Regular readers know what’s coming—the well-worn rant about New York State’s unenviable place in Franco-American studies. Well, this time it comes with data.

Briefly, for context, the major syntheses on the Franco-American experience in the eastern United States all focus explicitly on New England—and even then, large swaths of those six states are hardly acknowledged. We cannot fault authors or editors for the geographical areas they choose; no book is perfectly exhaustive, and studies require boundaries if they are to be coherent and manageable. However, considering the magnitude of French-Canadian immigration to New York and the similarities to the “ethnic” experience in New England, we can only be startled to find a relatively open field of research. We can recognize the existing studies on New York Franco-Americans (and the impressive work done by local historical societies and museums with limited means) while deploring the gap in scholarship between this state and the arc of mill cities in Boston’s hinterland.

Improvements in transportation and communication ensured increasing contact between French Canadians and Americans prior to 1840, when, according to most historians, the great demographic hemorrhage from Lower Canada began in earnest. The Champlain–Richelieu axis was a major commercial artery from the very beginning of the nineteenth century. Even as the Champlain Canal, the Erie Canal, and, later, railways began to alter traffic on this “hydrographic highway,” French-Canadian communities flourished in the Champlain Valley and farther south.

Plattsburgh was home to a large community of expatriates in the early 1840s. We have evidence of Canadiens enrolling to fight in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) throughout New York State. Industrial development in Keeseville on the eve of the Civil War had a magnetic effect. Agriculture, the lumber trade, and local commerce employed most French-Canadian families in the northern counties. But, as in New England, industrialization and new forms of capitalization gave birth to gigantic mill cities that would be particularly reliant on immigrant labor. Troy, on the Hudson River, became a major iron- and steel-producing center. Nearby Cohoes was home to Harmony Mills, one of the largest textile manufacturing establishments in the country.

Considering the amount of qualitative informative about French Canadians in New York State, widely accessible through public archives and newspaper databases, this post could really be a 400-page monograph. For now, let’s look more intently at the numbers.

American census returns did not include places of birth until 1850. Estimates of the French-Canadian population in 1840 aren’t far from guesswork, since researchers must rely on names that might have been anglicized or misinterpreted by enumerators. Are Charles and Adelia King actually Charles and Odélie Roy—or just a Yankee couple descended from late seventeenth-century English immigrants? This methodological challenge suggests that we may just as well rely on the estimates provided by contemporary observers than on flawed and misleading census data.

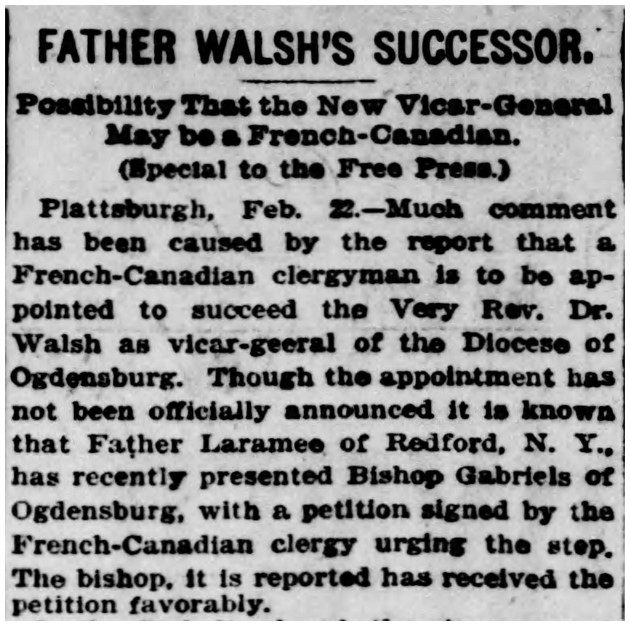

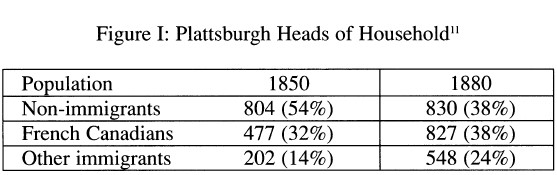

Few scholars have explored New York census data from 1850 in a systematic way, and that remains an area for further exploration. We do, however, have an insightful snapshot of Plattsburgh from 1850 to the end of the nineteenth century, which comes from historian Susan Ouellette. In an article in New York History (2002), Ouellette highlighted the sheer numerical significance of French Canadians. At century’s end, they were on their way to becoming the dominant ethnic group in the Town of Plattsburgh (not to be confused with the Village, which would soon become the City of Plattsburgh).

