See the first installment on important Franco-American documents here.

A Man and His Dream (1909)

Félix Albert had a tale to tell—with some false modesty, his own. In the early twentieth century, after a turbulent life, he had someone, perhaps a local priest, write down his experience as an immigrant and a man of many trades. Albert was a product of the St. Lawrence River valley below Quebec City. In true entrepreneurial fashion, he sought to complement his farm’s income in lumber, in northern Maine. A number of reversals brought the Albert family to the Lowell area in the early 1880s, at the height of the exodus from Quebec.

Albert established a considerable business as a builder—and lost it all in the course of the economic depression of the 1890s. He returned to selling wood. Though their sons achieved some success in life, Albert and his wife seem to have spent their later life in modest circumstances. Their tale says something of the limited opportunities for farmers in Quebec as well as the hopes and risks awaiting them through the migration process. Like Félix, many immigrants set their sights well beyond the textile industry. They relied on the capital of experience they had earned in Canada or in smaller U.S. centers and to build a secure future for themselves and their children.

In a later introduction to the story, historian Frances Early drew well-deserved attention to Albert’s wife, who remains unnamed throughout the tale. It is a telling (but likely unwitting) statement on women’s place in Franco-American history. Her commentary invites us to read between the lines and to consider the challenges faced by the entire household—though Félix all too willingly placed himself front and center.

First-person perspectives from the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries that have been recorded in writing are far too few. Another valuable source for first-person immigrant stories is C. Stewart Doty’s First Franco-Americans (1985), a collection of oral interviews from the Federal Writers’ Project. In this case, the material was filtered by interviewers and must be approached even more critically.

One-Hundred-Percent American (1924)

After the troubled 1880s and the anxious responses to Edouard Hamon’s report, Franco-Americans again experienced the worst edges of U.S. nativism in the wake of the First World War. In order to cement support for an all-out war effort, the federal government whipped up a campaign of intense patriotism that ultimately turned against minority groups.

For the most part, Francos continued to believe in the great American experiment. By the 1920s, despite renewed immigration from Quebec, most had little to no experience whatsoever of Canada. As they had in the prior century, Francos overwhelmingly rejected calls to “repatriate” (a term that was actually nonsensical in most communities).

François-Xavier Belleau, a prominent resident of Lewiston active in Franco cultural circles, had a ready response to both advocates of repatriation and American nativists (including a text that assailed Francos as “Fifty-Fifty Americans”). Belleau was a staunch promoter of naturalization. In an open letter written in the fall of 1924, he argued that French Canadians renounced nothing by becoming citizens of the Great Republic. They could still honor their traditions on U.S. soil, and further rebut claims about their supposed half-hearted commitment to their adoptive country.

March 14, 1906 (BAnQ)

Greater use of the ballot would translate into political influence and the opportunity to challenge stereotypes about these French-speaking Catholics from Quebec. Prefacing his own claims with a Shakespearean “We must be, or not be,” Belleau added, “Let us demolish all of the old prejudices that have hurt us, educate young and old, and seek naturalization in great numbers. We are betraying nothing.”

Although pessimism and disappointment underlay Belleau’s letter, the years had in fact worked in Franco-Americans’ favor. Through the 1920s and 1930s, Francos did find a voice in politics and elected their own to city halls, state legislatures, and the U.S. Congress as well as finding representation in unelected local and state positions. It may even be argued that the rise of the northern Ku Klux Klan in this period had much to do with the arduous ascent of minority groups to centers of power.

A Voice for Franco-American Women (1936)

As noted above, there are gendered blinders to the conventional telling of Franco-American history. Women were just as much makers of a recognizable Franco-America as men, only they faced considerable barriers and did not find their voices properly reflected in the historical narrative. Camille Lessard-Bissonnette’s Canuck, a novel, thus stands out in high relief.

Lessard was a Quebec native who settled in Lewiston, Maine, early in the twentieth century. She worked, as so many other young women, in a textile factory. She was quickly noticed for her literary skill and began writing for French-language newspapers. Beyond her contribution to the cause of women’s suffrage, she would work in other parts of the U.S., contribute to other publications, and eventually pass away in California in 1970. Canuck appeared serially in Le Messager in 1936.

Lessard’s novel is eclectic—part dime novel, roman du terroir, and a uniquely Franco-American creation. It traces the life of a young woman whose early years mirror Lessard’s, though the character experiences the tenements and factories of Lowell, not Lewiston. The tale comes with family conflict that leads the character, Vic (for Victoria), to strike out on her own. After facing heartache, she joins her widowed mother on a Quebec farm—fulfilling the traditional French-Canadian way of life while affirming the possibility of greater female independence. Along the way we catch a realistic glimpse of factory and farm life. Through her struggles, Vic is blessed; her higher hopes are met when wealth literally falls from the sky—a sign of providential action if ever there was one. That enables her to get the prince charming she had met many years before in Lowell.

The novel has tangential sections that almost suggest that the author was struggling to keep up with the serial publication. But Camille Lessard-Bissonnete effectively captured the many tensions inhabiting Franco-American life: between New England and Quebec, between values old and new, between the genders, and between family cohesion and independence.

