Franco-American political candidates do not earn the same easy acclaim from their own heritage community they once did. This is especially clear in Maine, where Paul LePage seeks to return to the governor’s office. By virtue of his policies and his remarks on his ethnic background, LePage has alienated many compatriots. His opponent, by contrast, has intentionally engaged with Franco-Americans through their cultural institutions.

There are other factors. The Franco-American presence in mainstream U.S. politics has become mundane; there are few breakthroughs still to be made. We should add that Franco-Americans are as a whole so acculturated in social terms that their voting patterns often do not differ from those of their larger civic communities, nor—as we see in Maine—do they vote for candidates simply because of shared ethnic heritage.

The current election cycle provides an opportunity to turn the clocks back to a time when every Franco-American nomination for public office was newsworthy and when Franco political behavior was closely scrutinized. Never was that more common than in the late nineteenth century, as people of French-Canadian descent became citizens and began to take part in electoral politics. Le National, the Plattsburgh newspaper owned by Benjamin Lenthier and edited by Georges Lemay, provides a valuable glimpse of this watershed moment in Franco-American history.

In 1888, like other French-language papers, Le National reflected and nourished Franco interest in the presidential election campaign and state and local races. It sought to educate new voters; it also aimed to shape their partisan preferences. Lenthier was a devoted Democrat and, through the fall of 1888, Le National was put in service of the same cause.

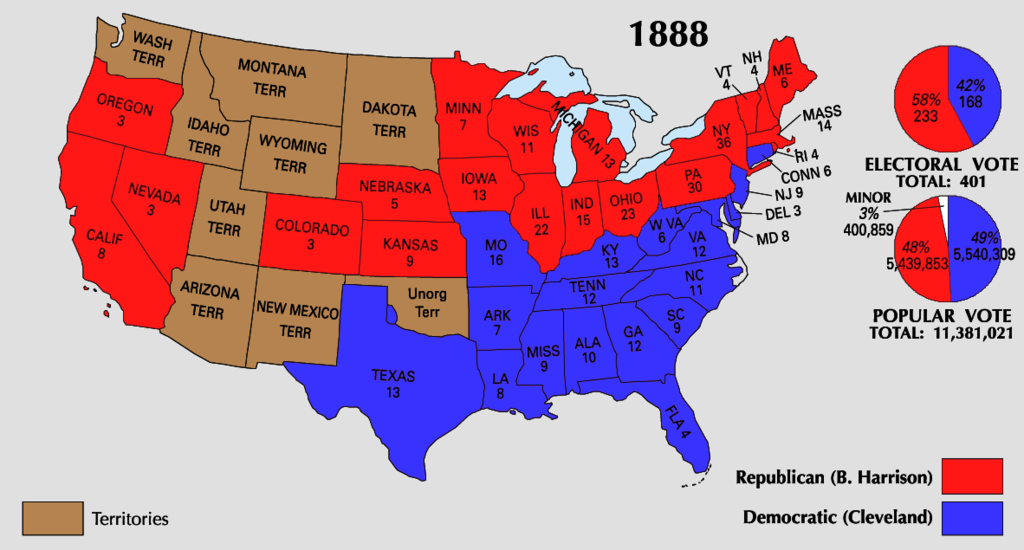

Available on Google News Archive, Le National provides a glimpse of the intense political coverage available to Franco-Americans from an early date. Though we would never know it from some of the books on the topic, ethnic newspapers were deeply interested in mainstream U.S. politics. It is also particularly important to get the view from Plattsburgh and its French Quarter, the organized Franco-American world by no means being confined to the New England states. In fact, the newspaper was likely quite correct in claiming, in 1888, that Clinton County, New York, had the highest number of Franco voters of any U.S. county. That the presidential election was likely to be determined by New York’s Electoral College votes only adds to the significance of this region.