Ouellette also studied occupational categories and opportunities for social mobility during that time; her article stands out as a model for researchers aiming to study the economic fate of Franco-Americans in northern New York communities.

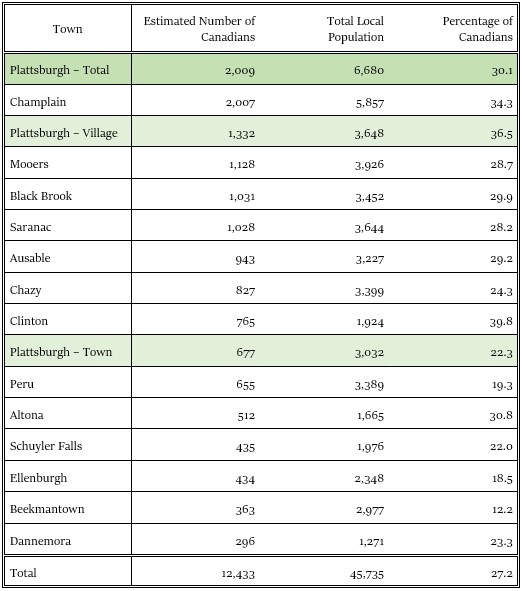

My own research brought me to the census returns of 1860, as railways opened new migration fields and communities became increasingly rooted, permanent. Town by town, in Clinton and Franklin counties, I traced Canadian settlement by forming a data set based on 25 percent of the total local population gathered through systematic sampling. I counted all people born in Canada as well as American-born children when both of their parents were natives of Canada, for they would have grown up with the language, faith, and customs of their not-so-distant homeland.

To be clear, enumerators asked about places of birth, not ethnicity. Not all people born in Lower Canada were French Canadians. I am nevertheless confident, from a close reading of given names and surnames, that in Clinton County, 90 percent of all people born north of the border were in fact French Canadians. Farther west, in Franklin County, that proportion was no doubt lower. We can still expect that at least two-thirds of Canadians in that county—maybe significantly more—were of French descent. (We must remember that English Canadians were also “on the move” in this era, and the sample does capture Canadian-born children whose parents were, for instance, Irish immigrants.)

