As previously noted on this blog, the concept of américanité is as relevant to Canadians who never left their native land as it is to Franco-Americans and other expatriates. The influence of American institutions, values, and economic development has been constant north of the boundary line now for more than two centuries. Present-day scholars recognize that a certain Americanness has permeated the intellectual and material culture of French Canada for much of that period. To nineteenth-century American observers, however, this Americanness was not a matter of degree—it was an unambiguous standard of progress and freedom that French Canadians failed to meet.

Researchers in the field of Franco-American studies recognize that immigrants faced nativist pressures and marginalization in the United States. Granted, French Canadians enjoyed the privilege of “whiteness” that other migrant groups, even some from Europe, did not, and as a result the former were spared the worst of American xenophobia. Still, in their daily lives and in the press, these immigrants were deemed backward, unsophisticated, hostile to democratic-republican values, incapable of integrating if not unwilling to do so, etc.

The mass migration of French Canadians in the last three decades of the nineteenth century nourished the apprehension of “old-stock” Americans. Suddenly, the loss of their own American culture seemed likely, overwhelmed by groups perceived to be inferior. “Scientific” racism helped various strands of xenophobic sentiment to coalesce, brought intellectual credibility to the rejection of pluralism, and eventually formed the basis of anti-immigrant legislation.

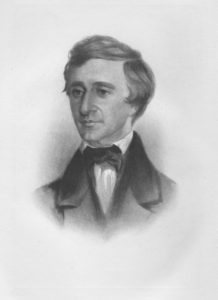

When one American observer—Henry David Thoreau—set foot on Canadian soil in 1850, all of this still belonged to the future. Certainly, by then, French Canadians had begun to seek new opportunities in the United States; Thoreau had met one of them, Alexandre Therrien, near Walden in 1845. But there was little to suggest at this point that hundreds of thousands of Canadiens would settle permanently south of the border, little to indicate that American culture was meaningfully threatened.

Thus, Thoreau’s account of his northern excursion, titled A Yankee in Canada, provides interesting perspective on the extent to which French Canadians could be American, migration being left out of the equation.

Often overlooked by Thoreau scholars, A Yankee in Canada helps to shed light on the author’s vision of the United States, thanks to the contrast of a foreign land. More significantly, it enables those working on French Canada to better situate the roots of American contempt as well as the meaning of l’américanité. Ultimately, in Thoreau, we find no hint of racial essentialism. Freed from despotic institutions (the Roman Catholic Church, the British colonial regime), French Canadians could indeed enjoy the promise of the United States’ founding ideals. A full-length study on the subject is available at the American Review of Canadian Studies.

definitive version appeared in 1866 (Archive.org)

A shorter treatment appears on Beyond Borders: The New Canadian History, the blog of the Wilson Institute:

It was a paradox of the age that, as national boundaries hardened and central state authority grew from the late 1830s to the 1850s, continental integration accelerated. The advent of the railway era and the expansion of telegraph lines increased cross-border encounters between British North America and the United States. These technologies created novel economic opportunities, facilitated expatriation, and forced intercultural exchanges on an entirely new scale.

Enter Henry David Thoreau, the Massachusetts writer who famously went to Walden. In his native Concord and beyond, Thoreau was a first-hand witness to these sweeping technological changes. If he lamented the material concerns of the age, he did not forsake all that these changes wrought. In August 1850, Thoreau boarded a train bound for Canada. His nine-day excursion with friend Ellery Channing, Thoreau’s only trip outside of the United States, exposed the possibilities and misunderstandings attendant to increasingly sustained contact between vastly different cultures. Continue reading.

Leave a Reply