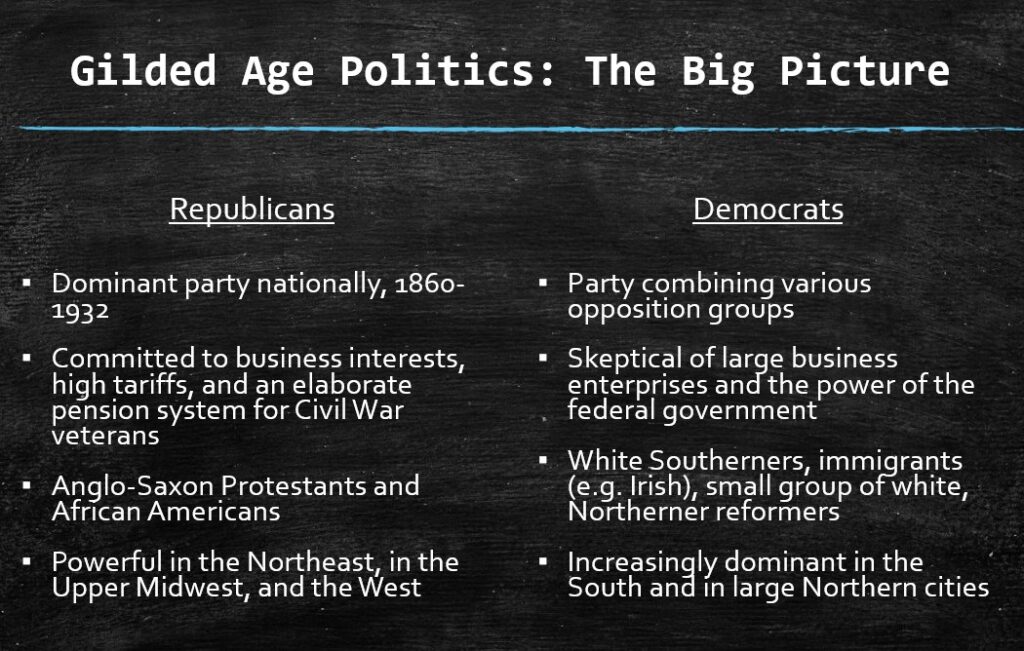

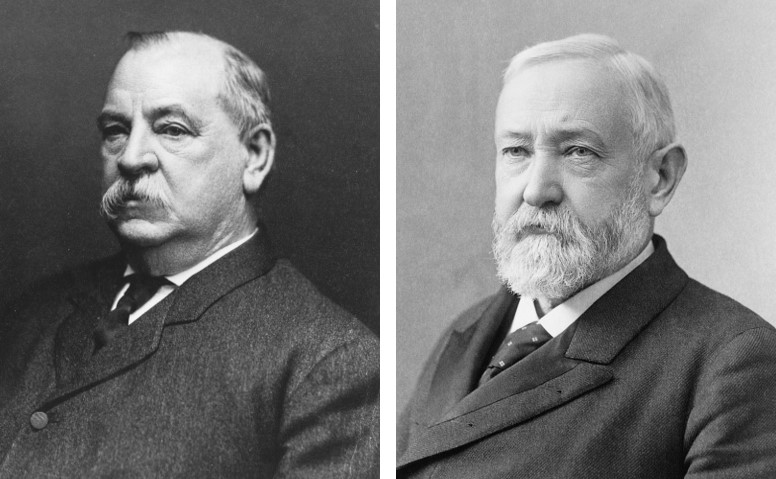

The country had witnessed a series of closely disputed national elections since 1876. In 1888, Democrat Grover Cleveland of New York, president since 1885, whom Le National supported, was facing a challenge from Republican Benjamin Harrison, a former Indiana senator. That being said, party nominees had little effect on voters’ choice in this era. Allegiances were typically a product of built-in regional, ethnic, and class-based identities and interests. Political activity was organized locally and was by its very nature participatory and demonstrative—as the persistence of torchlight parades made plain. Entertainment was part of the experience: voters often attended the rallies of the rival party to hear charismatic speakers and taste the pageantry.