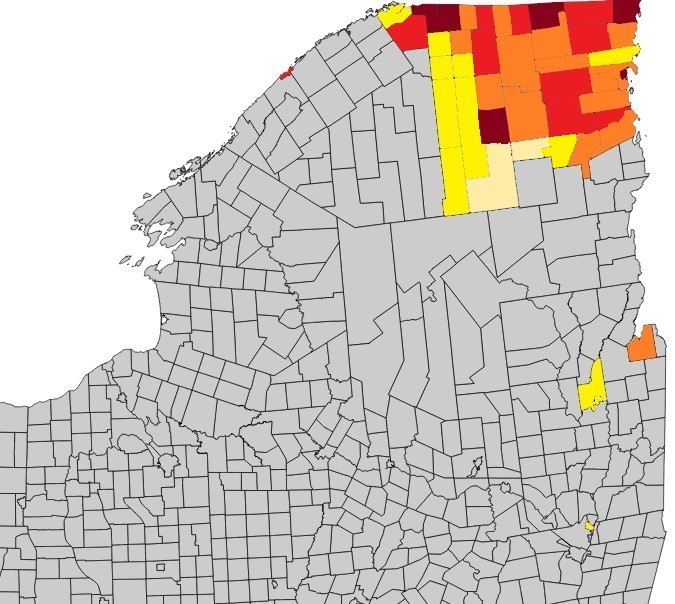

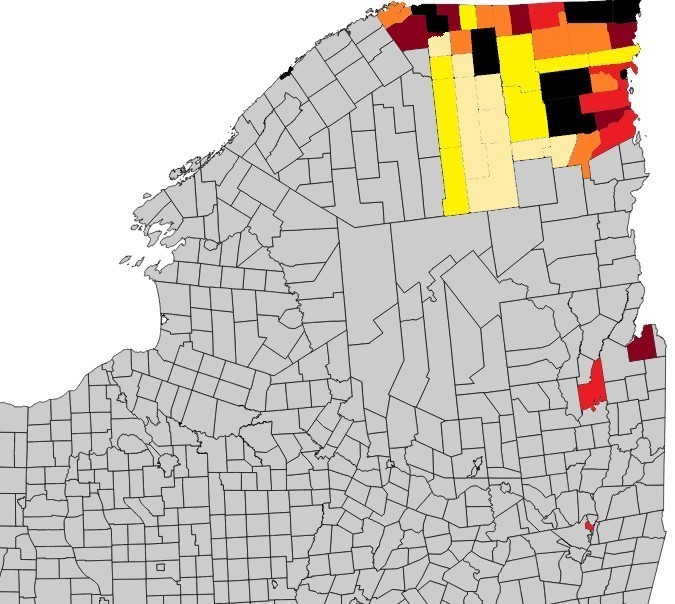

The resulting numbers are, quite simply, remarkable. Even before the Civil War, before French-Canadian national parishes had popped up in Woonsocket, Fall River, Lowell, Manchester, and Lewiston, more than a quarter of Clinton County’s population could be considered Canadian. Plattsburgh and Champlain each had more than 2,000 Canadian residents. The number for Champlain was likely higher, in fact, as this was an old area of settlement with second- and third-generation French Canadians who maintained their culture, but who would not have appeared as anything but Americans in census records. In many communities, the Canadiens formed approximately 30 percent of the local population. This situation was closely mirrored in Franklin County, with Malone’s figures being a close match for Plattsburgh’s.

Figures for Clinton County (1860)

Continued migration, large families, and the westward flow of Anglo-Americans would have raised those numbers (and proportions) in subsequent decades.

In 1860, pockets of French-Canadian population became smaller and sparser as one travelled away from Clinton and Franklin counties. Ogdensburg, located on the upper St. Lawrence River, near the Canada–U.S. border, had a Canadian population of about 2,000, and 41 percent of those residents had unmistakable French names. In Whitehall, a key point of conveyance at the southern tip of Lake Champlain, only 17 percent of residents were Canadian—but that proportion still amounted to more than 800 people. There were almost as many in Queensbury, which held the growing hamlet of Glens Falls. Approximately 40 miles south of Glens Falls, also on the Hudson River, lay Cohoes, whose Canadian population already amounted to 628.

The official report on the U.S. Census of 1860 provided aggregate data on foreign nativity for “major cities” only. In New York State, there were eight such cities: New York, Brooklyn, Buffalo, Albany, Rochester, Troy, Syracuse, and Utica. Those eight cities combined were home to more than 11,600 people born in British North America. (Note that this official figure does not include children born in the U.S. to two Canadian parents.) New York City no doubt had a population of Maritimers and, due to their economic ties and location, a number of these cities would have been home to more English Canadians (including people of Scottish and Irish descent) than French Canadians. But these areas too need to be better situated in the story of French migrations from the St. Lawrence River valley.

Official statistics from 1900 (when migration dropped significantly) and 1930 (when the great hemorrhage, as conventionally understood, ended) also help us understand the geographic concentration of French Canadians in New York State, thus highlighting areas where special study is required. Census returns for these years did distinguish French Canadians from their English counterparts. In the northern part of the state, in 1900, 9,329 French-heritage people born in Canada were divided almost equally between the counties of St. Lawrence, Franklin, and Clinton. That figure dropped to 6,459 by 1930, a sign that immigration was in fact slowing. But this is not to say that the population of self-identified French Canadians was not growing. Families preserved their culture and their heritage even as they became entirely American-born.

In 1930, there were more than 5,000 French Canadians (Canadian-born or first-generation American) in each of those rural counties. Outside of the New York metropolitan area, the only other county posting similar figures in 1930 was Albany, where Cohoes, the city of Albany, and West Troy are located. With some exceptions—for instance, Keeseville declined as an industrial center while Ticonderoga’s French population grew—the main destinations of 1860 were the principal French-Canadian communities of 1930.

