Part I: Welcoming the Victor

The American conqueror stopped to look up and down the St. Lawrence, then went on to survey the area surrounding Quebec City. The figure was neither a colonial officer accompanying James Wolfe in 1759, nor one of Richard Montgomery’s men at the dawn of the American Revolution. The conqueror was none other than Ulysses S. Grant and the year was 1865.

This is not counterfactual history—though, of course, Grant had defeated the Confederate States of America, not a British colony. Only four months after the end of the U.S. Civil War, the triumphant general traveled across the northern states with his wife, children, and military staff. He did not stop there. With officials of the Grand Trunk railway facilitating his movements, thanks to a specially chartered train, Grant crossed into foreign territory. After a series of Anglo-American controversies through the war, government leaders and observers on both sides of the boundary line had ample reason to be apprehensive.

Anglo-American relations had brightened considerably in the 1850s. Steamboats, canals, and rail lines accelerated the exchange of goods and people between the British colonies and the United States. Thousands of ordinary Canadians found work south of the border. Commerce grew exponentially, with the new technologies providing a tangible axis for the limited free trade agreement signed in 1854. Telegraphy increased communication and a common cultural world developed, but not simply through newspapers. In the early 1850s, Canada welcomed in quick succession Orestes Brownson, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

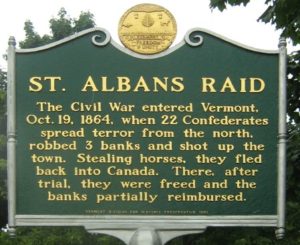

That era of international good feeling ended with hardly veiled expressions of support for the Confederacy among high-ranking British officials. In 1861, the commander of the Union’s Trent seized two Confederate diplomats from a British merchant ship. The seceding states operated the Alabama, a British-built ship with which they sank numerous Union vessels before its own 1864 demise. At last, in the fall of 1864—less than ten months before Grant’s visit—supporters of the Confederacy launched from Canadian soil a daring raid on banks in St. Albans, Vermont. Judicial authorities in Montreal released the agents before they could be extradited.

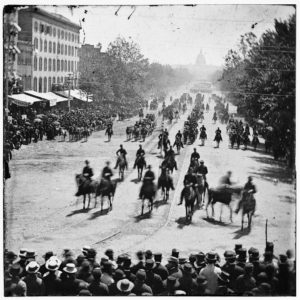

Alongside ministerial instability and fiscal challenges, incidents such as these added urgency to the pursuit of a new partnership between the North American colonies—to which the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences of 1864 attest. The end of the war in the spring of 1865 did little to reassure Canadians. With the seceding states “tamed,” the Union might now look to settle scores on its northern border. In May, a two-day grand review of victorious forces in Washington, D.C., illustrated the magnitude of the threat.

As commanding general of the Union armies, Ulysses S. Grant manifested little interest in a hypothetical invasion of Canada. He had much to tend to, the laurels of peace weighing on him almost as heavily as the sword of war. Evidence suggests that he too had been targeted for assassination on April 14, 1865, and an unidentified man would seek to injure him in New York City and again in Boston that summer. It took time and effort to reign in Confederate troops in Texas and the West—a major Confederate force beyond the Mississippi only surrendered after the grand review in Washington—and the defeated states required a sustained military presence.

Still, Grant, a national hero, could afford some leisure. Accompanied by his family and a retinue of American colonels, he visited Portland, Maine, on August 4 and 5. It would seem that earlier plans had him going to Halifax to repay a visit by Major General Charles Hastings Doyle, one of the senior officers in British America. Ultimately, they would meet in Quebec City. From Portland, Grant traveled across Maine and northern New Hampshire by rail. A joyous crowd welcomed him in Island Pond, Vermont, where he lunched. Several hours later, he was in Canada East. In Sherbrooke and Richmond, city leaders acknowledged the general’s presence with formal addresses. By the end of the day, on August 5, Grant was in Quebec City, where a somber mood was perhaps lingering among elites. The venerable Prime Minister Etienne-Paschal Taché had died on July 30 and was honored with a state funeral less than three days before Grant’s arrival.

The general checked in at the Hôtel Saint-Louis, located on Saint-Louis Street at the corner of Haldimand. The establishment was perhaps Quebec City’s finest and had in fact hosted many of the delegates to the conference held in October 1864. That evening, the governor general, Viscount Monck, received Grant at his official residence, located at the far end of the Plains of Abraham. If tensions still ran high between Britain and the United States, there was ample room for dialogue. The officers in Quebec City were undoubtedly deeply interested in the strategic aspect of the Union victory. At the same time, military and political status bound Grant’s party and its Canadian hosts. The following day, after attending a Sunday service, the general was led on a tour of the Quebec area. General Doyle, who had planned nearly a week’s worth of activities for Grant, must have been disappointed to learn that his guest’s time in the city was to be much shorter.

On Monday, August 7, the Union commander boarded a steamship to Montreal. The good will was such that Monck was present to see him off and bid him happy travels. The next day, Grant met with Grand Trunk management and visited the Victoria Bridge. He also stopped at St. Lawrence Hall, a luxurious hotel that had welcome a number of Confederate sympathizers during the Civil War, not least among them John Wilkes Booth. Dozens of Montreal’s leading citizens called on Grant—militia officers, politicians, judges, a bishop of Montreal (likely Francis Fulford, the Anglican prelate), as well as a novelist, Georges Boucher the Boucherville.

We can imagine that Grant’s trip was far from leisurely, despite the presence of his family. While tending to correspondence, he maintained a dizzying pace. He spent no more than a day in Montreal before setting off to Niagara Falls. He would then visit Buffalo, travel across Canada West to Detroit. In September, Grant returned to Galena, Illinois, where he had resided before the war, and finally visited President Lincoln’s temporary resting place in Springfield.

On the surface, as Grant’s time in Canada ended, his trip could be deemed a diplomatic success. But already controversy was brewing. It appeared that the United States might, before long, be at war again.

Read Part II next week.

Pingback: Teaching Canada–U.S. Relations in 2020 – Active History