In the midst of all of this—and perhaps because of a desire to be similarly involved—the naturalization movement made inroads in Franco-American communities. In the fall of 1888, Le National commented on the activities of naturalization clubs in Willimantic, Connecticut; Chicopee Falls, Lowell, Spencer, and Springfield, Massachusetts; and Biddeford, Maine. Those activities still did not quite meet the hopes of organizers. In Spencer, Canadians amounted to 240 out of 1,400 local voters. Le National thought the number could and should be much higher in light of French Canadians’ share of the population. The editor nevertheless remained sanguine:

Our element continues its invasive mission. In all areas, this year, French Canadians in the United States are making breakthroughs and asserting themselves. With work and perseverance, we will easily obtain the position we seek here, and we will succeed in establishing the considerable influence we need to be respected by other races.

The great orators of the Franco-American world did not leave rallies to Anglo-Saxon and Irish Americans. They too barnstormed across the Northeast. Lenthier crossed the lake and spoke in Burlington; he canvassed across northern New York and took part in events in Keeseville, Willsboro, Malone, and Ogdensburg. Journalist Emile Tardivel came to Plattsburgh to promote the Democratic cause in October. Omer Larue of Putnam, Connecticut, traveled through Massachusetts. Dr. Louis J. Martel, the prime mover of all things Franco-American in Lewiston, addressed crowds in Albany and Cohoes on back-to-back days in mid-October; he then went to Webster, Massachusetts.

Martel’s brother-in-law, F. X. Belleau, aged not yet 30, traveled to northern New Hampshire. He spoke in favor of the party of “Jefferson, Jackson, and Cleveland” in Lancaster and, the next day, in Littleton, home of 50 to 75 Franco-American voters. Four days before the election, an invitation from the local Democratic committee brought him to Laconia. Politics aside, his engaging presence led some to propose founding a société Saint-Jean-Baptiste in the central New Hampshire town.

Le National also reported on Democratic organizations in Franco-American communities in Connecticut; in Dudley, Haverhill, and Spencer, Massachusetts; and as far as Michigan and the Dakotas.

Republicans did not have the bench strength of Democrats when it came to Franco-American leaders. They did, however, have devoted spokesmen. Lenthier’s paper acknowledged Republican Hugo Dubuque of Fall River as the most prominent Franco-American since Ferdinand Gagnon’s passing two years earlier. Dubuque did his part for the GOP. He wielded considerable political influence through Fall River’s L’Indépendant. J. Misaël Authier was, like all of the aforenamed, a native of Quebec; aged 44, he happened to be the oldest. Authier edited the staunchly Republican Patrie in Cohoes. He engaged in polemics with Le National and dared to canvas in Lenthier’s backyard—Clinton County—though he declined to debate Lenthier when challenged to do so. In short, Franco-America’s earliest pantheon—including Freddie Gagnon—was far from apolitical and by no means immune to the deep divisions experienced by other ethnic groups.

The pages of Le National suggest these divisions occurred over a handful of issues at most. The first major debate between Democratic and Republican outlets as summer turned to fall revolved around the Riel affair. Three years earlier, Louis Riel had hanged for his part in the North-West Resistance. We often forget that Riel had become an American citizen—but that convenient fact did not escape the attention of Franco-American Republicans. They attacked the Cleveland Administration and Democrats as a whole for failing to intervene to save the life of an American citizen accused of a crime north of the border. This prove to be an enduring quarrel between Le National and L’Indépendant, revealing along the way that involvement in U.S. politics did not rule out attachment to a transnational French-Canadian identity.

Identity was again at the fore as Republicans courted Franco-Americans by accusing President Cleveland of anti-Catholic views. This charge notably stemmed from a veto he had applied to a bill supporting a Catholic institution while he was governor of New York. At the end of September, after a long digression on its desire to keep religion out of the campaign—the high road it now had to abandon—Le National responded to this attack. It quoted the bishop of Albany on Cleveland’s broad, tolerant feelings. It also cited the credits for Catholic-run residential schools for Indigenous nations voted under Cleveland’s administration.

