society, and not just anywhere. Fourteen years earlier, in efforts to promote repatriation, Quebec elites had organized a giant French-Canadian convention in Montreal. Taking advantage of reduced rail rates, thousands had come back from their American abodes—temporarily. It was very telling that in 1888, Quebec legislators were going south to meet expatriates on their adoptive soil.

They talked the Franco-American talk. On emigration, the language of providentialism—the idea that French Canadians were called by God to expand culturally, cross borders, and conquer new regions for their ancestral faith—was not unknown in Quebec, but it was never a dominant intellectual current. But, in the 1880s and 1890s, Franco-American elites mobilized that rhetoric to assert their legitimacy and gain credibility in the eyes of their compatriots back home; French-Canadian clergy in the Northeast easily folded the ideology of survivance in that sense of a divine mission.

With Major Mallet at his side, before the distinguished Franco delegates in Nashua, Faucher could only exclaim, impressed by the sincerity of his audience, “Our destiny has truly been providential and we can be proud of ourselves!” He then repeated what he had told the legislature before his departure, that “we do not forget [the expatriates]; their happiness is our happiness; their sorrows are our sorrows; their honor is our honor.” The convention members in Nashua were touched by the fraternal spirit at long last extended from the province of their birth.

Within the halls of the legislative assembly, in July, Faucher testified to the strength and resilience of French Canadians in the United States. They were French, but loyal to the land they now inhabited. They deserved the esteem and support of Quebec. Perhaps we should not be surprised by Faucher’s remarks—and not merely because one of his closest friends, our dear Dr. Bender, was now living in Boston. Five years earlier, as a rookie legislator, he had taken the floor of the assembly to denounce the vitriol poured on French Canadians by American labor leaders. But how could French Quebeckers defend the honor of their “race” if they themselves depicted expats as a ragtag rabble? They could only contest the disparaging rhetoric of American nativists by recognizing that emigrants were successfully transplanting Quebec and, in the process, doing their ancestors and their “race” proud.

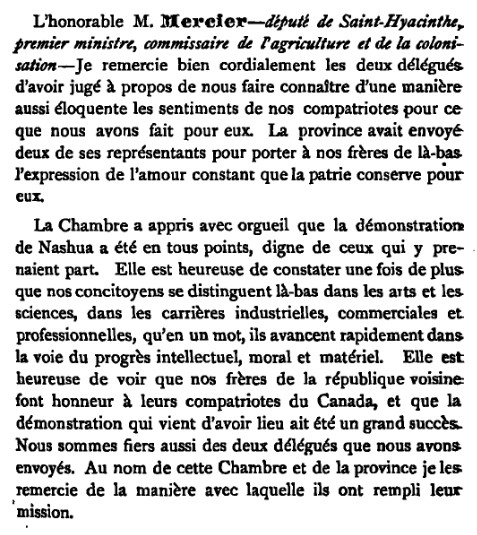

Such was the tenor of Faucher’s remarks. His travel companion shared a similar impression of Franco-Americans—and, as was typical, went further and spoke what Faucher had implied. “While they miss the patrie,” David stated, “I think it’s fair to say that French Canadians in the United States would not want to return to Canada. I mean to say in general…” He lent his support to the colonization movement, but concluded that by the end of the century, millions of French Canadians would, while faithful to their traditions, become loyal American citizens. Mercier, Opposition Leader Louis-Olivier Taillon, and the whole House—by resolution—thanked the two delegates.

After the session of 1888, a substantive change occurred in the legislative assembly’s approach to repatriation. Emigration was little discussed as a distinct issue. Concern about depopulation certainly remained, but often appeared as a specter conveniently waved from Opposition benches. In the 1870s, representatives who spoke ill of the repatriation campaign were likely to be labeled unpatriotic. A few decades later, repatriation was regularly discussed as impractical, expensive, or doomed to fail.

A year after the Nashua convention, a House member from the Eastern Townships argued that it would be to the government’s credit to keep people in Quebec rather than try to bring back those who had left. Liberal James McShane, soon to be elected mayor of Montreal, opposed any further funds for repatriation; “every effort, however generous and patriotic, has been unfruitful, and all of the grants wasted.” It was absurd to lure back expatriates, McShane stated, until opportunities had significantly improved in Quebec.

McShane was back at it in 1890. And the chorus grew. The Liberal member for Verchères (Mr. Lussier) reversed himself in a single parliamentary session, ultimately concluding that government credits only benefitted repatriation agents sent by the government. Now approaching—unbeknownst to all—the final year of his premiership, Mercier shared David’s outlook. Repatriation had become a “cause désespérée.”

By 1895, Quebec had rid itself of all repatriation agents but one. His office—this spoke volumes—was in downtown in Montreal.

Circling back through the decades, we can find numerous points of fracture between Quebec and Franco-Americans. (All are symbolic, but there is still meaning to them.) We might think of 1960, when La Presse discontinued its news column on Franco-Americans, or the gradual break-up of transplanted Quebec—the Little Canadas—from the Second World War onwards. Historian Robert Rumilly argued that a major psychological break occurred around the time of the first conscription crisis.

We should now add Faucher and David’s mission to the list. Their embassy likely had little impact on popular mindsets in Quebec and in the United States, at least in the short term. Yet it made a strong impression in the halls of power and may stand as the definitive death knell of repatriation as a political project. As modern Franco-Americans contemplate a physical return to their northern roots, perhaps they will foster the same spirit of cross-border esteem that marked the Nashua convention. This time, however, dialogue with Quebec will mark not the separation of destinies, but the merging of long-estranged communities.

[1] The structural factors that pushed French Canadians onto U.S. soil are too many and complex to detail here. Still, it should be noted that Lower Canadian agriculture experienced constant adjustment through the nineteenth century. Some historians have fallen in trap of reading Horace Miner’s study of Saint-Denis (Kamouraska County), which dates from the 1930s, back into a more distant past. It is as though the Quebec countryside was unchanging from the fall of New France to the Second World War. That could not be farther from the truth. In the early nineteenth century, the wheat market collapsed and French-Canadian farmers diversified; they turned to hardier but less commercially viable crops like potatoes and barley. Later in the century, expanding commercial networks meant new competition that hindered access to capital. That became an issue as farmers relied on mass-produced goods that they would purchase. Modern refrigeration contributed to the turn to dairy; technological innovation lowered labor needs at a time when the population was still growing exponentially. Finally, it may be more appropriate to speak of an agroforestry sector, with the shocks in the lumber industry preventing men from earning wages that supplemented a farm’s income.

My John F. Kennedy and the Politics of Faith is available from the University Press of Kansas. Consider buying from the publisher or supporting your locally-owned bookstore.

For more on late nineteenth-century providentialism and provincial development projects, see my piece in the winter 2018 issue of The Historian. My compilation of legislative debates on emigration and repatriation in the years after Confederation is available online.

Leave a Reply