The Little Canada Is Dead; Long Live the Little Canada (1954)

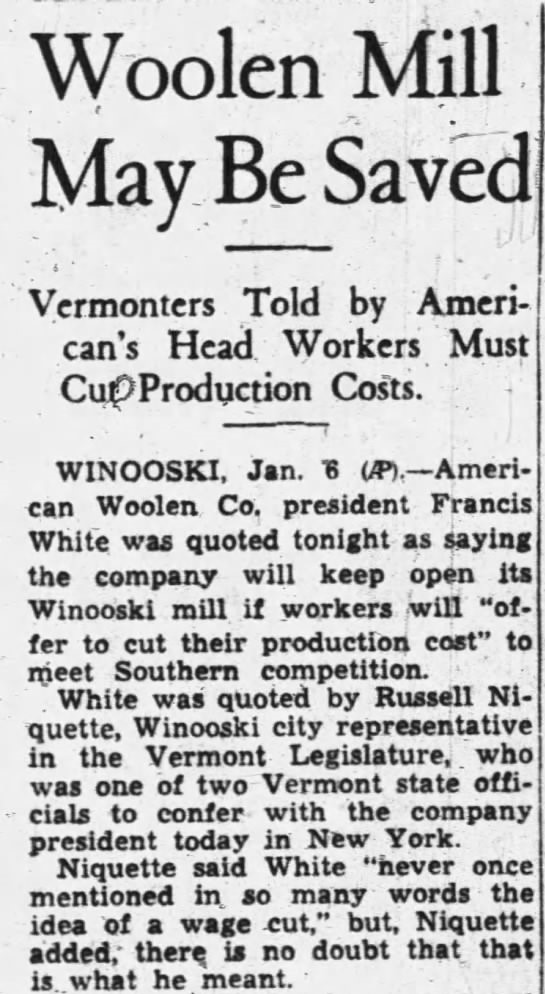

Any number of newspaper reports could do here: the threat of factory closures and their actual demise in the postwar period. Of course, textile mills did not all suddenly end their operations in the 1950s. The process was then decades-old and over the course of that time Franco-Americans had become less dependent on the textile sector.

An AP piece published in the Rutland Daily Herald in January 1954 nevertheless hints at a larger experience. The title, “Woolen Mill May Be Saved,” alluding to the factories in Winooski, Vermont, underscores the glimpses of hope that were ultimately dashed throughout the region. At a meeting in New York City, the president of the American Woolen Company, indicated that the corporation would have to end activities in Winooski and Lawrence, Massachusetts unless production costs met those in the American South. Russell Niquette reported the proceedings back to Vermont; there was no doubt, in his view, that the company would ask workers to take a substantial pay cut to continue production in both locations. They would have to accept a 20-percent cut and relinquish all benefits to match Southern conditions.

In reality, the fate of the Winooski mills was probably already sealed. Production ceased that summer, leaving hundreds unemployed. This specific article did not mention Southern locations explicitly; other pieces noted the consolidation of operations at newer plants—with a cheaper workforce—in Raleigh, North Carolina, and Tifton, Georgia.

This was the passing of an era. The disintegration of the Little Canadas partly due to mill closures in the postwar period has been exaggerated in some ways; this was a long process that affected successive generations differently. Symbolically, however, this was a landmark moment. In decades that followed, Catholic parishes consolidated, French-language newspapers folded, and older organizations ceased their activities. But by no means was this shifting cultural and economic landscape the end of French-Canadian heritage in the Northeast.

The Light of a New Day (1972)

Before Le Forum, which is essential reading for Francos, there was Le Fanal, “The Lantern.”

Published in early summer, 1972, at the University of Maine, this newsletter announced the beginning of a new cultural militancy among Franco-Americans. Soon the young turks in Maine formed the Franco-American Resource Opportunity Group; in time their efforts would produce courses specifically on the Franco experience and lead to the creation of the Franco-American Center. In Le Forum, students—at times irreverent but always profoundly sincere—shared the concerns of their generation, interpreting their heritage and identity through the lens of their unique circumstances.

There was open and frank criticism of the Catholic Church. There was a rejection of the “polished” metropolitan French purveyed by elites. Mental health was discussed. Women’s voices assumed a previously unseen prominence. The Quebec sovereignty movement also occupied an important share of the paper’s news coverage. In short, this was a period of emancipation that set Franco-America on a whole new track as the Maine students’ efforts radiated through the Northeast. No more vaches sacrées.

Over the course of five decades, Le Forum has brought together a wide array of perspectives—from students, scholars, community organizers, everyday people eager to speak to other Francos, and now bloggers, all from different parts of Canada and the United States.

Franco-America always defied easy categories; Le Forum has revealed just how diverse the descendants of French-Canadian immigrants have actually been.

I resisted the temptation of selecting Franco-American documents from the last forty years, since we do not have the same historical distance (or perspective) to adjudicate significance.

Yet we do have really wonderful memoirs and novels; advertising materials, photos, and news stories about local festivals; podcasts; and so forth. What might you choose to represent this recent period? How would you alter this list? Comment below or on social media!

Leave a Reply