Approval of this evangelizing and “civilizing” work among Native Americans is, in retrospect, a regrettable chapter that points to the very different fates awaiting people of French descent and Indigenous groups. The campaign also highlighted Franco-American editors’ view of other ethnicities. Lenthier came out in favor of Chinese exclusion. Economic concern drove a Franco-American nativism. Reacting to Pierre Primeau’s nomination for county offices in Michigan, Le National delivered an unsolicited comment on other “races”:

It’s a known fact today that Republicans have always shown themselves hostile to the arrival of intelligent foreign races in America. They have disapproved of Canadians and drawn them into the same hatred they hold for Irish Catholics. Meanwhile, they import Chinese, Italians, Bohemians, and a multitude of hordes dressed in rags that come and offer disastrous competition for our workers.

Both parties claimed to be serving the best interests of workers. This played out in long treatises on tariffs. Republicans argued that high duties on imported products helped protect manufacturing jobs. Democrats replied that high tariffs added significantly to the cost of living. Forced to defend themselves, Le National and Worcester’s Le Travailleur denied supporting free trade; they demanded tariff reform. While in Albany, Martel condemned Andrew Carnegie—a friend of Republican leader James G. Blaine—whose labor practices had lately driven his legions of employees to strike. Although not a dominant theme of the campaign, some Democratic spokesmen were willing to play on class differences and class interests. After the election, they declared that employers had coerced voters by appending GOP handbills to their paychecks.

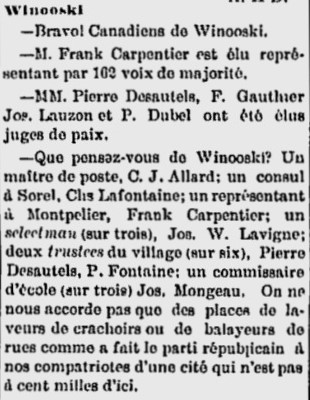

Finally came the issue of ethnic recognition: which party offered the most positions and nominations to people of French-Canadian descent and recognized their interests? Lenthier and others engaged in a numbers game that would endure for decades. The Democratic administration had apparently outdone the GOP in Franco-American appointments—so said Le National. Edmond Mallet had been named to the Indian Department, two compatriots served as consuls in Quebec, and Dr. J. H. Larocque was an examiner of government pensioners in northern New York. Two French Canadians served as instructors for the “sauvages” in the West. There were, in fact, hundreds of men of French-Canadian background serving in lucrative government capacities, many of them as postal agents and postmasters. What’s more, Cleveland had welcomed a Franco-American committee bearing an invitation to the Franco-American convention in Nashua earlier in the year. But Republicans had their own figures and they served the very same purpose. Bread and butter issues might matter; so did symbolic recognition of an ethnic group that was still carving its place on U.S. soil.

All of these issues mattered, but there was no escaping the vicious tone of the campaign, even among Franco-Americans. It is difficult to square the apparent collegiality and celebrations of the Nashua “national” convention in June 1888 with the blistering attacks between compatriots as the country moved closer to election day. For instance, Le Travailleur went for the jugular in a piece titled “Dubuque vs Dubuque” in September. The Fall River orator had penned pieces for Le Travailleur at the turned of the 1880s—when both the paper and the columnist endorsed Democratic ideas. Dubuque was depicted as a flip-flopper whose loyalty the Republican Party had bought. Neither party had a monopoly on this type of language.