Let’s still remember that French Canadians were partout, and we may not fully understand the diaspora until we take a serious look at the 1,600 French-Canadian immigrants who were living in Jefferson County, which faces Lake Ontario, in 1900. Farther south, in Oneida and Onondaga counties, the immigrant population grew from 1900 to 1930. That requires study—and some explanation. And then there’s New York City, site of one of the earliest sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste in the United States, a city that had its own French national parish and that was heavily trafficked by French Canadians as early as the California gold rush of the 1840s.

In closing, we should remember that numbers aren’t everything. It is easy to dismiss New York Franco-Americans—long quarantined from the standard Franco narrative—by suggesting that New England urban communities were, as a whole, bigger. But, by that logic, we shouldn’t study Franco-Americans at all, focusing instead on the Irish and German immigrants who were, in fact, more numerous in the United States. Statistical analysis can, however, help focus our investigation, and in few places does that inquiry need to be more fully fleshed out than in New York.

what an interesting read! I have also taken an interest in the Franco American community of New York State. I always found it weird how French ancestry is often overlooked, intentional or otherwise. There are nearly 1 million people of French descent in the state, according to some sites I have visited. I have heard that Albany alone is home to about 36,000 French Americans. Furthermore, I suspect a number of self proclaimed Irish, Italian etc. Americans have some French ancestry as well. In NYC, The French attended some of the same churches as the Italians, Irish and Germans. According to a 2006-08 American community survey, French was one of the top 10 ancestries among white Americans in NYC (at #8). As you have stated, many are just unaware of the significant French heritage the state possesses. Please keep up the great work. Looking forward to more!

Thank you for reading, Hank! I appreciate your interest. I’m really hoping we can get more people interested in this fascinating story! I for one will certainly keep at it.

You are spiking my interest with this latest post. Yes, I agree French speaking Canadians were fewer in Whitehall than up in Clinton County. Whitehall was a cross road (an aqua trail) in the heart of Yankee farmland – Washington County. This county was/is more New England than Boston! Fort Ann was initially called Westfield and settled by British soldiers. With other towns named Argyle, Cambridge, Salem, Kingsbury, Hartford all settled with military grants or the Hampshire grants, papists were not too eager to declare themselves. I suspect in 1850, French speaking canalers and farmers tried to assimilated hard and fast by Anglicizing their names, marrying Yankee women and speaking English as quickly as they could.

Thank you for this. We need to continue our efforts to inform and educate people about the FC presence in NYS. I’ve attended NYS History conferences and have asked all the book dealers present if they have books on the French in NYS. It’ s as if we never existed in NYS!!! We were here and we still are!!

Merci for this post! Ever since I began researching my French Canadian roots in earnest, coming across information about Upstate New York has been few and far between. Now, I love New England, but my roots are lumber mills on the Au Sable River, not textile mills in Lowell or Chicopee.

The Green Mountains are not the tallest in the world, but they do seem to mark a kind of cultural divide. To the east you get the more “typical” experience: the mill towns of the Connecticut, Blackstone and Merrimack Valleys, with Francos segregated into Little Canadas and practicing La Survivance amid ethnic conflict with les Bostonnais, Irish and Italians. On the west, Champlain Valley side, there were fewer tensions with other Catholics (although they certainly existed), assimilation was more rapid (people like Tim Beaulieu were being taught in French as late as the 1980s, while my great-grandparents, born about a century earlier, abandoned the language). There were also more job opportunities — there were FC farmers and foremen; my great-grandfather managed a grocery store, one of his brothers sold insurance). One of the big things is that we always called ourselves French Canadians in my family, I never came across the term Franco-American until recently. Another, smaller thing, is that the New Englanders say “tortiere”, but we’ve always said “touquire”.

Thanks for reading and commenting, Matthew! Yes, hopefully this can inspire more interest in lesser-known French-Canadian destinations and communities. Great point about the Green Mountains! They do seem like a symbolic barrier. I’d love to see more research on Plattsburgh, Keeseville, Whitehall, etc. I don’t know a whole lot of people willing to take that on, but I hope to help push the conversation forward. As you say, there are so many regional particularities worth exploring!