In the end, Grover Cleveland won the popular vote at the national level. Le National was quick to highlight the strong support he received not only from Southern states, but from some of the largest Northern cities as well. The Electoral College had its own verdict. Only Indiana and New York switched columns from the prior presidential election, but they were enough to put Benjamin Harrison over the top, ending the first elected Democratic administration since the antebellum era. In Clinton County, the supposedly Democratically-inclined Franco-American population could not prevent a Harrison majority. Le National broke down the reasons for Democratic losses—including, not without bitterness, GOP money and Democratic divisions. A gracious statement nonetheless bookended the hard-fought campaign:

As for us, we have fulfilled our journalistic duty. We fought strenuously for a cause we believe to be sacred. We have waged a war of principles, a loyal war that we may be proud of. We accept in a good faith an outcome we did not wish for. With fate turning against us, we respectfully salute he who is no longer the mere representative of a party, but the president of a great nation. We hope that like Mr. Cleveland he will rise above party considerations and secure for our republic the respect of foreign powers.

A correspondent signing “Un Patriote” invited community members to recall the resolutions and the spirit of the Nashua convention and the extensive work still to be accomplished.

Overall, the election result bore out the deep partisan fracture among Franco-Americans. Of the state legislators elected in New England in November, seven were Democrats and six, Republicans. Regardless, Franco-Americans could celebrate their growing political presence. Dr. Larocque, a friend of Lenthier, appeared on the Clinton County ballot, though he failed in his bid to become coroner. Four men were elected to the Maine legislature in September: one from Lewiston, another from Biddeford, and two from the St. John Valley. Ogdensburg had Franco-American aldermen and town supervisors. Edouard Marier of Lawrence, Massachusetts, served in public office. In addition, Le National carried biographies of Jovite Pinard, a municipal councilor and then a justice of the peace in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, and Dr. Louis L. Auger, the municipal physician in Great Falls (later Somersworth), New Hampshire. Still in New Hampshire, Nashua elected four Franco-Americans as aldermen or councilors and sent one compatriot to the state legislature.

In subsequent years, Lenthier sought to avenge this loss. He moved his newspaper to Lowell and consolidated a media empire in New England ahead of the 1892 election. Both he and F. X. Belleau were sent to Quebec as consuls when Cleveland returned to office in 1893. Martel made the first of two mayoral runs in Lewiston also in 1893. Dubuque’s reputation grew due to his continued devotion to the French-Canadian “national” cause. Survivance still permeated Franco-American life in large centers but, after the Nashua event, Franco leaders would not come together again in convention for five years. They met in Chicago in 1893.

The story of Franco-American engagement in mainstream U.S. politics is still little-known; it requires further elucidation beyond my blog, my book, and the few other works on the subject that are readily available. One aspect that will require much more attention is the part played by women and the extent to which they could voice their interests politically even in the absence of the right to vote. We know that elites appealed to them during naturalization campaigns; they were expected to persuade their husbands and sons to seek American citizenship. Some were particularly well-situated as spectators but also as likely participants in political discussions. Hugo Dubuque’s wife Annie, for instance, also happened to be sister to a Democratic mayor of Fall River.

The late Gilded Age and the Progressive Era witnessed female mobilization in social causes that culminated in their right to vote at the federal level. These crusades were, however, predominantly the province of middle-class Protestant women. In Franco-America, women’s social engagement continued to occur within their own cultural and denominational world. Still, we should not work from the premise that Franco women were political non-entities. There are many stories yet to be explored or captured. L’invitation est lancée.

For more on Franco-American political involvement, check out the following posts:

- The Hero They Needed: Edmond Mallet

- Why Was Major Mallet Fired?

- Franco Pioneer Russell Niquette

- Franco-American Women as Political Actors, 1890-1920

- Joseph Denonville Bachand: French Vermonter and Statesman

- Chalifoux, Part II: The Franco-American Who Won Boston

- Franco-Americans as Political Actors

And in French:

For the bigger story, be sure to check out my “Tout nous serait possible”: Une histoire politique des Franco-Américains, 1874-1945, available from the Presses de l’Université Laval.

Thank you for providing the graphic indicating the differences among the two parties during these times. Rather than trying to read this with a modern-day lens, this graphic allows everything to make more sense. This has rekindled my interest in learning about the Franco-American experience and its effect. If only there was more time during the day!